Category: Recommended Reading

Pasolini on Caravaggio’s Artificial Light

Pier Paolo Pasolini at The Paris Review:

Anything I could ever know about Caravaggio derives from what Roberto Longhi had to say about him. Yes, Caravaggio was a great inventor, and thus a great realist. But what did Caravaggio invent? In answering this rhetorical question, I cannot help but stick to Longhi’s example. First, Caravaggio invented a new world that, to invoke the language of cinematography, one might call profilmic. By this I mean everything that appears in front of the camera. Caravaggio invented an entire world to place in front of his studio’s easel: new kinds of people (in both a social and characterological sense), new kinds of objects, and new kinds of landscapes. Second: Caravaggio invented a new kind of light. He replaced the universal, platonic light of the Renaissance with a quotidian and dramatic one. Caravaggio invented both this new kind of light and new kinds of people and things because he had seen them in reality. He realized that there were individuals around him who had never appeared in the great altarpieces and frescoes, individuals who had been marginalized by the cultural ideology of the previous two centuries. And there were hours of the day—transient, yet unequivocal in their lighting—which had never been reproduced, and which were pushed so far from habit and use that they had become scandalous, and therefore repressed. So repressed, in fact, that painters (and people in general) probably didn’t see them at all until Caravaggio.

Anything I could ever know about Caravaggio derives from what Roberto Longhi had to say about him. Yes, Caravaggio was a great inventor, and thus a great realist. But what did Caravaggio invent? In answering this rhetorical question, I cannot help but stick to Longhi’s example. First, Caravaggio invented a new world that, to invoke the language of cinematography, one might call profilmic. By this I mean everything that appears in front of the camera. Caravaggio invented an entire world to place in front of his studio’s easel: new kinds of people (in both a social and characterological sense), new kinds of objects, and new kinds of landscapes. Second: Caravaggio invented a new kind of light. He replaced the universal, platonic light of the Renaissance with a quotidian and dramatic one. Caravaggio invented both this new kind of light and new kinds of people and things because he had seen them in reality. He realized that there were individuals around him who had never appeared in the great altarpieces and frescoes, individuals who had been marginalized by the cultural ideology of the previous two centuries. And there were hours of the day—transient, yet unequivocal in their lighting—which had never been reproduced, and which were pushed so far from habit and use that they had become scandalous, and therefore repressed. So repressed, in fact, that painters (and people in general) probably didn’t see them at all until Caravaggio.

more here.

Thunderclap: A Memoir of Art & Life & Sudden Death

Norma Clarke at Literary Review:

‘We see pictures in time and place … They are fragments of our lives, moments of existence that may be as unremarkable as rain or as startling as a clap of thunder,’ Cumming writes. A love of Dutch art and a passion for looking at pictures were bequeathed to Cumming by her artist parents. She wrote about her mother’s fragmented, mysterious early life in On Chapel Sands (2019). In Thunderclap it is Laura’s father, James Cumming, who takes centre stage, and like On Chapel Sands the book is infused with love – of parents, childhood, pictures and words. It is at once deeply personal and inclusive, because it is about the shared experience of looking at pictures and the shared desire to know and understand what these ‘moments of existence’ mean. I liked reading Thunderclap so much that I immediately reread On Chapel Sands. Together, these books are a remarkable experiment in form as well as a richly satisfying extended meditation on art, life and death.

‘We see pictures in time and place … They are fragments of our lives, moments of existence that may be as unremarkable as rain or as startling as a clap of thunder,’ Cumming writes. A love of Dutch art and a passion for looking at pictures were bequeathed to Cumming by her artist parents. She wrote about her mother’s fragmented, mysterious early life in On Chapel Sands (2019). In Thunderclap it is Laura’s father, James Cumming, who takes centre stage, and like On Chapel Sands the book is infused with love – of parents, childhood, pictures and words. It is at once deeply personal and inclusive, because it is about the shared experience of looking at pictures and the shared desire to know and understand what these ‘moments of existence’ mean. I liked reading Thunderclap so much that I immediately reread On Chapel Sands. Together, these books are a remarkable experiment in form as well as a richly satisfying extended meditation on art, life and death.

more here.

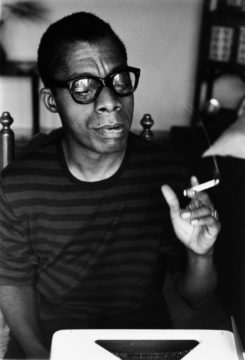

James Baldwin in Turkey

Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi in The Yale Review:

The eleven-minute black and white documentary, James Baldwin: From Another Place, directed by Sedat Pakay and filmed in Istanbul in May 1970, opens with a shot of Baldwin lying supine in a large bed in a sparsely decorated room. The curtains are closed. Baldwin throws back the covers and gets up; he is wearing nothing but a pair of white briefs. He turns his back to the camera and opens the curtains. A sharp Mediterranean light floods in. Baldwin scratches the small of his back, and we hear him say in voiceover: “I suppose that many people do blame me for being out of the States as often as I am, but one can’t afford to worry about that because one does, you know, you do what you have to do the way you have to do it. And as someone who is outside of the States you realize that it’s impossible to get out, the American powers are everywhere.” The camera pans over the glittering Bosphorus Strait as American ships glide silently through the passage connecting Asia and Europe.

The eleven-minute black and white documentary, James Baldwin: From Another Place, directed by Sedat Pakay and filmed in Istanbul in May 1970, opens with a shot of Baldwin lying supine in a large bed in a sparsely decorated room. The curtains are closed. Baldwin throws back the covers and gets up; he is wearing nothing but a pair of white briefs. He turns his back to the camera and opens the curtains. A sharp Mediterranean light floods in. Baldwin scratches the small of his back, and we hear him say in voiceover: “I suppose that many people do blame me for being out of the States as often as I am, but one can’t afford to worry about that because one does, you know, you do what you have to do the way you have to do it. And as someone who is outside of the States you realize that it’s impossible to get out, the American powers are everywhere.” The camera pans over the glittering Bosphorus Strait as American ships glide silently through the passage connecting Asia and Europe.

Pakay’s film has long been almost impossible to see in the United States, aside from a short clip on YouTube. But in February, it began streaming on the Criterion Channel, and its reappearance is a useful occasion to re-examine one of the most important, and yet relatively unknown, aspects of Baldwin’s career: his time in Turkey.

More here.

An Enormous Gravity ‘Hum’ Moves Through the Universe

Jonathan O’Callaghan in Quanta:

The discovery, announced today, shows that extra-large ripples in space-time are constantly squashing and changing the shape of space. These gravitational waves are cousins to the echoes from black hole collisions first picked up by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) experiment in 2015. But whereas LIGO’s waves might vibrate a few hundred times a second, it might take years or decades for a single one of these gravitational waves to pass by at the speed of light.

The discovery, announced today, shows that extra-large ripples in space-time are constantly squashing and changing the shape of space. These gravitational waves are cousins to the echoes from black hole collisions first picked up by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) experiment in 2015. But whereas LIGO’s waves might vibrate a few hundred times a second, it might take years or decades for a single one of these gravitational waves to pass by at the speed of light.

The finding has opened a wholly new window on the universe, one that promises to reveal previously hidden phenomena such as the cosmic whirling of black holes that have the mass of billions of suns, or possibly even more exotic (and still hypothetical) celestial specters.

More here.

“Gödel, Escher, Bach” author Doug Hofstadter on the state of AI today

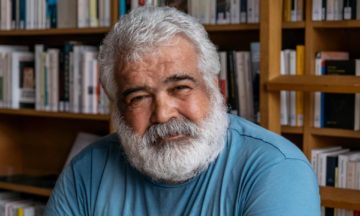

Khaled Khalifa: ‘All the places of my childhood are destroyed’

Michael Safi in The Guardian:

Khaled Khalifa is a Syrian novelist, poet and screenwriter whose work has been awarded the Naguib Mahfouz medal for literature, one of the Arab world’s highest literary honours. His soulful, often wry stories traverse time but are centred on the Syrian city of Aleppo, near where Khalifa was born in 1964, and once one of the world’s great cultural and trading hubs.

Khaled Khalifa is a Syrian novelist, poet and screenwriter whose work has been awarded the Naguib Mahfouz medal for literature, one of the Arab world’s highest literary honours. His soulful, often wry stories traverse time but are centred on the Syrian city of Aleppo, near where Khalifa was born in 1964, and once one of the world’s great cultural and trading hubs.

He studied and spent his early career in the city, but has lived in Damascus since 1999, one of the few writers who stayed throughout the country’s appalling civil war. He has tried to write about the Syrian capital, he said, but keeps finding himself drawn back to his home city. “After 50 pages, I felt it was not good writing,” he said. “I don’t know the fragrance of Damascus. So I turned back to Aleppo, and I accepted: OK, this is my place. I’ll write all my books about Aleppo. She is my city and resides deep in myself, in my soul.”

While Khalifa was writing his new book, No One Prayed Over Their Graves, Aleppo was comprehensively destroyed in fighting between the Syrian government and rebels. His work is banned in Syria.

More here.

Mughal-e-Azam: The Musical’s Prelude Screening At Times Square

People on Drugs Like Ozempic Say Their ‘Food Noise’ Has Disappeared

Dani Blum in The New York Times:

Until she started taking the weight loss drug Wegovy, Staci Klemmer’s days revolved around food. When she woke up, she plotted out what she would eat; as soon as she had lunch, she thought about dinner. After leaving work as a high school teacher in Bucks County, Pa., she would often drive to Taco Bell or McDonald’s to quell what she called a “24/7 chatter” in the back of her mind. Even when she was full, she wanted to eat. Almost immediately after Ms. Klemmer’s first dose of medication in February, she was hit with side effects: acid reflux, constipation, queasiness, fatigue. But, she said, it was like a switch flipped in her brain — the “food noise” went silent.

Until she started taking the weight loss drug Wegovy, Staci Klemmer’s days revolved around food. When she woke up, she plotted out what she would eat; as soon as she had lunch, she thought about dinner. After leaving work as a high school teacher in Bucks County, Pa., she would often drive to Taco Bell or McDonald’s to quell what she called a “24/7 chatter” in the back of her mind. Even when she was full, she wanted to eat. Almost immediately after Ms. Klemmer’s first dose of medication in February, she was hit with side effects: acid reflux, constipation, queasiness, fatigue. But, she said, it was like a switch flipped in her brain — the “food noise” went silent.

“I don’t think about tacos all the time anymore,” Ms. Klemmer, 57, said. “I don’t have cravings anymore. At all. It’s the weirdest thing.” Dr. Andrew Kraftson, a clinical associate professor at Michigan Medicine, said that over his 13 years as an obesity medicine specialist, people he treated would often say they couldn’t stop thinking about food. So when he started prescribing Wegovy and Ozempic, a diabetes medication that contains the same compound, and patients began to use the term food noise, saying it had disappeared, he knew exactly what they meant.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Reeling in a Skate on Kachemak Bay, Alaska

We drop bait and jig down eighteen fathoms,

trolling bottom for the halibut they say

are white and big as jib sails full of wind.

We drift this way all morning and I watch the men

pull up 30-pounders and sometimes

scaly Irish Lords, lustered as fool’s gold.

Drugged by the surprising warmth of this

eclipsed and argent Arctic light, I am amazed

when my line drags taut and in my hands

the heavy rod dips like a heron bends to drink.

I reel and reel, pulling up my own weight,

heavy as wet canvas. The men say to go slowly,

it will roll in fear and dive from foreign sun—

this fish has never seen the light. But who knows

what I’ve snagged from sodden sleep,

what blunt-eyed creature I haul out of darkness,

a ghostly harbinger that wavers toward me

like an insubstantial scrap of paper,

becoming larger as it nears. Too tired to resist

the last few feet it seems to help,

ascending easily, entranced by this bright world.

by Susan Elbe

—from Rattle #16, Winter 2001

Sunday, July 2, 2023

‘Why I might have done what I did’: conversations with Ireland’s most notorious murderer

Mark O’Connell in The Guardian:

Among Irish people old enough to remember the summer of 1982, Malcolm Macarthur is as close to a household name as it is possible for a murderer to be. He grew up in County Meath in the east of Ireland, on a grand estate with a housekeeper, a gardener and a governess. In his 20s, he received a large inheritance, and lived well on its bounty. But on the brink of middle age, he found he was going broke. At the time, the IRA was conducting a campaign of bank heists to fund their struggle. Macarthur was a clever and capable man, he reasoned, and so why should he not be able to pull off something along those lines?

Among Irish people old enough to remember the summer of 1982, Malcolm Macarthur is as close to a household name as it is possible for a murderer to be. He grew up in County Meath in the east of Ireland, on a grand estate with a housekeeper, a gardener and a governess. In his 20s, he received a large inheritance, and lived well on its bounty. But on the brink of middle age, he found he was going broke. At the time, the IRA was conducting a campaign of bank heists to fund their struggle. Macarthur was a clever and capable man, he reasoned, and so why should he not be able to pull off something along those lines?

He had been living for some months with a woman named Brenda Little and their son in Tenerife. He told Little that he had financial affairs to attend to, and flew to Dublin.

More here.

Most of the energy you put into a gasoline car is wasted; this is not the case for electric cars

Hannah Ritchie in Sustainability by Numbers:

For every dollar of petrol you put, you get just 20 cents’ worth of driving motion. The other 80 cents is wasted along the way – most of it as heat from the engine.

For every dollar of petrol you put, you get just 20 cents’ worth of driving motion. The other 80 cents is wasted along the way – most of it as heat from the engine.

Electric cars are much better at converting energy into motion. For every dollar of electricity you put in, you get 67 cents of driving motion plus another 22 cents of energy that’s recovered from regenerative braking. That means you get 89 cents’ worth out.

More here.

Two Ancestral Languages

Richard Dawkins at The Poetry of Reality:

The collective power endowed by language is captured in the legend of the Tower of Babel, where it threatened even God himself. “Go to,” God said, “Let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.” And lo, as a result of quasi-evolutionary divergence, we speak many thousands of mutually unintelligible tongues, the exact number undefined, mostly because dialect grades into language so we can’t decide where one language ends and the next begins. This smearing out is seen both across geographical space (think English worldwide) and through historical time as languages evolve through the centuries (try reading Chaucer). Nevertheless, because language is partly digital, chunked into the discrete semantic units that we call words, it is capable of great fidelity of transmission, especially in written forms. Yet, despite being thus capable, precious little verbal information from our dead ancestors filters down.

The collective power endowed by language is captured in the legend of the Tower of Babel, where it threatened even God himself. “Go to,” God said, “Let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.” And lo, as a result of quasi-evolutionary divergence, we speak many thousands of mutually unintelligible tongues, the exact number undefined, mostly because dialect grades into language so we can’t decide where one language ends and the next begins. This smearing out is seen both across geographical space (think English worldwide) and through historical time as languages evolve through the centuries (try reading Chaucer). Nevertheless, because language is partly digital, chunked into the discrete semantic units that we call words, it is capable of great fidelity of transmission, especially in written forms. Yet, despite being thus capable, precious little verbal information from our dead ancestors filters down.

But there is another language, also digital, of far greater precision and fidelity of transmission, which does preserve ancestral information, not through a paltry few generations but through hundreds of millions; a parallel language, which is not a human monopoly but is shared by all life: all animals, fungi, plants, bacteria, and archaea; a truly universal language that doesn’t suffer the confusion of dialect drift or trans-generational decay. Nor does it fall victim to the cumulative inflation of my opening fantasy, because it does not grow with each generation. As every schoolchild knows, acquired characteristics are not inherited. The genetic database changes, not cumulatively but by subtraction and addition approximately keeping pace with each other.

More here.

Burn Down the Admissions System

Yascha Mounk in Persuasion:

A few years ago, I listened to Jim Yong Kim, then the President of the World Bank, address the Milken Global Conference, a gathering that is about as plutocratic as it sounds. At the start of his remarks, Kim told the multimillionaires and billionaires who made up the bulk of the audience an anecdote, which he seemed to consider charming, about how he got his job.

A few years ago, I listened to Jim Yong Kim, then the President of the World Bank, address the Milken Global Conference, a gathering that is about as plutocratic as it sounds. At the start of his remarks, Kim told the multimillionaires and billionaires who made up the bulk of the audience an anecdote, which he seemed to consider charming, about how he got his job.

One day, while Kim was still in his previous job as the President of Dartmouth College, his assistant informed him of an unexpected phone call from Tim Geithner, the Secretary of the Treasury. Kim immediately reached for a pen. Naturally, he said, he expected that Geithner would ask for some nephew or family friend of his to get special consideration in the admissions process, and Kim wanted to be ready to jot down the applicant’s name. But to his astonishment, that wasn’t the case: Geithner was actually calling to see whether he might be interested in running the World Bank! (Cue appreciative chuckles from the audience.)

What was remarkable about this anecdote is just how normalized these forms of influence-peddling are in America’s elite.

More here.

The Medley Song

Sunday Poem

Introduction to Poetry

I ask them to take a poem

and hold it up to the light

like a color slide

or press an ear against its hive.

I say drop a mouse into a poem

and watch him probe his way out,

or walk inside the poem’s room

and feel the walls for a light switch.

I want them to waterski

across the surface of a poem

waving at the author’s name on the shore.

But all they want to do

is tie the poem to a chair with rope

and torture a confession out of it.

They begin beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.

by Billy Collins

from The Apple That Astonished Paris

Robert Black (1956 – 2023) Double Bassist

Julian Sands (1958 – 2023) Actor

Bobby Osborne (1931 – 2023) Bluegrass Musician

Saturday, July 1, 2023

Congress Redux?

Aditya Bahl in Sidecar:

Aditya Bahl in Sidecar:

On 7 September last year, the senior Congress leader Rahul Gandhi launched Bharat Jodo Yatra, a protest march to ‘unite India’ against the ‘divisive politics’ of the BJP-led government. Stretching from Kanyakumari, on the southern tip of India, to Jammu and Kashmir in the north, the yatra covered some 3,500 kilometers and twelve states. A number of celebrities made headlines by joining this five-month journey. As did Gandhi’s outfit (a single polo T-shirt throughout the winter), his scraggly beard and his fitness regime (‘fourteen pushups in ten seconds’). The right-wing backlash was predictable: some mocked Gandhi’s Burberry wardrobe, others likened his facial hair to Saddam Hussein’s. Yet, in every state he crossed, the 52-year-old scion of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty saw his approval ratings increase – most of all in Delhi, where they jumped from 32% to 55%. Riding a wave of mass popularity for the first time in his career, Gandhi provided this memorable summation: ‘In the bazaar of hate, I am opening shops of love’. And then, within a few weeks, his star plummeted. On 23 March, a lower Indian court convicted him of making defamatory comments about the surname of the Prime Minister. A day later, he was summarily ejected from parliament.

While Gandhi’s political future is in jeopardy, his nemesis still appears to be untouchable, despite the volatility of his period in office. Over nine years, Narendra Modi has unleashed a devastating series of ‘shock and awe’ operations which have consistently failed to dent his popularity. In November 2016, he withdrew 86% of the circulating currency overnight, costing 10-12 million workers their jobs.

More here.