Category: Recommended Reading

Alan Arkin (1934 – 2023) Actor

Peter Brötzmann (1941 – 2023) Saxophonist

Saturday, July 8, 2023

The Upper West Side Cult That Hid in Plain Sight

Jessica Winter in The New Yorker:

Jessica Winter in The New Yorker:

Cults thrive in isolation, and this poses a challenge for the urban cult leader. Jim Jones, of the Peoples Temple, exerted an unsettling degree of influence on San Francisco politics of the late nineteen-seventies but was eventually forced to flee to his doomed jungle outpost in Guyana. Charles Manson made halting inroads in the late-sixties Los Angeles music scene while his Family hunkered down on the fifty-five-acre Spahn Movie Ranch. Scientology has prominent real-estate holdings in major cities across the world, but its élite management unit, the Sea Org, was originally intended to operate in international waters, in order to evade government and media scrutiny.

At its peak, in the mid- to late seventies, the psychoanalytic association known as the Sullivanian Institute had as many as six hundred patient-members clustered in apartment buildings that the group bought or rented on the cheap on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. They also ran an experimental theatre troupe, called the Fourth Wall, on the Lower East Side. The Sullivanians adhered to the same principles and traditions as many of the ashrams and rural intentional communities of the era: polyamory, communal living, group parenting, socialist politics. But they came to their belief system through the gateway of psychoanalysis, the self-actualization tool of the urbane intellectual. And they enacted their beliefs on a crowded concrete island of nearly a million and a half people, often while holding down high-status jobs as physicians, attorneys, computer programmers, and academics. The institute’s co-founder and reigning tyrant, Saul Newton, who sat atop the organization from the mid-nineteen-fifties until the mid-nineteen-eighties (he died in 1991), may have come closer than any of his far more notorious peers to establishing a truly metropolitan cult—its members visible but its practices obscure.

More here.

Body and Soul

Jack Arden in Sidecar:

Jack Arden in Sidecar:

Last month, in purple passages lauding ‘a master stylist, whose use of punctuation was an art form in itself’, whose literary career was powered by a ‘supercharged prose, all heft and twang’, the usually characterless British broadsheets succumbed to the charms of ‘style’. Journalistic prose gave way to overwriting, as if the subject – the death of Martin Amis – provided a pretext for some formal indulgence, the effusion of pent-up lyricism. If opinions differed as to the quality of his books or the value of his political interventions, all could agree that Amis’s sentences were ‘dazzling’. In these eulogies, style was invariably interpreted as a kind of personal touch, a reflection of the writer’s singular identity: ‘The style was the man’, Sebastian Faulks told The Times. Yet such unanimity created the impression that style was also more than this – something supra-personal, perhaps a class-bound argot, expressed in the shared valediction for Amis’s verbal gifts.

In his obituary for Sidecar, Thomas Meaney added a critical note to the chorus of praise. Amis ‘occasionally succumbed to the literary equivalent of quantitative easing – inflating his sentences with adjectives as if to ward off the collapse of the books that housed them’. The dichotomy, between Amis’s ‘high-flown English’ and its opposite, is a long-standing one. Here the image of inflationary adjectives presumes some ‘real economy’ of plain style, in which parts of speech can find their ‘natural rate’. Judgements about style are often structured around these two dependent poles: at one end, the flowery, the overwritten, the self-reflexive or even autotelic; and at the other, the plain, the clear, the concise and the communicative. Does this distinction, seemingly embedded in our common sense, withstand scrutiny?

More here.

Parallel Systems

Nicholas Jepson in Phenomenal World:

At the start of her three-nation tour of Africa this January, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen spoke to the Associated Press in Senegal, bemoaning the “piling, unsustainable debt” that, she said, “plagued” many African countries. This was a problem, she argued, “related to Chinese investments in Africa.” Two days later Yellen was in Zambia, a country which, having defaulted on its external debt in 2020, was still trying to clinch a final deal with creditors more than two years later. In 2021 the G20 had agreed on the Common Framework, a vague set of guidelines meant to smooth such restructuring talks among low-income debtors and a variety of creditors, each with sometimes contradictory demands. If successful, Yellen stressed, such negotiations would unlock much needed disbursements from a $1.3 billion International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan. The problem, according to Yellen, was that China had become a “barrier to concluding the negotiations.” Back in the US, World Bank President David Malpass told Bloomberg that “China is asking lots of questions in the creditors committees, and that causes delays, that strings out the process.” The following day, the Chinese Embassy in Lusaka released a statement defending China’s role in the Zambian talks, chiding Yellen over US debt ceiling uncertainties and advising that “the biggest contribution that the US can make to the debt issues outside the country is to act on responsible monetary policies, cope with its own debt problem, and stop sabotaging other sovereign countries’ active efforts to solve their debt issues.” In this context, it is hardly surprising that ex-Zambian trade minister Dipak Patel has complained of his country becoming a pawn in a “Common Framework Cold War.”

Global sovereign debt crises are not a new phenomenon. They date as far back as the Panic of 1825, when a wave of defaults by newly independent Latin American states contributed to a financial crisis in London that came close to collapsing the Bank of England.

More here.

Visibility and Erasure: On Louise Nevelson

Jon Raymond and Julia Bryan-Wilson at LitHub:

Jon Raymond: Let’s start simple. How far back does your fascination with Nevelson go? Were there any pivotal moments that led you to write this book? Any signs or portents that guided you?

Jon Raymond: Let’s start simple. How far back does your fascination with Nevelson go? Were there any pivotal moments that led you to write this book? Any signs or portents that guided you?

Julia Bryan-Wilson: I had never written a monographic book before—that is, a close study of a single artist—and I came to her as my subject gradually and hesitantly. I was apprehensive about how I would approach Nevelson’s impressively large and impressively repetitive oeuvre. But I kept returning to her art, especially her wood-based assemblages painted black. Why did this idiom emerge for her in the 1950s and why did she pursue it so insistently until her death?

Within art history, Nevelson’s sculpture is both pervasive and strangely neglected. Though I might have encountered Nevelson pieces in museums as a student, she was not included in the 20th century Western art surveys I took. Nor has there been a robust critical literature dedicated to her as there has been for, as a counter-example, Louise Bourgeois.

more here.

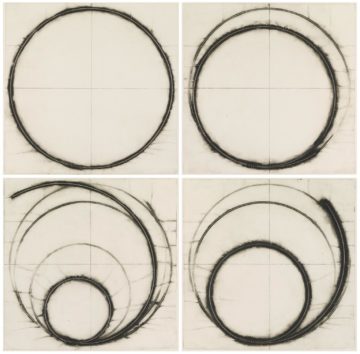

Nevelson in Process, 1977

Sanitizing Heidegger

Richard Wolin at the LARB:

The controversies that have haunted the publication of Heidegger’s work are significant, insofar as they concern not merely occasional and understandable editorial lapses but instead suggest a premeditated policy of substantive editorial cleansing: a strategy whose goal was to systematically and deliberately excise Heidegger’s pro-Nazi sentiments and convictions. As Heidegger scholar Otto Pöggeler observed appositely, “Heidegger is like a fox who sweeps away his traces with his tail.”

The controversies that have haunted the publication of Heidegger’s work are significant, insofar as they concern not merely occasional and understandable editorial lapses but instead suggest a premeditated policy of substantive editorial cleansing: a strategy whose goal was to systematically and deliberately excise Heidegger’s pro-Nazi sentiments and convictions. As Heidegger scholar Otto Pöggeler observed appositely, “Heidegger is like a fox who sweeps away his traces with his tail.”

The problems began with the postwar publication of Heidegger’s lecture courses from the 1930s, as Germany and Europe struggled to climb out from under the ruins of the “German catastrophe.” In Introduction to Metaphysics (1953), Heidegger had falsified his disturbing paean to the “inner truth and greatness of National Socialism,” adding a parenthetical clarification that referenced “the encounter between planetary technology and modern man.” When queried about the authenticity of the passage in question, Heidegger doubled down on his initial duplicity, falsely claiming that the parenthetical remarks had been in the original manuscript but that he had omitted them when the course was first presented in 1935. When, at a later point, scholars sought to establish the veracity of Heidegger’s claim by consulting the original manuscript, they were taken aback to find that the page in question had inexplicably gone missing.

more here.

Why It Took 64 Years to Make a Barbie Movie

Eliana Dockterman in Time:

Barbie is an icon, perhaps the best known toy in the world. As Margot Robbie points out in an interview with me for a TIME cover story, the word “Barbie” has the sort of enviable global recognition only achieved by brands like Coca-Cola. Since her debut in 1959, she has been a staple of the culture, a touchpoint for pop icons like Nicki Minaj, and has become synonymous with a specific shade of pink.

Barbie is an icon, perhaps the best known toy in the world. As Margot Robbie points out in an interview with me for a TIME cover story, the word “Barbie” has the sort of enviable global recognition only achieved by brands like Coca-Cola. Since her debut in 1959, she has been a staple of the culture, a touchpoint for pop icons like Nicki Minaj, and has become synonymous with a specific shade of pink.

And yet it has somehow taken until 2023 for Barbie to make her live-action film debut. On July 21, the doll will finally grace the big screen. While there have been a number of animated Barbie movies and series on Nickelodeon and streaming services, Barbie will be the first live-action movie starring the doll to premiere in theaters. Margot Robbie will play a version of Barbie, but so will Issa Rae, Kate McKinnon, Hari Nef, Alexandra Shipp, and a number of other actors. Ryan Gosling will play just one of many Kens. Every image from the film, beginning with paparazzi shots of Robbie and Gosling rollerskating in spandex, has been dissected online, and Barbiecore has never been hotter.

More here.

Squeak & Gibber: Explanations we use to grapple with our own mortality

John Crowley in Lapham’s Quarterly:

The Hasidim more than other Jewish sects are committed to a life after death—some believe that dead souls can appear to the living. In the oldest Jewish traditions, though, there is little emphasis on a next life; there are almost no revenants or ghosts in the Hebrew Bible, and no afterlife that impresses us as being more than a name for death itself—Sheol is as featureless and blind and inactive as the grave it stands for. The tradition of the soul’s escape from the earth and the body through the spheres derives from Neoplatonic philosophers of late antiquity; I don’t know how it might have become implicated in the funerary rites of the Lubavitcher Hasidim, and no other rabbi I’ve talked to has ever heard of this explanation for the practice, but I was there on that day, giving aid to a soul on its journey. And yet I also know that on the anniversaries of his death, the man I helped to bury is visited by his relations, who place small rocks on his headstone, and pray that he may rest there in peace.

The Hasidim more than other Jewish sects are committed to a life after death—some believe that dead souls can appear to the living. In the oldest Jewish traditions, though, there is little emphasis on a next life; there are almost no revenants or ghosts in the Hebrew Bible, and no afterlife that impresses us as being more than a name for death itself—Sheol is as featureless and blind and inactive as the grave it stands for. The tradition of the soul’s escape from the earth and the body through the spheres derives from Neoplatonic philosophers of late antiquity; I don’t know how it might have become implicated in the funerary rites of the Lubavitcher Hasidim, and no other rabbi I’ve talked to has ever heard of this explanation for the practice, but I was there on that day, giving aid to a soul on its journey. And yet I also know that on the anniversaries of his death, the man I helped to bury is visited by his relations, who place small rocks on his headstone, and pray that he may rest there in peace.

I sometimes think that humanity’s greatest feats of rationality lie not in the useful discriminations and distinctions made by physics or philosophy within the continuum of life and time but rather in the inventions and explanations we have devised to grapple with the unresolvable ambiguities of our mortality.

More here.

Friday, July 7, 2023

The Case For Effective Altruism

Matt Lutz in Persuasion:

In Peter Singer’s paper, “Famine, Affluence, and Morality,” Singer defends two core moral propositions. The first is that “suffering and death from lack of food, shelter, and medical care is bad.” That should be uncontroversial. Singer doesn’t even argue for it, simply saying that if you disagree with that claim, you’re not his target audience. The second proposition is that “if it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it.”

In Peter Singer’s paper, “Famine, Affluence, and Morality,” Singer defends two core moral propositions. The first is that “suffering and death from lack of food, shelter, and medical care is bad.” That should be uncontroversial. Singer doesn’t even argue for it, simply saying that if you disagree with that claim, you’re not his target audience. The second proposition is that “if it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it.”

Singer illustrates this second proposition with the following thought experiment: suppose you are walking near a shallow pond and see a young child drowning. Unless someone jumps in to rescue the child, he will die. If you jump in, you can easily save him. However, you’re wearing very nice, expensive clothes, and those clothes will be ruined if you jump in. If you save the drowning child, you will prevent something bad from happening, and you will have to sacrifice to do it. But the thing that you will sacrifice, your nice clothes, is not of comparable moral importance to the life of a child. So you ought, morally, to save the child. If you don’t, you’re doing something profoundly morally wrong.

More here. And the case against EA, also in Persuasion, is here.

India’s approach to global warming cannot mirror the West

Usha Alexander in Shunya’s Notes:

Given India’s long coastline and its total reliance on predictable patterns of rainfall and steady rates of snow-replenished, glacial meltwater to feed its people, the mounting threats of climate change are real and urgent. It behoves us, as a nation, to take aggressive action to mitigate these threats by reducing our use of coal, oil and gas, by preserving and expanding mature forests. But, given that we demand more electricity and gasoline to power our increasingly urban, consumerist lives while pursuing a model of development based on pulling more people into energy-intensive lifestyles, the central government has declared its intention to more than double energy generation capacity by 2030, mostly by rapidly expanding low-carbon energy sources. As a low-emissions, renewable resource, the Polavaram dam might be regarded as an example of “green” energy, never mind its immense ecological and human costs.

Given India’s long coastline and its total reliance on predictable patterns of rainfall and steady rates of snow-replenished, glacial meltwater to feed its people, the mounting threats of climate change are real and urgent. It behoves us, as a nation, to take aggressive action to mitigate these threats by reducing our use of coal, oil and gas, by preserving and expanding mature forests. But, given that we demand more electricity and gasoline to power our increasingly urban, consumerist lives while pursuing a model of development based on pulling more people into energy-intensive lifestyles, the central government has declared its intention to more than double energy generation capacity by 2030, mostly by rapidly expanding low-carbon energy sources. As a low-emissions, renewable resource, the Polavaram dam might be regarded as an example of “green” energy, never mind its immense ecological and human costs.

But, to get a real handle on our predicament, we cannot ignore these costs. We must reckon with the underlying reality that our mounting harms to natural systems have thrust us into a condition of ecological overshoot. This means we are depleting essential resources—perhaps most alarmingly, healthy soils—by annihilating living systems, extracting resources and producing pollution at a rate faster than planetary systems can replenish themselves, faster than natural geochemical cycles can restabilise themselves or the beleaguered biosphere can regain its integrity.

More here.

The Long Reach of China’s Demographic Destiny

Yi Fuxian in Project Syndicate:

When Western leaders welcomed China into the World Trade Organization in 2001, most assumed that they were creating the conditions for eventual democratization. A growing Chinese middle class, they assumed, would demand greater accountability from the government, ultimately creating so much pressure that the autocrats would step aside and allow for a democratic transition. This political fantasy underpinned the Sino-American relationship for decades.

When Western leaders welcomed China into the World Trade Organization in 2001, most assumed that they were creating the conditions for eventual democratization. A growing Chinese middle class, they assumed, would demand greater accountability from the government, ultimately creating so much pressure that the autocrats would step aside and allow for a democratic transition. This political fantasy underpinned the Sino-American relationship for decades.

But it wasn’t to be. The Communist Party of China (CPC) has been regressing on all fronts, reasserting more top-down control over the economy and tightening censorship and other forms of social and political control. It has been led down this path by the legacy of the one-child policy, which fundamentally reshaped the country’s demographics and economy.

More here.

Orson Welles on Houdini in Russia, and on Cold Reading

What an Owl Knows

Simon Worrall at The Guardian:

The book is not just about owls, though, but about the people who study them. There are many scientists and conservationists, who have, like Ackerman, fallen under the spell of these endearing creatures. People like José Luis Peña, a neuroscientist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in New York, who has discovered that a barn owl’s sound localisation system relies on sophisticated mathematical computations to pinpoint its prey. Or zoomusicologist Magnus Robb, who studies hoots.

The book is not just about owls, though, but about the people who study them. There are many scientists and conservationists, who have, like Ackerman, fallen under the spell of these endearing creatures. People like José Luis Peña, a neuroscientist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in New York, who has discovered that a barn owl’s sound localisation system relies on sophisticated mathematical computations to pinpoint its prey. Or zoomusicologist Magnus Robb, who studies hoots.

“If anyone knows anything about anything,” Winnie-the-Pooh famously remarked, “it’s Owl who knows something about something.” And it turns out, owls know a lot. Equipped with super-sensitive hearing, great grey owls in the far north are capable of detecting and catching voles deep beneath the snow by sound alone. Scientists have even discovered that owls process sound in the visual centre of their brains, so they may actually get a “picture” of the environment they are hearing.

more here.

Effing Philosophy

Jennifer Szalai at the NY Times:

When setting out to write “A Terribly Serious Adventure: Philosophy and War at Oxford, 1900-1960,” Nikhil Krishnan certainly had his work cut out for him. How to generate excitement for a “much-maligned” philosophical tradition that hinges on finicky distinctions in language? Whose main figures were mostly well-to-do white men, routinely caricatured — and not always unfairly — for being suspicious of foreign ideas and imperiously, insufferably smug?

When setting out to write “A Terribly Serious Adventure: Philosophy and War at Oxford, 1900-1960,” Nikhil Krishnan certainly had his work cut out for him. How to generate excitement for a “much-maligned” philosophical tradition that hinges on finicky distinctions in language? Whose main figures were mostly well-to-do white men, routinely caricatured — and not always unfairly — for being suspicious of foreign ideas and imperiously, insufferably smug?

Krishnan, a philosopher at Cambridge, confesses up front that he, too, felt frustrated and resentful when he first encountered “linguistic” or “analytic” philosophy as a student at Oxford. He had wanted to study philosophy because he associated it with mysterious qualities like “depth” and “vision.” He consequently assumed that philosophical writing had to be densely “allusive”; after all, it was getting at something “ineffable.” But his undergraduate tutor, responding to Krishnan’s muddled excuse for some muddled writing, would have none of it. “On the contrary, these sorts of things are entirely and eminently effable,” the tutor said. “And I should be very grateful if you’d try to eff a few of them for your essay next week.”

more here.

Nikhil Krishnan on the History and Future of Analytic Philosophy

Shadows at Noon: The South Asian Twentieth Century – charming, genre-defying study

William Dalrymple in The Guardian:

The sudden rise of India over the past few years has taken many western observers by surprise. The Indian economy has quadrupled in size in a generation. Its ancient reputation as a centre for mathematics and scientific skills remains intact, and Indian software engineers increasingly dominate Silicon Valley. India now has the largest population in the world and is clearly on its way to becoming the third economic superpower. Its economy overtook the UK last autumn and will overtake Germany and Japan within the next decade. The only questions are whether it is the US, China or India that will dominate the world by the end of this century, and what sort of India that will be.

The sudden rise of India over the past few years has taken many western observers by surprise. The Indian economy has quadrupled in size in a generation. Its ancient reputation as a centre for mathematics and scientific skills remains intact, and Indian software engineers increasingly dominate Silicon Valley. India now has the largest population in the world and is clearly on its way to becoming the third economic superpower. Its economy overtook the UK last autumn and will overtake Germany and Japan within the next decade. The only questions are whether it is the US, China or India that will dominate the world by the end of this century, and what sort of India that will be.

Little of this would have surprised our ancestors who first sailed to India with the East India Company at the time of Shakespeare. India then had a population of around 150 million – about a fifth of the world’s total – and was producing about a quarter of global manufacturing; indeed, in many ways it was the world’s industrial powerhouse and the leader in manufactured textiles. The idea that India was ever a poor, famine-struck country is a relatively recent one, dating only from the period of British rule: historically, South Asia was always famous as the richest region of the globe, whose fertile soils gave two harvests a year and whose mines groaned with mineral riches.

More here.

Seven Amazing Accomplishments the James Webb Telescope Achieved in Its First Year

Dan Falk in Smithsonian:

The James Webb Space Telescope, the largest and most sophisticated space observatory ever built, has been sending back images and data for almost a full year now—and in that time it has delivered a treasure trove of information about everything from stars and planetary systems in our own galactic neighborhood to distant galaxies that formed when the universe was a tiny fraction of its current age. Webb has also sent back stunning images that surpass those garnered by its famous predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope.

The James Webb Space Telescope, the largest and most sophisticated space observatory ever built, has been sending back images and data for almost a full year now—and in that time it has delivered a treasure trove of information about everything from stars and planetary systems in our own galactic neighborhood to distant galaxies that formed when the universe was a tiny fraction of its current age. Webb has also sent back stunning images that surpass those garnered by its famous predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope.

Webb and Hubble are quite different instruments. For starters, while Hubble is primarily sensitive to visible light, Webb records infrared light that’s invisible to the unaided eye. These longer wavelengths of light pass through clouds of gas and dust that block visible light, letting the telescope peer past such obstacles. It also has a size advantage: While Hubble’s main mirror is 8 feet across, Webb employs an array of 18 small hexagonal mirrors that function like a single mirror 21 feet across.

More here.