Kelsey Piper in Asterisk:

It’d be a mistake to characterize the risk of human extinction from artificial intelligence as a “fringe” concern now hitting the mainstream, or a decoy to distract from current harms caused by AI systems. Alan Turing, one of the fathers of modern computing, famously wrote in 1951 that “once the machine thinking method had started, it would not take long to outstrip our feeble powers. … At some stage therefore we should have to expect the machines to take control.” His colleague I. J. Good agreed; more recently, so did Stephen Hawking. When today’s luminaries warn of “extinction risk” from artificial intelligence, they are in good company, restating a worry that has been around as long as computers. These concerns predate the founding of any of the current labs building frontier AI, and the historical trajectory of these concerns is important to making sense of our present-day situation. To the extent that frontier labs do focus on safety, it is in large part due to advocacy by researchers who do not hold any financial stake in AI. Indeed, some of them would prefer AI didn’t exist at all.

It’d be a mistake to characterize the risk of human extinction from artificial intelligence as a “fringe” concern now hitting the mainstream, or a decoy to distract from current harms caused by AI systems. Alan Turing, one of the fathers of modern computing, famously wrote in 1951 that “once the machine thinking method had started, it would not take long to outstrip our feeble powers. … At some stage therefore we should have to expect the machines to take control.” His colleague I. J. Good agreed; more recently, so did Stephen Hawking. When today’s luminaries warn of “extinction risk” from artificial intelligence, they are in good company, restating a worry that has been around as long as computers. These concerns predate the founding of any of the current labs building frontier AI, and the historical trajectory of these concerns is important to making sense of our present-day situation. To the extent that frontier labs do focus on safety, it is in large part due to advocacy by researchers who do not hold any financial stake in AI. Indeed, some of them would prefer AI didn’t exist at all.

But while the risk of human extinction from powerful AI systems is a long-standing concern and not a fringe one, the field of trying to figure out how to solve that problem was until very recently a fringe field, and that fact is profoundly important to understanding the landscape of AI safety work today.

More here.

Gravitational waves are back, and they’re bigger than ever.

Gravitational waves are back, and they’re bigger than ever. The internet was created by the U.S. military as a way to preserve communications to missile silos in the event of a Soviet nuclear attack:

The internet was created by the U.S. military as a way to preserve communications to missile silos in the event of a Soviet nuclear attack: 350 pages into Vikram Chandra’s epic novel Red Earth and Pouring Rain, a particular story within a story within a story caught my attention the first time I read it in the mid-aughts. Perhaps one day I’ll pen a lecture on the image of printers within contemporary literature. This one involves the wily Calcutta printer Sorkar, working on commission to an aloof Englishman named Markline. Sorkar wanders his shopfloor, occasionally handing out special letters to his Bengali typesetters to substitute for their fonts. What do these letters spell? It turns out that they are a cipher, a means of encoding secret linguistic jabs against the printer’s British master. They range from political statements such as “The Company makes widows and famines, and calls it peace” to the simple and effective, “Fuck you.”

350 pages into Vikram Chandra’s epic novel Red Earth and Pouring Rain, a particular story within a story within a story caught my attention the first time I read it in the mid-aughts. Perhaps one day I’ll pen a lecture on the image of printers within contemporary literature. This one involves the wily Calcutta printer Sorkar, working on commission to an aloof Englishman named Markline. Sorkar wanders his shopfloor, occasionally handing out special letters to his Bengali typesetters to substitute for their fonts. What do these letters spell? It turns out that they are a cipher, a means of encoding secret linguistic jabs against the printer’s British master. They range from political statements such as “The Company makes widows and famines, and calls it peace” to the simple and effective, “Fuck you.” “We got down from the car and went inside.”

“We got down from the car and went inside.” During the summer months in the Oxfordshire town where I live, I go swimming in the nearby 50-metre lido. With my inelegantly slow breaststroke, from time to time I accidentally gulp some of the pool’s opulent, chlorine-clean 5.9m litres of water. Sometimes, I swim while it’s raining, when fewer people brave it, alone in my lane with the strangely comforting feeling of having water above and below me. I stand a bottle of water at the end of the lane, to drink from halfway through my swim. I normally have a shower afterwards, even if I’ve showered that morning. I live a wet, drenched, quenched existence. But, as I discovered, this won’t last. I am living on borrowed time and borrowed water.

During the summer months in the Oxfordshire town where I live, I go swimming in the nearby 50-metre lido. With my inelegantly slow breaststroke, from time to time I accidentally gulp some of the pool’s opulent, chlorine-clean 5.9m litres of water. Sometimes, I swim while it’s raining, when fewer people brave it, alone in my lane with the strangely comforting feeling of having water above and below me. I stand a bottle of water at the end of the lane, to drink from halfway through my swim. I normally have a shower afterwards, even if I’ve showered that morning. I live a wet, drenched, quenched existence. But, as I discovered, this won’t last. I am living on borrowed time and borrowed water. As part of our event series with The Philosopher, Amna Akbar sat down with Bernard Harcourt, legal scholar and professor of political science at Columbia University, to discuss his new book, Cooperation: A Political, Economic, and Social Theory. In the course of their conversation, moderated by Philosopher editor Anthony Morgan, they discuss the failure of traditional electoral politics and mass mobilization, existing cooperative efforts, our punitive society, and how we might build democratic self-governance. Below is a transcript of their conversation, which has been edited for clarity and concision.

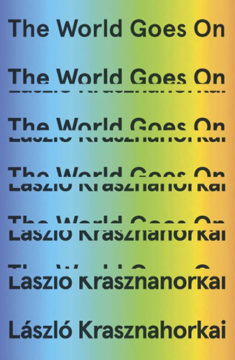

As part of our event series with The Philosopher, Amna Akbar sat down with Bernard Harcourt, legal scholar and professor of political science at Columbia University, to discuss his new book, Cooperation: A Political, Economic, and Social Theory. In the course of their conversation, moderated by Philosopher editor Anthony Morgan, they discuss the failure of traditional electoral politics and mass mobilization, existing cooperative efforts, our punitive society, and how we might build democratic self-governance. Below is a transcript of their conversation, which has been edited for clarity and concision. Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai has become a more familiar name to English speaking readers over the last few years thanks to his receipt of the Man Booker International Prize in 2015. Nevertheless, his is a name that remains shrouded in a certain mystique, due in part to his gnomic responses in interviews, and to the notorious difficulty of his work, with its breathtakingly long sentences and apocalyptic, melancholic themes. The World Goes On, which has been shortlisted for 2018 Man Booker International Prize, continues to explore these themes, albeit in a less menacing or apocalyptic tone than some of his earlier works.

Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai has become a more familiar name to English speaking readers over the last few years thanks to his receipt of the Man Booker International Prize in 2015. Nevertheless, his is a name that remains shrouded in a certain mystique, due in part to his gnomic responses in interviews, and to the notorious difficulty of his work, with its breathtakingly long sentences and apocalyptic, melancholic themes. The World Goes On, which has been shortlisted for 2018 Man Booker International Prize, continues to explore these themes, albeit in a less menacing or apocalyptic tone than some of his earlier works. One March day in 1742, a very unusual man set up a table on a busy Philadelphia street. Benjamin Lay was sixty-one years old, wore humble homespun clothes, and sported a long beard. His head was large and his eyes luminous, but his posture and height immediately set him apart: he had a stooped back and stood a little over four feet tall. He carefully laid out a few teacups and saucers, delicate objects that had been treasured by his wife before she passed away, and then proceeded to smash them with a hammer, crushing the dishes with dramatic flair. With each loud blow, bits of ceramic flying, he denounced the “tyrants” in India and the Caribbean who mistreated the workers who harvested the tea and enslaved the people who produced the sugar that his Pennsylvania neighbors consumed.

One March day in 1742, a very unusual man set up a table on a busy Philadelphia street. Benjamin Lay was sixty-one years old, wore humble homespun clothes, and sported a long beard. His head was large and his eyes luminous, but his posture and height immediately set him apart: he had a stooped back and stood a little over four feet tall. He carefully laid out a few teacups and saucers, delicate objects that had been treasured by his wife before she passed away, and then proceeded to smash them with a hammer, crushing the dishes with dramatic flair. With each loud blow, bits of ceramic flying, he denounced the “tyrants” in India and the Caribbean who mistreated the workers who harvested the tea and enslaved the people who produced the sugar that his Pennsylvania neighbors consumed. Temnothorax nylanderi

Temnothorax nylanderi Over the last decade, dozens of companies and nearly all large countries have vowed to stop demolishing forests, a practice that destroys entire communities of wildlife and pollutes the air with enormous amounts of carbon dioxide. A big climate conference in Glasgow, in the fall of 2021, produced the most significant pledge to date:

Over the last decade, dozens of companies and nearly all large countries have vowed to stop demolishing forests, a practice that destroys entire communities of wildlife and pollutes the air with enormous amounts of carbon dioxide. A big climate conference in Glasgow, in the fall of 2021, produced the most significant pledge to date:  T

T