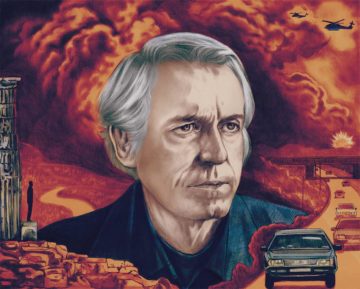

Siddhartha Deb in The Nation:

An assassin works from a partial understanding of the world. If not literally a hashishi, as suggested by the word’s etymology, an assassin must nevertheless see the world in tunnel vision, his victim viewed through the lens of a scope. The vast, complex network of humanity to which he and his victim belong, with contending narratives and blurred individual motives, cannot be allowed to exist. To do so would be to fail as an assassin.

An assassin works from a partial understanding of the world. If not literally a hashishi, as suggested by the word’s etymology, an assassin must nevertheless see the world in tunnel vision, his victim viewed through the lens of a scope. The vast, complex network of humanity to which he and his victim belong, with contending narratives and blurred individual motives, cannot be allowed to exist. To do so would be to fail as an assassin.

A Don DeLillo novel grasps both the assassin’s monomania and the contradictory, counterintuitive world of which it is a part. It is capable of displaying fidelity to both perspectives, brushing one against the other to edge its way toward a fictional truth that neither can uncover on its own. Six novels published in the 1970s established this principle, but the approach truly came into its own only with Libra (1988), DeLillo’s ninth novel. “Hashish. Interesting, interesting word,” a character says to Lee Harvey Oswald as the novel uncoils toward its climactic moment in Dallas with the Kennedy assassination. “Arabic. It’s the source of the word assassin.”

More here.

We cannot be sure what animals are, because we cannot be sure what we are. We are beasts among beasts, and something qualitatively different. The boundary between these two kinds of being is always ready to dissolve by moonlight.

We cannot be sure what animals are, because we cannot be sure what we are. We are beasts among beasts, and something qualitatively different. The boundary between these two kinds of being is always ready to dissolve by moonlight. The Supreme Court last week outlawed the use of race-based affirmative action in college admissions. That practice was understandable and even necessary 60 years ago. The question I have asked for some time was precisely how long it would be required to continue. I’d personally come to believe that preferences focused on socioeconomic factors — wealth, income, even neighborhood — would accomplish more good while requiring less straightforward unfairness.

The Supreme Court last week outlawed the use of race-based affirmative action in college admissions. That practice was understandable and even necessary 60 years ago. The question I have asked for some time was precisely how long it would be required to continue. I’d personally come to believe that preferences focused on socioeconomic factors — wealth, income, even neighborhood — would accomplish more good while requiring less straightforward unfairness. Every life contains pain. Even the perfect life, the life where you have everything you want, hides its own unique struggles. Writing in The Genealogy of Morals (1887),

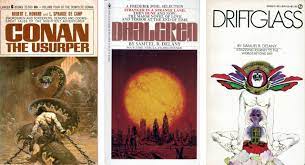

Every life contains pain. Even the perfect life, the life where you have everything you want, hides its own unique struggles. Writing in The Genealogy of Morals (1887),  In the stellar neighborhood of American letters, there have been few minds as generous, transgressive, and polymathically brilliant as Samuel Delany’s. Many know him as the country’s first prominent Black author of science fiction, who transformed the field with richly textured, cerebral novels like “Babel-17” (1966) and “Dhalgren” (1975). Others know the revolutionary chronicler of gay life, whose autobiography, “The Motion of Light in Water” (1988), stands as an essential document of pre-Stonewall New York. Still others know the professor, the pornographer, or the prolific essayist whose purview extends from cyborg feminism to Biblical philology.

In the stellar neighborhood of American letters, there have been few minds as generous, transgressive, and polymathically brilliant as Samuel Delany’s. Many know him as the country’s first prominent Black author of science fiction, who transformed the field with richly textured, cerebral novels like “Babel-17” (1966) and “Dhalgren” (1975). Others know the revolutionary chronicler of gay life, whose autobiography, “The Motion of Light in Water” (1988), stands as an essential document of pre-Stonewall New York. Still others know the professor, the pornographer, or the prolific essayist whose purview extends from cyborg feminism to Biblical philology. Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, has a knack for taking an unassuming organism and showing it’s capable of the darnedest things. He and his team once extracted skin cells from a frog embryo and cultivated them on their own. With no other cell types around, they were not “bullied,” as he put it, into forming skin tissue. Instead, they reassembled into a new organism of sorts, a “

Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, has a knack for taking an unassuming organism and showing it’s capable of the darnedest things. He and his team once extracted skin cells from a frog embryo and cultivated them on their own. With no other cell types around, they were not “bullied,” as he put it, into forming skin tissue. Instead, they reassembled into a new organism of sorts, a “

When the notable figures of our day pass away, they wind up on our screens, short clips documenting their achievements, talking heads discussing their influence. The quiet lives, though, pass on soundlessly in the background. And yet those are the lives in our skin, guiding us from breakfast to bed. They’re the lives that have made us, that keep the world turning.

When the notable figures of our day pass away, they wind up on our screens, short clips documenting their achievements, talking heads discussing their influence. The quiet lives, though, pass on soundlessly in the background. And yet those are the lives in our skin, guiding us from breakfast to bed. They’re the lives that have made us, that keep the world turning. We have just experienced the hottest day ever recorded on Earth – for the second day in a row. The average global air temperature recorded 2 metres above Earth’s surface hit 17.18°C (62.92°F) on 4 July,

We have just experienced the hottest day ever recorded on Earth – for the second day in a row. The average global air temperature recorded 2 metres above Earth’s surface hit 17.18°C (62.92°F) on 4 July,  In the mid-1920s, the mood in the United States was buoyant. After years of surging economic growth, fuelled by expansion in the automobile industry and speculation in financial markets, the United States had the lowest debt of any large industrial nation. The future looked just as rosy. A 1926 article in The Wall Street Journal noted how “American wealth has doubled in the past dozen years”, delivering “a rate of progress that has never been known in Europe”.

In the mid-1920s, the mood in the United States was buoyant. After years of surging economic growth, fuelled by expansion in the automobile industry and speculation in financial markets, the United States had the lowest debt of any large industrial nation. The future looked just as rosy. A 1926 article in The Wall Street Journal noted how “American wealth has doubled in the past dozen years”, delivering “a rate of progress that has never been known in Europe”. Among the literary genres, biography appears to be thriving. Perhaps it satisfies some element of life writing we also get from fiction, adding a dose of gossip and the illusion that we can actually know the truth of other people’s lives. There is always more than one way to tell a story. Some good recent biographies have been thematic or experimental: Katherine Rundell on John Donne, Frances Wilson on D. H. Lawrence, Andrew S. Curran on Diderot, Clare Carlisle on Kierkegaard. We have authoritative doorstoppers from Langdon Hammer on James Merrill to Heather Clark’s numbingly detailed book on Sylvia Plath. And we find a happy medium-sized biography in Mark Eisner’s on Neruda or Ann-Marie Priest’s on the great Australian poet Gwen Harwood. Among the best of these, Brigitta Olubas’ Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life is not overstuffed or particularly arcane in structure, not weighted down with newly discovered scandal, but lucidly and even gracefully organized, guided by a compelling thesis.

Among the literary genres, biography appears to be thriving. Perhaps it satisfies some element of life writing we also get from fiction, adding a dose of gossip and the illusion that we can actually know the truth of other people’s lives. There is always more than one way to tell a story. Some good recent biographies have been thematic or experimental: Katherine Rundell on John Donne, Frances Wilson on D. H. Lawrence, Andrew S. Curran on Diderot, Clare Carlisle on Kierkegaard. We have authoritative doorstoppers from Langdon Hammer on James Merrill to Heather Clark’s numbingly detailed book on Sylvia Plath. And we find a happy medium-sized biography in Mark Eisner’s on Neruda or Ann-Marie Priest’s on the great Australian poet Gwen Harwood. Among the best of these, Brigitta Olubas’ Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life is not overstuffed or particularly arcane in structure, not weighted down with newly discovered scandal, but lucidly and even gracefully organized, guided by a compelling thesis. IN A 2013 AFTERWORD

IN A 2013 AFTERWORD For the first thirty years of my life, I lived within a one-mile radius of Willesden Green Tube Station. It’s true I went to college—I even moved to East London for a bit—but such interludes were brief. I soon returned to my little corner of North West London. Then suddenly, quite abruptly, I left not just the city but England itself. First for Rome, then Boston, and then my beloved New York, where I stayed ten years. When friends asked why I’d left the country, I’d sometimes answer with a joke: Because I don’t want to write a historical novel. Perhaps it was an in-joke: only other English novelists really understood what I meant by it. And there were other, more obvious reasons. My English father had died. My Jamaican mother was pursuing a romance in Ghana. I myself had married an Irish poet who liked travel and adventure and had left the island of his birth at the age of eighteen. My ties to England seemed to be evaporating. I would not say I was entirely tired of London. No, I was not yet—in

For the first thirty years of my life, I lived within a one-mile radius of Willesden Green Tube Station. It’s true I went to college—I even moved to East London for a bit—but such interludes were brief. I soon returned to my little corner of North West London. Then suddenly, quite abruptly, I left not just the city but England itself. First for Rome, then Boston, and then my beloved New York, where I stayed ten years. When friends asked why I’d left the country, I’d sometimes answer with a joke: Because I don’t want to write a historical novel. Perhaps it was an in-joke: only other English novelists really understood what I meant by it. And there were other, more obvious reasons. My English father had died. My Jamaican mother was pursuing a romance in Ghana. I myself had married an Irish poet who liked travel and adventure and had left the island of his birth at the age of eighteen. My ties to England seemed to be evaporating. I would not say I was entirely tired of London. No, I was not yet—in  Injecting ageing monkeys with a ‘longevity factor’ protein can improve their cognitive function, a study reveals. The findings, published on 3 July in Nature Aging

Injecting ageing monkeys with a ‘longevity factor’ protein can improve their cognitive function, a study reveals. The findings, published on 3 July in Nature Aging