Dan Fox and Richard Hodson in Nature:

Artificial intelligence is booming. Technology companies are pouring trillions of dollars into research and infrastructure, and millions of people now interact with AI in one form or another. But what is it all for?

Artificial intelligence is booming. Technology companies are pouring trillions of dollars into research and infrastructure, and millions of people now interact with AI in one form or another. But what is it all for?

To find out, Nature spoke to six people at the forefront of AI development — people who are driving the technology’s development and adoption, and those who are preparing society to adapt to its rapid rise.

In this video series, they describe their greatest ambitions for the technology, their expectations of where and how it will be adopted in the coming years, and their concerns for the future.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

We are at that strange stage in the adoption curve of a revolutionary technology at which two seemingly contradictory things are true at the same time: It has become clear that artificial intelligence will transform the world. And the technology’s immediate impact is still sufficiently small that it just about remains possible to pretend that this won’t be the case.

We are at that strange stage in the adoption curve of a revolutionary technology at which two seemingly contradictory things are true at the same time: It has become clear that artificial intelligence will transform the world. And the technology’s immediate impact is still sufficiently small that it just about remains possible to pretend that this won’t be the case. Last season on Broadway, one of the most buzzworthy shows was Kip Williams’s adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s novel “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” Originally presented by the Sydney Theater Company, the production featured 26 characters, all played by “Succession” actress Sarah Snook. When the show moved to London’s West End, Snook won an Olivier Award; when it came to Broadway, she won a Tony. Though the show was thoroughly modern, with plenty of technological wizardry, the story was not. Wilde’s novel was published in 1891. And that prompts the question: How is it that “Dorian Gray” continues to be relevant to modern audiences?

Last season on Broadway, one of the most buzzworthy shows was Kip Williams’s adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s novel “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” Originally presented by the Sydney Theater Company, the production featured 26 characters, all played by “Succession” actress Sarah Snook. When the show moved to London’s West End, Snook won an Olivier Award; when it came to Broadway, she won a Tony. Though the show was thoroughly modern, with plenty of technological wizardry, the story was not. Wilde’s novel was published in 1891. And that prompts the question: How is it that “Dorian Gray” continues to be relevant to modern audiences? Before a car crash in 2008 left her paralysed from the neck down, Nancy Smith enjoyed playing the piano. Years later, Smith started making music again, thanks to an implant that recorded and analysed her brain activity. When she imagined playing an on-screen keyboard, her

Before a car crash in 2008 left her paralysed from the neck down, Nancy Smith enjoyed playing the piano. Years later, Smith started making music again, thanks to an implant that recorded and analysed her brain activity. When she imagined playing an on-screen keyboard, her  During the last quarter century, there has been an explosion of scholarship by philosophers of physics and, especially, historians of philosophy on Isaac Newton and his reception in philosophy. This growing interest is prima facie puzzling because Newton did not write a major philosophical work. And while he clearly elicited important philosophical responses (e.g., by Du Châtelet, Kant, Hume, etc.) and engendered important philosophical debates (e.g., Leibniz-Clarke), this does not justify or explain the growing attention. After all, not every person who was a significant interlocutor to philosophers in his own day should be subject of study by a community of historians of philosophy today. (We largely don’t do this for Digby, Mersenne, Riccioli, William Harvey, Kepler, Hooke, Halley, or De Volder, etc.) That Newton was seminal to the history of science and mathematics is insufficiently explanatory (because there is relatively little philosophical scholarship on Euler, the Bernoullis, etc.).

During the last quarter century, there has been an explosion of scholarship by philosophers of physics and, especially, historians of philosophy on Isaac Newton and his reception in philosophy. This growing interest is prima facie puzzling because Newton did not write a major philosophical work. And while he clearly elicited important philosophical responses (e.g., by Du Châtelet, Kant, Hume, etc.) and engendered important philosophical debates (e.g., Leibniz-Clarke), this does not justify or explain the growing attention. After all, not every person who was a significant interlocutor to philosophers in his own day should be subject of study by a community of historians of philosophy today. (We largely don’t do this for Digby, Mersenne, Riccioli, William Harvey, Kepler, Hooke, Halley, or De Volder, etc.) That Newton was seminal to the history of science and mathematics is insufficiently explanatory (because there is relatively little philosophical scholarship on Euler, the Bernoullis, etc.). The Lord, Soraya Antonius’s vivid chronicle of Palestinian life before the Nakba of 1948, is a novel that moves fast, driven by fury and passion. Tales are told within tales; there are jump cuts and flashbacks. Antonius’s eye is as keen as her wit. The narrator of the book, which was first published in 1986, is an unnamed woman journalist in the Lebanon of the early eighties. She is covering current events—the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacres are obliquely referred to at one point—but she also takes an interest in the region’s past, and is particularly curious to find out about a young man named Tareq, who grew up under the British Mandate and played a significant role in the 1936–1939 Palestinian uprising against colonial rule. Her curiosity leads her to the elderly Miss Alice, an Englishwoman who was Tareq’s teacher in a mission school founded by her father at the start of the twentieth century. Tareq, Miss Alice tells the narrator, was a boy of humble background and an undistinguished student, who, however, possessed uncanny powers that Miss Alice can’t really account for. How he put those powers to use will be the novel’s story.

The Lord, Soraya Antonius’s vivid chronicle of Palestinian life before the Nakba of 1948, is a novel that moves fast, driven by fury and passion. Tales are told within tales; there are jump cuts and flashbacks. Antonius’s eye is as keen as her wit. The narrator of the book, which was first published in 1986, is an unnamed woman journalist in the Lebanon of the early eighties. She is covering current events—the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacres are obliquely referred to at one point—but she also takes an interest in the region’s past, and is particularly curious to find out about a young man named Tareq, who grew up under the British Mandate and played a significant role in the 1936–1939 Palestinian uprising against colonial rule. Her curiosity leads her to the elderly Miss Alice, an Englishwoman who was Tareq’s teacher in a mission school founded by her father at the start of the twentieth century. Tareq, Miss Alice tells the narrator, was a boy of humble background and an undistinguished student, who, however, possessed uncanny powers that Miss Alice can’t really account for. How he put those powers to use will be the novel’s story. My hunch is that the contemporary artworks likeliest to one day appear prescient, albeit not always in reassuring ways, will come from para-artistic digital practices, whether artistic experiments with AI; so-called Red Chip art (which Annie Armstrong of Artnet News defines as works with flashy aesthetics that abjure art history); or folk forms such as NFTs, memes, or TikTok lore videos. What these practices have in common is not just that they’re relatively new, with strong ties to digital culture, but also that they’re only somewhat recognizable as great art, or even art at all, under our inherited value systems. Traditionalists gasp, often justifiably, at the ethical and aesthetic challenges AI art poses, or at Red Chip art’s tawdriness, or at digital folk art’s simplicity. But such practices are telling the old culture what’s happening to it, even if the message isn’t what most fine arts audiences want to hear.

My hunch is that the contemporary artworks likeliest to one day appear prescient, albeit not always in reassuring ways, will come from para-artistic digital practices, whether artistic experiments with AI; so-called Red Chip art (which Annie Armstrong of Artnet News defines as works with flashy aesthetics that abjure art history); or folk forms such as NFTs, memes, or TikTok lore videos. What these practices have in common is not just that they’re relatively new, with strong ties to digital culture, but also that they’re only somewhat recognizable as great art, or even art at all, under our inherited value systems. Traditionalists gasp, often justifiably, at the ethical and aesthetic challenges AI art poses, or at Red Chip art’s tawdriness, or at digital folk art’s simplicity. But such practices are telling the old culture what’s happening to it, even if the message isn’t what most fine arts audiences want to hear. If Altman likes you, he will recommend that you read The Beginning of Infinity, by a British physicist who believes all evils and failures are due to insufficient knowledge. “Everything that is not forbidden by laws of nature is achievable, given the right knowledge.” We have entered “the beginning of infinity,” a period of unbounded progress.

If Altman likes you, he will recommend that you read The Beginning of Infinity, by a British physicist who believes all evils and failures are due to insufficient knowledge. “Everything that is not forbidden by laws of nature is achievable, given the right knowledge.” We have entered “the beginning of infinity,” a period of unbounded progress. A

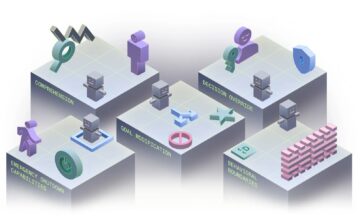

A This paper argues that humanity is on track to develop superintelligent AI systems that would be fundamentally uncontrollable by humans. We define “meaningful human control” as requiring five properties: comprehensibility, goal modification, behavioral boundaries, decision override, and emergency shutdown capabilities. We then demonstrate through three complementary arguments why this level of control over superintelligence is essentially unattainable.

This paper argues that humanity is on track to develop superintelligent AI systems that would be fundamentally uncontrollable by humans. We define “meaningful human control” as requiring five properties: comprehensibility, goal modification, behavioral boundaries, decision override, and emergency shutdown capabilities. We then demonstrate through three complementary arguments why this level of control over superintelligence is essentially unattainable. How should we understand the character of the American political present?

How should we understand the character of the American political present? I

I Seamus Heaney was a self-consciously self-made poet. In his essay ‘Feeling into Words’, he gives one of the best accounts available of ‘finding your voice’ as a writer. There were early stirrings of poetry in listening to his mother recite the Latin grammar of her schooldays; the ‘beautiful sprung rhythms’ of the BBC shipping forecast and ‘the litany of the Blessed Virgin that was part of the enforced poetry’ of a Catholic household. He learned to articulate the feelings these induced through reading English poetry at school, and in particular ‘the heavily accented consonantal noise’ of Gerard Manley Hopkins, in whose ‘staccato’ music Heaney heard an encouraging echo of his own ‘energetic, angular’ Ulster accent.

Seamus Heaney was a self-consciously self-made poet. In his essay ‘Feeling into Words’, he gives one of the best accounts available of ‘finding your voice’ as a writer. There were early stirrings of poetry in listening to his mother recite the Latin grammar of her schooldays; the ‘beautiful sprung rhythms’ of the BBC shipping forecast and ‘the litany of the Blessed Virgin that was part of the enforced poetry’ of a Catholic household. He learned to articulate the feelings these induced through reading English poetry at school, and in particular ‘the heavily accented consonantal noise’ of Gerard Manley Hopkins, in whose ‘staccato’ music Heaney heard an encouraging echo of his own ‘energetic, angular’ Ulster accent.