Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

The drone is increasingly regarded as the infantryman’s basic weapon. The U.S. Army is ordering a million drones to equip its soldiers (a war would require many, many times that). Drones are replacing artillery, now having the capability to take out infantry, tanks, artillery, and basically anything else at a fairly long range. Strike drones are supplementing bombers and long-range missiles as a way of dealing damage behind the lines; Ukraine’s drone strikes are degrading Russia’s oil industry from thousands of miles away.

The drone is increasingly regarded as the infantryman’s basic weapon. The U.S. Army is ordering a million drones to equip its soldiers (a war would require many, many times that). Drones are replacing artillery, now having the capability to take out infantry, tanks, artillery, and basically anything else at a fairly long range. Strike drones are supplementing bombers and long-range missiles as a way of dealing damage behind the lines; Ukraine’s drone strikes are degrading Russia’s oil industry from thousands of miles away.

And drone technology is still in its infancy. Currently, drones are still piloted by humans. This makes them subject to electronic warfare that jams the link between pilot and drone, forcing them to use spools of fiber-optic cable to maintain a secure connection. And it means that drone operators have to stay somewhat near the front, exposing them to enemy strikes. Skilled human operators are a valuable resource that limits the amount of drones that can be used at once.

This is about to change.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I

I Jack Kerouac’s only child, Jan Kerouac, lived hard and died young. She was 44 when she succumbed to complications of liver failure in Albuquerque in 1996. She met her famous father, the author of “On the Road” and the avatar of the Beat generation, only twice.

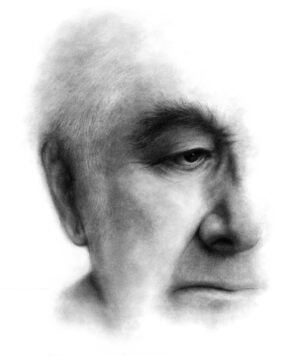

Jack Kerouac’s only child, Jan Kerouac, lived hard and died young. She was 44 when she succumbed to complications of liver failure in Albuquerque in 1996. She met her famous father, the author of “On the Road” and the avatar of the Beat generation, only twice. Now 82, Crumb is America’s greatest cartoonist. Inimitable and inventive as Herriman and Gould were, neither had his range, nor his independence. Crumb, who developed a rounded, cuddly style reminiscent of Depression-era cartoons, is also a great draughtsman, with a capacity to render fastidiously detailed naturalistic drawings. Technique alone cannot account for his eminence, however. Crumb is both an observant satirist and a self-aware student of his own drives. His grasp of American vernacular and his sardonic humour suggest a comparison with Mark Twain as well as with Twain’s admirer, the proudly prejudiced social critic

Now 82, Crumb is America’s greatest cartoonist. Inimitable and inventive as Herriman and Gould were, neither had his range, nor his independence. Crumb, who developed a rounded, cuddly style reminiscent of Depression-era cartoons, is also a great draughtsman, with a capacity to render fastidiously detailed naturalistic drawings. Technique alone cannot account for his eminence, however. Crumb is both an observant satirist and a self-aware student of his own drives. His grasp of American vernacular and his sardonic humour suggest a comparison with Mark Twain as well as with Twain’s admirer, the proudly prejudiced social critic  We are at that strange stage in the adoption curve of a revolutionary technology at which two seemingly contradictory things are true at the same time: It has become clear that artificial intelligence will transform the world. And the technology’s immediate impact is still sufficiently small that it just about remains possible to pretend that this won’t be the case.

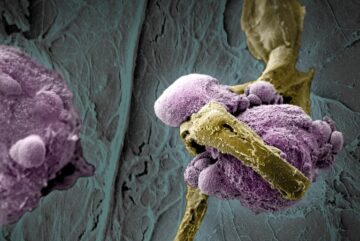

We are at that strange stage in the adoption curve of a revolutionary technology at which two seemingly contradictory things are true at the same time: It has become clear that artificial intelligence will transform the world. And the technology’s immediate impact is still sufficiently small that it just about remains possible to pretend that this won’t be the case. Since the 1800s, cancer surgeons have known that tumours can spread along the nerves. Today, the burgeoning field of cancer neuroscience is starting to reveal the true impact of the disease’s interaction with the nervous system. The phenomenon, known as perineural invasion, is common in certain types of cancer. “When treating patients with head and neck cancers, I see invasion into nerves in about half of cases,” says Moran Amit, professor of head and neck surgery at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. “It’s an ominous feature. It puts patients in a higher risk category and requires us to escalate treatment.”

Since the 1800s, cancer surgeons have known that tumours can spread along the nerves. Today, the burgeoning field of cancer neuroscience is starting to reveal the true impact of the disease’s interaction with the nervous system. The phenomenon, known as perineural invasion, is common in certain types of cancer. “When treating patients with head and neck cancers, I see invasion into nerves in about half of cases,” says Moran Amit, professor of head and neck surgery at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. “It’s an ominous feature. It puts patients in a higher risk category and requires us to escalate treatment.” “The Poems of Seamus Heaney” amplifies a reader’s understanding of the poet’s accomplishment by putting the meticulous grandeur of each book into the context of uncollected and unpublished poems, many of them excellent and all of them illuminating. With a lucid, chronological format for the Contents page, the volume’s editors invite readers to sample the honorable outtakes and preliminaries, the range-finding preparatory studies, that underlie for instance the haunted vision of “North” (1975) or the magisterial yet intimate scope of “Station Island” (1984).

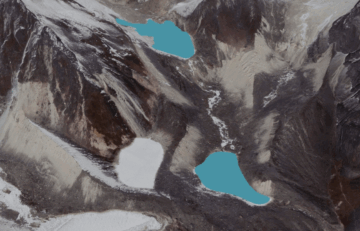

“The Poems of Seamus Heaney” amplifies a reader’s understanding of the poet’s accomplishment by putting the meticulous grandeur of each book into the context of uncollected and unpublished poems, many of them excellent and all of them illuminating. With a lucid, chronological format for the Contents page, the volume’s editors invite readers to sample the honorable outtakes and preliminaries, the range-finding preparatory studies, that underlie for instance the haunted vision of “North” (1975) or the magisterial yet intimate scope of “Station Island” (1984). The ice of the Himalayas is wasting away. Glacier-draped slopes are going bare. The ground atop the mountain range, which sprawls across five Asian countries, is slumping and sliding as the ice beneath it — ice that held the land together — disappears. Meltwater is puddling in the valleys below, forming deep lakes.

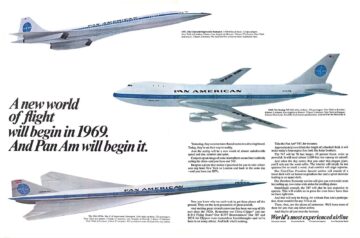

The ice of the Himalayas is wasting away. Glacier-draped slopes are going bare. The ground atop the mountain range, which sprawls across five Asian countries, is slumping and sliding as the ice beneath it — ice that held the land together — disappears. Meltwater is puddling in the valleys below, forming deep lakes. These programs share a common origin: a Cold War-era desire in the West to demonstrate technological superiority over the Soviet Union. Apollo was, of course, championed at the highest levels of the U.S. government and consumed

These programs share a common origin: a Cold War-era desire in the West to demonstrate technological superiority over the Soviet Union. Apollo was, of course, championed at the highest levels of the U.S. government and consumed  It started with the memes. People in the online know were all reading the tweets of Bronze Age Pervert. Quoting from neo-Nietzschean joke-manifesto Bronze Age Mindset was a sign, on what was still in 2016 called the alt-right, that you not only valued strength and masculine vigor and the annihilation of all liberal and feminizing impulses from the sclerosis of the liberal-bureaucratic-democratic establishment but also that you could speak the cant of the scene. It was the first Trump administration, and half the alt-right was high on the promise of meme magic—the tantalizing notion that a group of posters on 4chan had, implausibly, harnessed the latent energies of the universe and the powers of Internet vibes to meme Donald Trump into office. Neopagan vitalism was as sexy, in the recesses of the Internet characterized by avatars of cartoon frogs, as the mirror-image figure of the “resistance witch” on the anti-Trump left.

It started with the memes. People in the online know were all reading the tweets of Bronze Age Pervert. Quoting from neo-Nietzschean joke-manifesto Bronze Age Mindset was a sign, on what was still in 2016 called the alt-right, that you not only valued strength and masculine vigor and the annihilation of all liberal and feminizing impulses from the sclerosis of the liberal-bureaucratic-democratic establishment but also that you could speak the cant of the scene. It was the first Trump administration, and half the alt-right was high on the promise of meme magic—the tantalizing notion that a group of posters on 4chan had, implausibly, harnessed the latent energies of the universe and the powers of Internet vibes to meme Donald Trump into office. Neopagan vitalism was as sexy, in the recesses of the Internet characterized by avatars of cartoon frogs, as the mirror-image figure of the “resistance witch” on the anti-Trump left. The very first sentence of Arabelle Sicardi’s book, The House of

The very first sentence of Arabelle Sicardi’s book, The House of  It’s been a long time since Alice Charton got a good look at a human face. There are plenty of people moving through her world, of course—her husband, her friends, her doctors, her neighbors—but judging just by what she can see, she’d have to take it as an article of faith that any one person was there at all. It was five years ago that the 87-year-old retired schoolteacher, living in a suburb of Paris, first noticed her eyesight failing, with a point in the middle of her field of vision going hazy, muddy, and dim. Soon that point grew into a spot, and the spot into a blotch—until it became impossible for her to recognize people, read a book, or navigate unfamiliar places on the streets.

It’s been a long time since Alice Charton got a good look at a human face. There are plenty of people moving through her world, of course—her husband, her friends, her doctors, her neighbors—but judging just by what she can see, she’d have to take it as an article of faith that any one person was there at all. It was five years ago that the 87-year-old retired schoolteacher, living in a suburb of Paris, first noticed her eyesight failing, with a point in the middle of her field of vision going hazy, muddy, and dim. Soon that point grew into a spot, and the spot into a blotch—until it became impossible for her to recognize people, read a book, or navigate unfamiliar places on the streets. For my money, though, the book is most interesting for those aforementioned moments of tonal whiplash, scenes wherein big shifts of register or reference point are undertaken with remarkably little in the way of narrative scaffolding. Shadow Ticket, in addition to being extremely fun and almost indecently readable, is also replete with edges left conspicuously unsanded, a combination that might go some way toward frustrating or at least reframing the prevailing misconception of Pynchon as a willfully difficult, high-maximalist, paranoid outsider-recluse. It’s a reputation that has obscured a clear view of the author’s work in one form or another for the entirety of a long career, alternately burnishing the image of an enigmatic hipster sage or offering up a strawman for the excesses and overreaches of the showoff tradition he supposedly epitomizes. It’s made the name “Thomas Pynchon” into a byword for inaccessible genius, the Trystero horn into an enduring stall-wall Sharpie tag, and Gravity’s Rainbow into a punchline on The O.C., but, meanwhile, the, you know, actual books? Those have drifted considerably from these mythic calcifications, gradually resolving into a scope and style more characterized by shaggy plotting, political generosity, and out-and-out sweetness than anything resembling the lit-bro hazing rituals that some contemporary readers have been conditioned to expect.

For my money, though, the book is most interesting for those aforementioned moments of tonal whiplash, scenes wherein big shifts of register or reference point are undertaken with remarkably little in the way of narrative scaffolding. Shadow Ticket, in addition to being extremely fun and almost indecently readable, is also replete with edges left conspicuously unsanded, a combination that might go some way toward frustrating or at least reframing the prevailing misconception of Pynchon as a willfully difficult, high-maximalist, paranoid outsider-recluse. It’s a reputation that has obscured a clear view of the author’s work in one form or another for the entirety of a long career, alternately burnishing the image of an enigmatic hipster sage or offering up a strawman for the excesses and overreaches of the showoff tradition he supposedly epitomizes. It’s made the name “Thomas Pynchon” into a byword for inaccessible genius, the Trystero horn into an enduring stall-wall Sharpie tag, and Gravity’s Rainbow into a punchline on The O.C., but, meanwhile, the, you know, actual books? Those have drifted considerably from these mythic calcifications, gradually resolving into a scope and style more characterized by shaggy plotting, political generosity, and out-and-out sweetness than anything resembling the lit-bro hazing rituals that some contemporary readers have been conditioned to expect. What we can see from the last two information crises is that they involve enormous leaps forward in knowledge and understanding, but also a period of intense instability. Following the invention of writing, the world was filled with new, beautiful ideas and new moralities. And there were also new ways to misunderstand each other: the possibility of misreading someone entered the world, as did the possibility of warfare motivated by different interpretations of texts. After the invention of the printing press came the Enlightenment, an explosion of new scientific knowledge and discovery. But before that period, Europe had plunged into the Reformation, which led to the destruction of statues and other artworks and many institutions that had been working at least adequately until then. And, to get to the heart of the matter, the Reformation in Europe meant a lot of people got burned at the stake, or killed in other terrible ways.

What we can see from the last two information crises is that they involve enormous leaps forward in knowledge and understanding, but also a period of intense instability. Following the invention of writing, the world was filled with new, beautiful ideas and new moralities. And there were also new ways to misunderstand each other: the possibility of misreading someone entered the world, as did the possibility of warfare motivated by different interpretations of texts. After the invention of the printing press came the Enlightenment, an explosion of new scientific knowledge and discovery. But before that period, Europe had plunged into the Reformation, which led to the destruction of statues and other artworks and many institutions that had been working at least adequately until then. And, to get to the heart of the matter, the Reformation in Europe meant a lot of people got burned at the stake, or killed in other terrible ways.