Jason Horowitz in The New York Times:

Most members of the band subscribed to a live-fast-die-young lifestyle. But as they partook in the drinking and drugging endemic to the 1990s grunge scene after shows at the Whiskey a Go Go, Roxy and other West Coast clubs, the band’s guitarist, Valter Longo, a nutrition-obsessed Italian Ph.D. student, wrestled with a lifelong addiction to longevity.

Most members of the band subscribed to a live-fast-die-young lifestyle. But as they partook in the drinking and drugging endemic to the 1990s grunge scene after shows at the Whiskey a Go Go, Roxy and other West Coast clubs, the band’s guitarist, Valter Longo, a nutrition-obsessed Italian Ph.D. student, wrestled with a lifelong addiction to longevity.

Now, decades after Dr. Longo dropped his grunge-era band, DOT, for a career in biochemistry, the Italian professor stands with his floppy rocker hair and lab coat at the nexus of Italy’s eating and aging obsessions. “For studying aging, Italy is just incredible,” said Dr. Longo, a youthful 56, at the lab he runs at a cancer institute in Milan, where he will speak at an aging conference later this month. Italy has one of the world’s oldest populations, including multiple pockets of centenarians who tantalize researchers searching for the fountain of youth. “It’s nirvana.” Dr. Longo, who is also a professor of gerontology and director of the U.S.C. Longevity Institute in California, has long advocated longer and better living through eating Lite Italian, one of a global explosion of Road to Perpetual Wellville theories about how to stay young in a field that is itself still in its adolescence.

More here.

Economics has achieved much; there are large bodies of often nonobvious theoretical understandings and of careful and sometimes compelling empirical evidence. The profession knows and understands many things. Yet today we are in some disarray. We did not collectively predict the financial crisis and, worse still, we may have contributed to it through an overenthusiastic belief in the efficacy of markets, especially financial markets whose structure and implications we understood less well than we thought. Recent macroeconomic events, admittedly unusual, have seen quarrelling experts whose main point of agreement is the incorrectness of others. Economics Nobel Prize winners have been known to denounce each other’s work at the ceremonies in Stockholm, much to the consternation of those laureates in the sciences who believe that prizes are given for getting things right.

Economics has achieved much; there are large bodies of often nonobvious theoretical understandings and of careful and sometimes compelling empirical evidence. The profession knows and understands many things. Yet today we are in some disarray. We did not collectively predict the financial crisis and, worse still, we may have contributed to it through an overenthusiastic belief in the efficacy of markets, especially financial markets whose structure and implications we understood less well than we thought. Recent macroeconomic events, admittedly unusual, have seen quarrelling experts whose main point of agreement is the incorrectness of others. Economics Nobel Prize winners have been known to denounce each other’s work at the ceremonies in Stockholm, much to the consternation of those laureates in the sciences who believe that prizes are given for getting things right. Frans de Waal, one of the world’s preeminent primatologists, passed away on 14 March 2024, at the age of 75. He was the Charles Howard Candler Professor Emeritus of Psychology and former director of the Living Links Center for the Advanced Study of Ape and Human Evolution at the Emory National Primate Research Center.

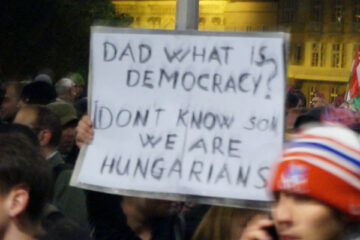

Frans de Waal, one of the world’s preeminent primatologists, passed away on 14 March 2024, at the age of 75. He was the Charles Howard Candler Professor Emeritus of Psychology and former director of the Living Links Center for the Advanced Study of Ape and Human Evolution at the Emory National Primate Research Center. Last September an article on the front page of a leading Hungarian daily began, “The story of the ever-deepening refugee crisis is taking ever more unexpected turns.” A prominent Hungarian intellectual and former dissident, György Konrád, had come out in support of the efforts of the Hungarian government to build a wall to keep out newcomers and to cast them as economic opportunists rather than political refugees. In another corner of the Hungarian media, pundits were citing passages from The Final Tavern (A végső kocsma), a 2014 book by Holocaust survivor and 2002 Nobel laureate Imre Kertész, who passed away last month. In the book, Kertész was sharply critical of liberals’ welcoming attitude toward Muslim refugees and migrants. His and Konrád’s statements were registered with incredulity in the liberal press and with undisguised relish on the right.

Last September an article on the front page of a leading Hungarian daily began, “The story of the ever-deepening refugee crisis is taking ever more unexpected turns.” A prominent Hungarian intellectual and former dissident, György Konrád, had come out in support of the efforts of the Hungarian government to build a wall to keep out newcomers and to cast them as economic opportunists rather than political refugees. In another corner of the Hungarian media, pundits were citing passages from The Final Tavern (A végső kocsma), a 2014 book by Holocaust survivor and 2002 Nobel laureate Imre Kertész, who passed away last month. In the book, Kertész was sharply critical of liberals’ welcoming attitude toward Muslim refugees and migrants. His and Konrád’s statements were registered with incredulity in the liberal press and with undisguised relish on the right. Back in December 2016, I was sitting in my office at the World Bank in Washington, D.C., feeling unmoored and disheartened. Every day, I walked through Lafayette Park in front of the White House to get to my work. But lately, the noise had been so loud and ugly about the Muslim ban and building a wall. I was beginning to panic. What’s a person like me even supposed to do about this? Why am I even here?

Back in December 2016, I was sitting in my office at the World Bank in Washington, D.C., feeling unmoored and disheartened. Every day, I walked through Lafayette Park in front of the White House to get to my work. But lately, the noise had been so loud and ugly about the Muslim ban and building a wall. I was beginning to panic. What’s a person like me even supposed to do about this? Why am I even here? In one way or another, the superrich have always been trying to extend their lives. Ancient Egyptians crammed their tombs with everything they’d need to live on in an afterlife not unlike their own world, just filled with more fun. In the modern era, the ultra-wealthy have attempted to live on through their legacies: sponsoring museums and galleries to immortalize their names.

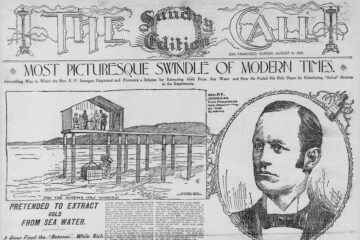

In one way or another, the superrich have always been trying to extend their lives. Ancient Egyptians crammed their tombs with everything they’d need to live on in an afterlife not unlike their own world, just filled with more fun. In the modern era, the ultra-wealthy have attempted to live on through their legacies: sponsoring museums and galleries to immortalize their names. CRAP paper accepted by journal

CRAP paper accepted by journal Bright, impetuous and obsessed with beautiful things, Isabella Stewart Gardner led a life out of a Gilded Age novel. Born into a wealthy New York family, she married into an even wealthier Boston one when she wed John Lowell Gardner in 1860, only to be ostracized by her adopted city’s more conservative denizens, who found her self-assurance and penchant for “jollification” a bit much.

Bright, impetuous and obsessed with beautiful things, Isabella Stewart Gardner led a life out of a Gilded Age novel. Born into a wealthy New York family, she married into an even wealthier Boston one when she wed John Lowell Gardner in 1860, only to be ostracized by her adopted city’s more conservative denizens, who found her self-assurance and penchant for “jollification” a bit much. The world can be impatient with slow writers. Nearly a decade after Jeffrey Eugenides published

The world can be impatient with slow writers. Nearly a decade after Jeffrey Eugenides published  Kevin Hart insists he’s never written a joke.

Kevin Hart insists he’s never written a joke.