Tim Sahay in Polycrisis:

Protests led by farmers have been roiling Europe for months. In Belgium, Germany, Romania, the Netherlands, Poland, and France, farmers—armed with grievances ranging from subsidized Ukrainian grain imports to the EU-Mercosur trade deal and falling prices—have been taking to the streets, blocking traffic, and pelting the European parliament with eggs.

In the European halls of power, right-wing parties are taking note. In the Netherlands, populist and conservative parties have protested the ammonia tax imposed on the nation’s livestock. In Italy, figures in the ruling hard-right League and Brothers of Italy coalition have denounced EU decarbonization policies as hurting both consumers and industries. In France, Marine Le Pen, who ran for president as the National Rally candidate in the last election, is fighting against diesel taxes and for greater energy subsidies. The crystallization of a robust anti-climate coalition in the European Parliament is a real possibility after elections in June.

The farmers’ protests are a powerful reminder that the challenge to achieve “net zero” isn’t simply a technical one, but a political one. Unable to form or mobilize coalitions with working and middle classes, parties of the left have been locked out of power in much of the continent. Meanwhile, fossil-fuel interests have mobilized cross-class coalitions for militarized adaptation.

The socioeconomic risks of rebellion are not lost on incumbent governments in the global North and South. In the energy crisis of 2022–2023, European governments chose to cut fuel taxes and subsidize citizens’ energy bills on an enormous scale. Southern governments, for their part, continue to resist IMF’s consistent policy advice that they should stop supporting their populations with fossil-fuel, food, and agricultural subsidies.

Why is it so hard to stitch together a cross-class coalition for climate policy?

More here.

Voisin is a senior researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research in Paris. There, she studies algebraic varieties, which can be thought of as shapes defined by sets of polynomial equations, the way a circle is defined by the polynomial x2 + y2 = 1. She is one of the world’s foremost experts in Hodge theory, a toolkit that mathematicians use to study key properties of algebraic varieties.

Voisin is a senior researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research in Paris. There, she studies algebraic varieties, which can be thought of as shapes defined by sets of polynomial equations, the way a circle is defined by the polynomial x2 + y2 = 1. She is one of the world’s foremost experts in Hodge theory, a toolkit that mathematicians use to study key properties of algebraic varieties.

Imagine you’re a middle-class, middle-aged mom in any number of American suburbs outside Atlanta, Philadelphia, Detroit, or Phoenix—the kind of civic-minded, active voter that both parties chase every election.

Imagine you’re a middle-class, middle-aged mom in any number of American suburbs outside Atlanta, Philadelphia, Detroit, or Phoenix—the kind of civic-minded, active voter that both parties chase every election. As an anthropologist, this intimacy with cats fascinates me because they represent another instance of how “human culture” is in fact made up of our relationships with nonhumans. Globally, cats have accompanied humans since ancient times, beginning in

As an anthropologist, this intimacy with cats fascinates me because they represent another instance of how “human culture” is in fact made up of our relationships with nonhumans. Globally, cats have accompanied humans since ancient times, beginning in  Rihanna, Mark Zuckerberg, bejeweled elephants and 5,500 drones. Those were some of the highlights of what is likely the most ostentatious “pre-wedding” ceremony the modern world has ever seen.

Rihanna, Mark Zuckerberg, bejeweled elephants and 5,500 drones. Those were some of the highlights of what is likely the most ostentatious “pre-wedding” ceremony the modern world has ever seen. I

I When I was editing my debut novel,

When I was editing my debut novel,  “Indelible in the hippocampus is the laughter.”

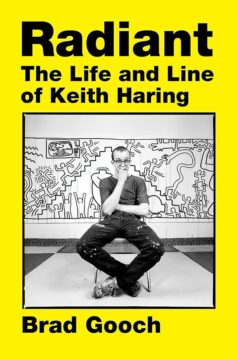

“Indelible in the hippocampus is the laughter.” While modern audiences might be more likely to understand the import of these themes, many critics at the time discounted Haring’s work as “fast food,” as one put it, adding, “It’s a good time, it’s boogieing on a Saturday night, it’s alive, but great, no.” One curator blamed Haring’s commercial appeal for the reluctance to take his art seriously, saying, “I think Haring was so successful that other artists could not forgive him.” Gallerist Jeffrey Deitch pointed out that most artists enjoying Haring’s level of financial success would have been churning out even more sellable work. But Haring was committed to public projects such as murals, which he did for little or no compensation.

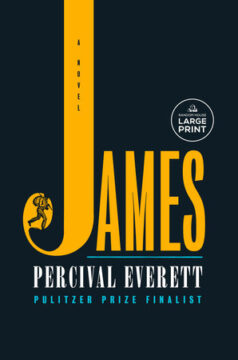

While modern audiences might be more likely to understand the import of these themes, many critics at the time discounted Haring’s work as “fast food,” as one put it, adding, “It’s a good time, it’s boogieing on a Saturday night, it’s alive, but great, no.” One curator blamed Haring’s commercial appeal for the reluctance to take his art seriously, saying, “I think Haring was so successful that other artists could not forgive him.” Gallerist Jeffrey Deitch pointed out that most artists enjoying Haring’s level of financial success would have been churning out even more sellable work. But Haring was committed to public projects such as murals, which he did for little or no compensation. Everett mostly sticks to the broad outlines of Twain’s novel. He is riding the same currents; the book flows inexorably, like a river, yet its short chapters keep the movement swift. James is on the run, of course, because he has learned that Miss Watson plans to sell him to a man in New Orleans. He will be separated from his wife and children. Huck is on the run because he has faked his own death after being beaten by his father. They find each other on an island in the Mississippi, and their flight begins. The reader slowly discovers that their bonds run deeper than friendship.

Everett mostly sticks to the broad outlines of Twain’s novel. He is riding the same currents; the book flows inexorably, like a river, yet its short chapters keep the movement swift. James is on the run, of course, because he has learned that Miss Watson plans to sell him to a man in New Orleans. He will be separated from his wife and children. Huck is on the run because he has faked his own death after being beaten by his father. They find each other on an island in the Mississippi, and their flight begins. The reader slowly discovers that their bonds run deeper than friendship. I was sitting on a train, travelling from my home in Poughkeepsie to New York City, when I saw a note on my phone asking me to write the piece below. I began thinking of a painting, a portrait of his father painted by the Indian artist Atul Dodiya, but the other memory that came to me was that I had long ago been sitting in the same Metro North train bound for New York City when the idea for my new novel,

I was sitting on a train, travelling from my home in Poughkeepsie to New York City, when I saw a note on my phone asking me to write the piece below. I began thinking of a painting, a portrait of his father painted by the Indian artist Atul Dodiya, but the other memory that came to me was that I had long ago been sitting in the same Metro North train bound for New York City when the idea for my new novel,