Matt Fuchs in Time:

Maybe you heard somewhere that pickles are a “superfood,” and dutifully added them to your shopping list. Unfortunately, you may reach for the wrong jar, because many pickles at supermarkets aren’t especially good for you. Scientists have made progress in separating fact from fiction when it comes to health claims about pickles: both the cucumber kind, and other types of pickled vegetables. We asked experts how to find the healthiest kinds of pickles, which benefits are backed by research, and the right amount to eat every day.

Maybe you heard somewhere that pickles are a “superfood,” and dutifully added them to your shopping list. Unfortunately, you may reach for the wrong jar, because many pickles at supermarkets aren’t especially good for you. Scientists have made progress in separating fact from fiction when it comes to health claims about pickles: both the cucumber kind, and other types of pickled vegetables. We asked experts how to find the healthiest kinds of pickles, which benefits are backed by research, and the right amount to eat every day.

…More research is needed, but a few dozen studies have been well designed to compare diets with pickled vegetables to diets with non-pickled versions of the same vegetables, Hutkins says. Most of this research has been conducted in Korea and focuses on kimchi, or pickled cabbage—not pickled cucumbers. But the findings are promising, with fermented vegetables—again, mostly cabbage—linked to significantly better glucose metabolism, lower risk of Type 2 diabetes, a more robust immune system, decreased triglyceride levels, and higher HDL cholesterol (the good kind) in people who ate them.

More here.

You might think you remember taking a trip to Disneyland when you were 18 months old, or that time you had chickenpox when you were 2—but you almost certainly don’t. However real they may seem, your earliest treasured memories were probably implanted by seeing photos or hearing your parents’ stories about waiting in line for the spinning teacups. Recalling those manufactured memories again and again consolidated them in your brain, making them as vivid as your last summer vacation.

You might think you remember taking a trip to Disneyland when you were 18 months old, or that time you had chickenpox when you were 2—but you almost certainly don’t. However real they may seem, your earliest treasured memories were probably implanted by seeing photos or hearing your parents’ stories about waiting in line for the spinning teacups. Recalling those manufactured memories again and again consolidated them in your brain, making them as vivid as your last summer vacation. Gabo, as he is affectionately known by his fans, had the kind of impact that only a handful of artists in any century, in any genre, have ever achieved. No one better dramatized First World realism’s inability to cope with Third World reality (or coloniality’s spectrality) than García Márquez. No one better strategized how those of us hailing from what is euphemistically called the Global South might capture our impossible realities, or meaningfully intervene in imperial struggle between the true and the real.

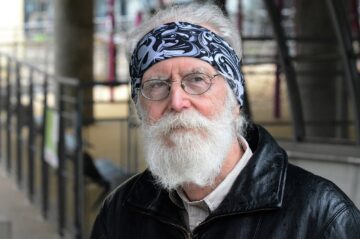

Gabo, as he is affectionately known by his fans, had the kind of impact that only a handful of artists in any century, in any genre, have ever achieved. No one better dramatized First World realism’s inability to cope with Third World reality (or coloniality’s spectrality) than García Márquez. No one better strategized how those of us hailing from what is euphemistically called the Global South might capture our impossible realities, or meaningfully intervene in imperial struggle between the true and the real. As a 15-year-old, a month in the hospital helped spur his mathematical abilities. A decade earlier, he had gone blind in his right eye after the retina detached, the result of a genetic condition. Then the retina in his left eye detached too. His father, a college math instructor, taught him mathematics while his eyes were bandaged.

As a 15-year-old, a month in the hospital helped spur his mathematical abilities. A decade earlier, he had gone blind in his right eye after the retina detached, the result of a genetic condition. Then the retina in his left eye detached too. His father, a college math instructor, taught him mathematics while his eyes were bandaged. India’s recent economic success, solid momentum, and promising prospects are making the country ever more influential both regionally and internationally. But the experience of other countries – most notably China over the last three decades – suggests that such rapid influence and robust progress can be tricky to manage. After all, an action that makes sense domestically may conflict with what other countries expect from a systemically important economy. By the same token, actions that make sense internationally could complicate domestic economic progress.

India’s recent economic success, solid momentum, and promising prospects are making the country ever more influential both regionally and internationally. But the experience of other countries – most notably China over the last three decades – suggests that such rapid influence and robust progress can be tricky to manage. After all, an action that makes sense domestically may conflict with what other countries expect from a systemically important economy. By the same token, actions that make sense internationally could complicate domestic economic progress. O

O In May 1606, Caravaggio’s rackety life caught up with him. He already had a long list of misdemeanours against his name. He had been twice arrested for carrying a sword without a permit; put on trial by the Roman authorities for writing scurrilous verses about a rival, Giovanni Baglione (or “Johnny Bollocks” according to the poems); arrested for affray and assault, in one incident being injured himself (his testimony to the police survives: “I wounded myself with my own sword when I fell down these stairs. I don’t know where it was and there was no one else there”); arrested again for smashing a plate of artichokes in the face of a waiter; for throwing stones and abusing a constable (telling him he could “stick [his sword] up his arse”); and for smearing excrement on the house of the landlady who had had his belongings seized in payment of missed rent. There were more incidents, all meticulously recorded in the Roman archives.

In May 1606, Caravaggio’s rackety life caught up with him. He already had a long list of misdemeanours against his name. He had been twice arrested for carrying a sword without a permit; put on trial by the Roman authorities for writing scurrilous verses about a rival, Giovanni Baglione (or “Johnny Bollocks” according to the poems); arrested for affray and assault, in one incident being injured himself (his testimony to the police survives: “I wounded myself with my own sword when I fell down these stairs. I don’t know where it was and there was no one else there”); arrested again for smashing a plate of artichokes in the face of a waiter; for throwing stones and abusing a constable (telling him he could “stick [his sword] up his arse”); and for smearing excrement on the house of the landlady who had had his belongings seized in payment of missed rent. There were more incidents, all meticulously recorded in the Roman archives. In February 1995, New York Governor George Pataki announced plans to close the Willard Asylum for the Insane, a state-run institution that opened in 1869 on the eastern shore of Seneca Lake. Portions of the hospital would be converted into a drug treatment center for prisoners; the rest would be permanently shuttered. Before this could happen, however, the hospital’s many artifacts—for example, its 19th-century medical equipmenat—needed to be documented and preserved. This is what Craig Williams, then a curator at the New York State Museum in Albany, did for much of the spring of 1995. One morning that April, Beverly Courtwright, a longtime storehouse clerk at Willard, told Williams that he needed to see something. She took him to the deteriorated brick structure that once housed Willard’s medical labs and occupational therapy rooms. Together they went up several flights of stairs to the attic, an open loft with exposed wood rafters and a brick wall at one end. In the brick wall was a door. Courtwright didn’t open it, so Williams went through alone.

In February 1995, New York Governor George Pataki announced plans to close the Willard Asylum for the Insane, a state-run institution that opened in 1869 on the eastern shore of Seneca Lake. Portions of the hospital would be converted into a drug treatment center for prisoners; the rest would be permanently shuttered. Before this could happen, however, the hospital’s many artifacts—for example, its 19th-century medical equipmenat—needed to be documented and preserved. This is what Craig Williams, then a curator at the New York State Museum in Albany, did for much of the spring of 1995. One morning that April, Beverly Courtwright, a longtime storehouse clerk at Willard, told Williams that he needed to see something. She took him to the deteriorated brick structure that once housed Willard’s medical labs and occupational therapy rooms. Together they went up several flights of stairs to the attic, an open loft with exposed wood rafters and a brick wall at one end. In the brick wall was a door. Courtwright didn’t open it, so Williams went through alone. The discovery of animals around hydrothermal vents has led to a dramatic broadening of our understanding of the sorts of environments in which life can survive. This has significant implications for the search for extraterrestrial life – if life thrives in such environments on Earth, it is plausible it might flourish in similar conditions in the oceans of ice moons such as Enceladus, which orbits Saturn. It has also shifted assumptions about where life on Earth began: perhaps it was not in a shallow pool, but somewhere in the depths of the primordial sea. In other words, the deep ocean might not be a place of death and forgetting, but rather the birthplace of life on our planet.

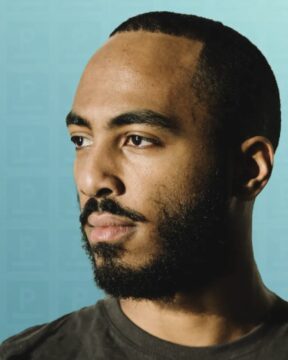

The discovery of animals around hydrothermal vents has led to a dramatic broadening of our understanding of the sorts of environments in which life can survive. This has significant implications for the search for extraterrestrial life – if life thrives in such environments on Earth, it is plausible it might flourish in similar conditions in the oceans of ice moons such as Enceladus, which orbits Saturn. It has also shifted assumptions about where life on Earth began: perhaps it was not in a shallow pool, but somewhere in the depths of the primordial sea. In other words, the deep ocean might not be a place of death and forgetting, but rather the birthplace of life on our planet. Coleman Hughes: I think there’s a lot of people that might agree with some points I make about the prevalence of racism, the decline of racism, but they might think, “Well, what’s the harm in exaggerating racism a little bit? I can see the harm in under-exaggerating racism, but shouldn’t we err on the side of assuming that there’s more racism and white supremacy out there so that we’re really facing the problem?” And I wanted to highlight the fact that there is a potential harm, including to black people, but people of color in general, to exaggerating racism.

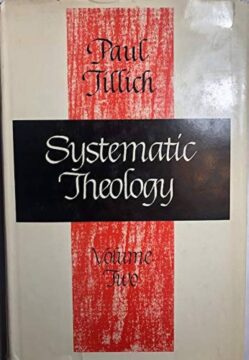

Coleman Hughes: I think there’s a lot of people that might agree with some points I make about the prevalence of racism, the decline of racism, but they might think, “Well, what’s the harm in exaggerating racism a little bit? I can see the harm in under-exaggerating racism, but shouldn’t we err on the side of assuming that there’s more racism and white supremacy out there so that we’re really facing the problem?” And I wanted to highlight the fact that there is a potential harm, including to black people, but people of color in general, to exaggerating racism. The Latin renders to “who is blessed for ever” and concludes an enigmatic, brief paragraph. First published in 1294, La Vita Nuova is a tantalizing prelude to the Florentine poet’s masterpiece, La Commedia, known today as The Divine Comedy. For centuries, readers and scholars have pored over La Vita Nuova (Italian for, literally, the new life)—convinced, as we often are, that a gifted writer’s nascent work contains the answers to longstanding mysteries.

The Latin renders to “who is blessed for ever” and concludes an enigmatic, brief paragraph. First published in 1294, La Vita Nuova is a tantalizing prelude to the Florentine poet’s masterpiece, La Commedia, known today as The Divine Comedy. For centuries, readers and scholars have pored over La Vita Nuova (Italian for, literally, the new life)—convinced, as we often are, that a gifted writer’s nascent work contains the answers to longstanding mysteries. According to some estimates, consumers spend $62 billion a year on “anti-aging” treatments. But while creams, hair dyes and Botox can give the impression of youth, none of them can roll back the hands of time.

According to some estimates, consumers spend $62 billion a year on “anti-aging” treatments. But while creams, hair dyes and Botox can give the impression of youth, none of them can roll back the hands of time. This photograph is the kind of photograph you’d throw away. If you’re working with a digital camera, you would immediately delete it. It’s a disaster. Trash it and move on. There’s a big metal bar in the middle of the shot. It must be from a gate or something. The metal bar not only dominates the very center of the picture, it’s also so close to the camera that the bar is blurred at the top. Technically speaking, that is a no-no. This is a terrible photograph.

This photograph is the kind of photograph you’d throw away. If you’re working with a digital camera, you would immediately delete it. It’s a disaster. Trash it and move on. There’s a big metal bar in the middle of the shot. It must be from a gate or something. The metal bar not only dominates the very center of the picture, it’s also so close to the camera that the bar is blurred at the top. Technically speaking, that is a no-no. This is a terrible photograph.