Jennifer Szalai in The New York Times:

One of the most arresting things about Adam Phillips’s work is how it resists easy summary, dissolving into a trace memory the moment you try to describe it. Over several decades, in more than 20 books — many of them slim volumes further subdivided into even slimmer essays — Phillips, a British psychoanalyst, sidles up to his subjects, preferring the gentle mode of suggestion to the blunt force of argument. His writing has a way of sneaking up on you, like a subterranean force. An interviewer once described trying to edit his comments as “sculpting with lava.”

One of the most arresting things about Adam Phillips’s work is how it resists easy summary, dissolving into a trace memory the moment you try to describe it. Over several decades, in more than 20 books — many of them slim volumes further subdivided into even slimmer essays — Phillips, a British psychoanalyst, sidles up to his subjects, preferring the gentle mode of suggestion to the blunt force of argument. His writing has a way of sneaking up on you, like a subterranean force. An interviewer once described trying to edit his comments as “sculpting with lava.”

Even Phillips’s titles tell us only so much. “Attention Seeking” (2019) sounds as if it’s about something shameful, when in fact, he says, “attention-seeking is one of the best things we do.” In “On Wanting to Change” (2021), he writes about change as an object of both desire and dread; we long for the conclusiveness of a conversion experience, “a change that will finally put a stop to the need for change.”

Phillips, who was formerly a child psychotherapist, likes to play with terms that are capacious, elastic and stubbornly ambiguous. The title of his new book, “On Giving Up,” covers the vast territory between hope and despair. We can give up smoking, sugar or a bad habit; but we can also give up on ourselves. “We give things up when we believe we can change; we give up when we believe we can’t.”

More here.

Tenen, a tenured professor of English at New York’s Columbia University, isn’t nearly as apocalyptic as he initially makes out. His is an oddly titled book – do robots need literary theory? Are we the robots? – that has little in common with the techno-theory of writers such as

Tenen, a tenured professor of English at New York’s Columbia University, isn’t nearly as apocalyptic as he initially makes out. His is an oddly titled book – do robots need literary theory? Are we the robots? – that has little in common with the techno-theory of writers such as  It is possible to imagine the jazz musician Sonny Rollins’s life as a novel, pitched between realism and surrealism in the manner of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man.” The settings would include Harlem, where Rollins grew up poor in the 1930s and ’40s, and the decadence of clubland in New York City and Chicago at the century’s midpoint, when he was a musical prodigy. A chapter might linger on the recording of his landmark 1957 album “Saxophone Colossus.”

It is possible to imagine the jazz musician Sonny Rollins’s life as a novel, pitched between realism and surrealism in the manner of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man.” The settings would include Harlem, where Rollins grew up poor in the 1930s and ’40s, and the decadence of clubland in New York City and Chicago at the century’s midpoint, when he was a musical prodigy. A chapter might linger on the recording of his landmark 1957 album “Saxophone Colossus.” One of the most celebrated lines from Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita emerges from the lips of the devil himself. “Manuscripts don’t burn,” Woland, the mysterious Professor of Black Magic, tells the eponymous Master. The declaration echoes throughout the narrative: try as the Soviet authorities might, they cannot ban, repress, or destroy the Master’s art, because the unyielding ideas within have taken on a life of their own.

One of the most celebrated lines from Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita emerges from the lips of the devil himself. “Manuscripts don’t burn,” Woland, the mysterious Professor of Black Magic, tells the eponymous Master. The declaration echoes throughout the narrative: try as the Soviet authorities might, they cannot ban, repress, or destroy the Master’s art, because the unyielding ideas within have taken on a life of their own. O

O

In my second year of college I applied for a spot in a creative writing program. If I got in, I could graduate in two years with a writing major. If I didn’t, well, I needed a new major. I fussed over the application for months. Attended info sessions, met with the program director, revised my portfolio of poems so often that one professor finally said, Bryan, relax. Let the poems speak. I didn’t grow up saying I wanted to be a writer, but the signs were there, like a secret wish I kept from everyone, myself included. A stroll through the half-hearted journals and failed diaries of my teenage years turns up observations like: “I want to write books, but you can’t make a living that way.” Such a Midwesterner: The arts just aren’t practical.

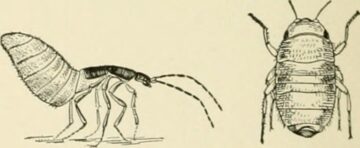

In my second year of college I applied for a spot in a creative writing program. If I got in, I could graduate in two years with a writing major. If I didn’t, well, I needed a new major. I fussed over the application for months. Attended info sessions, met with the program director, revised my portfolio of poems so often that one professor finally said, Bryan, relax. Let the poems speak. I didn’t grow up saying I wanted to be a writer, but the signs were there, like a secret wish I kept from everyone, myself included. A stroll through the half-hearted journals and failed diaries of my teenage years turns up observations like: “I want to write books, but you can’t make a living that way.” Such a Midwesterner: The arts just aren’t practical. However, a growing collection of new experiments is challenging the old consensus. Far from being six-legged automatons, they can experience feelings akin to pain and suffering, joy and desire. When Chittka gave bumblebees an extra jolt of sucrose, their favorite food, the bees

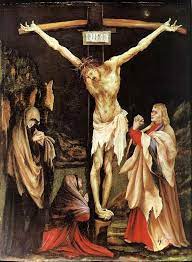

However, a growing collection of new experiments is challenging the old consensus. Far from being six-legged automatons, they can experience feelings akin to pain and suffering, joy and desire. When Chittka gave bumblebees an extra jolt of sucrose, their favorite food, the bees  Though firmly a Renaissance painter in regard to technical acumen, Grünewald was Medieval in his vision, an inheritor of the 14th and 15th centuries’ comfort with the horrors of embodiment. In Germany, in particular, there existed then a form of devotion that took succor precisely in visualizing the sort of gruesome tableaux that Grünewald expertly painted, especially as regards the paradox of an almighty God himself suffering and dying. “Be assured of this,” wrote Suso’s contemporary, the mystic Thomas à Kempis in

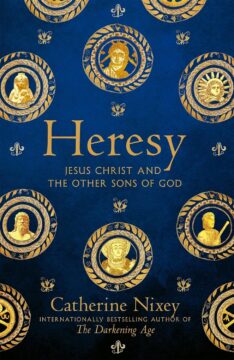

Though firmly a Renaissance painter in regard to technical acumen, Grünewald was Medieval in his vision, an inheritor of the 14th and 15th centuries’ comfort with the horrors of embodiment. In Germany, in particular, there existed then a form of devotion that took succor precisely in visualizing the sort of gruesome tableaux that Grünewald expertly painted, especially as regards the paradox of an almighty God himself suffering and dying. “Be assured of this,” wrote Suso’s contemporary, the mystic Thomas à Kempis in  There were “many Jesuses, many Christs – many of them unimaginably strange to us today” – alongside other magi who resembled some of these Christs. Sometimes Jesus had a physical body; at others he was an apparition that left no footprints. There was a Jesus who warned his disciples against “filthy intercourse” and instructed them never to have children. In one account, an angry young Jesus curses a small boy, who becomes withered and deformed; later Jesus curses another boy, who falls down dead. There were Jesuses that hung in agony on the cross, and others who suffered no pain. In addition to diverse Jesuses, there was Apollonius, a first-century Greek philosopher and miracle-worker, sometimes called “the pagan Christ”.

There were “many Jesuses, many Christs – many of them unimaginably strange to us today” – alongside other magi who resembled some of these Christs. Sometimes Jesus had a physical body; at others he was an apparition that left no footprints. There was a Jesus who warned his disciples against “filthy intercourse” and instructed them never to have children. In one account, an angry young Jesus curses a small boy, who becomes withered and deformed; later Jesus curses another boy, who falls down dead. There were Jesuses that hung in agony on the cross, and others who suffered no pain. In addition to diverse Jesuses, there was Apollonius, a first-century Greek philosopher and miracle-worker, sometimes called “the pagan Christ”. Say you’re at a party with nine other people and everyone shakes everyone else’s hand exactly once. How many handshakes take place?

Say you’re at a party with nine other people and everyone shakes everyone else’s hand exactly once. How many handshakes take place?