Raja Menon in the Boston Review:

On Friday, March 22, gunmen toting assault rifles stormed Crocus City Hall, west of Moscow in the Krasnogorsk district, shot the guards and, as graphic videos show, opened fire on the concert audience without restraint. More than 6,000 tickets had been sold for the performance by the famed Russian rock band Piknik. At least 137 people were killed and many more wounded, some critically; the final death tally could be higher. That even more people were not shot may owe to the perpetrators’ plan to decamp before Russian security forces arrived on the scene. In a move that seemed calculated to maximize the terror, generate publicity, and broadcast the Russian government’s ineptitude, the assailants set parts of the building ablaze. According to some reports, 90 minutes elapsed before Russian special forces arrived. Putin waited until Saturday afternoon before addressing the Russian people in a televised address. By then, an offshoot of the Islamic State, Islamic State–Khorasan (IS-K), had already claimed responsibility.

On Friday, March 22, gunmen toting assault rifles stormed Crocus City Hall, west of Moscow in the Krasnogorsk district, shot the guards and, as graphic videos show, opened fire on the concert audience without restraint. More than 6,000 tickets had been sold for the performance by the famed Russian rock band Piknik. At least 137 people were killed and many more wounded, some critically; the final death tally could be higher. That even more people were not shot may owe to the perpetrators’ plan to decamp before Russian security forces arrived on the scene. In a move that seemed calculated to maximize the terror, generate publicity, and broadcast the Russian government’s ineptitude, the assailants set parts of the building ablaze. According to some reports, 90 minutes elapsed before Russian special forces arrived. Putin waited until Saturday afternoon before addressing the Russian people in a televised address. By then, an offshoot of the Islamic State, Islamic State–Khorasan (IS-K), had already claimed responsibility.

The attack reverberated through Russian society, but also rattled the government, which was caught unaware and unprepared. For Putin, the attack came at a particularly bad time.

More here.

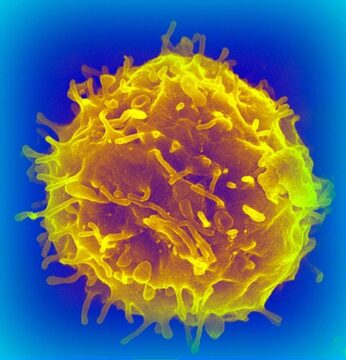

Old mice developed more youthful immune systems after scientists reduced aberrant

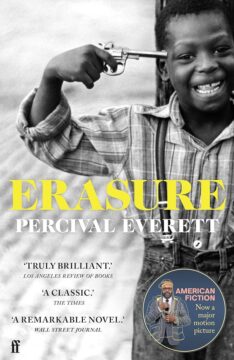

Old mice developed more youthful immune systems after scientists reduced aberrant  “I FOUND IT extremely honest, forthright, and moving in ways I had not expected it to be,” Toni Morrison wrote to an aspiring novelist in 1977, “but it is a shuddering book and one that offers no escape for any reader whatsoever.” Still, Morrison, then a senior editor at Random House, liked the manuscript so much that, before responding, she passed it around the office to drum up support. The verdict was “intelligent,” but also “very ‘down,’ depressing, spiritually abrasive.” Whatever the merits of the writing, Morrison’s colleagues predicted, the potent mix of dissatisfaction, anger, and mournfulness would limit the book’s commercial appeal—and Morrison reluctantly agreed. “You don’t want to escape and I don’t want to escape,” her letter concludes, “but perhaps the public does and perhaps we are in the business of helping them do that.”

“I FOUND IT extremely honest, forthright, and moving in ways I had not expected it to be,” Toni Morrison wrote to an aspiring novelist in 1977, “but it is a shuddering book and one that offers no escape for any reader whatsoever.” Still, Morrison, then a senior editor at Random House, liked the manuscript so much that, before responding, she passed it around the office to drum up support. The verdict was “intelligent,” but also “very ‘down,’ depressing, spiritually abrasive.” Whatever the merits of the writing, Morrison’s colleagues predicted, the potent mix of dissatisfaction, anger, and mournfulness would limit the book’s commercial appeal—and Morrison reluctantly agreed. “You don’t want to escape and I don’t want to escape,” her letter concludes, “but perhaps the public does and perhaps we are in the business of helping them do that.”

I

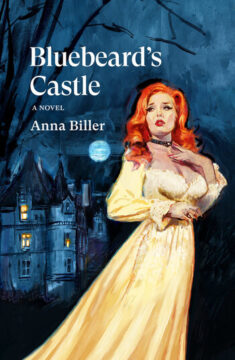

I FILMMAKER ANNA BILLER begins her debut novel, Bluebeard’s Castle, with a warning: “Some husbands,” she writes, “are pussycats, some are dullards or harmless rogues, and some are Bluebeards.” Folklore and literary history are full of Bluebeards: Charles Perrault’s original fairy tale, two Brothers Grimm versions, Jane Eyre’s Mr. Rochester, modern retellings by writers, composers, and directors ranging from Georges Méliès and Béla Bartók to Helen Oyeyemi and Catherine Breillat. The elements of the story remain essentially the same: a young woman marries a mysterious, wealthy widower. Despite warnings (sometimes from her husband, sometimes from outsiders), she explores the recesses of his house and discovers that he has murdered all his former wives and keeps their bodies in a hidden chamber. The intrepid bride eventually reveals his secret, and the monster is punished—hacked to bits or burned alive. Though the story often has fantastic aspects—a talking bird, people who miraculously come back to life when their dismembered parts are reunited, a magical key or egg that proves that the wife found the chamber—true anxiety lies at its heart. Marriage is a gamble, it reminds us, and any husband could turn out to be a wife-killer.

FILMMAKER ANNA BILLER begins her debut novel, Bluebeard’s Castle, with a warning: “Some husbands,” she writes, “are pussycats, some are dullards or harmless rogues, and some are Bluebeards.” Folklore and literary history are full of Bluebeards: Charles Perrault’s original fairy tale, two Brothers Grimm versions, Jane Eyre’s Mr. Rochester, modern retellings by writers, composers, and directors ranging from Georges Méliès and Béla Bartók to Helen Oyeyemi and Catherine Breillat. The elements of the story remain essentially the same: a young woman marries a mysterious, wealthy widower. Despite warnings (sometimes from her husband, sometimes from outsiders), she explores the recesses of his house and discovers that he has murdered all his former wives and keeps their bodies in a hidden chamber. The intrepid bride eventually reveals his secret, and the monster is punished—hacked to bits or burned alive. Though the story often has fantastic aspects—a talking bird, people who miraculously come back to life when their dismembered parts are reunited, a magical key or egg that proves that the wife found the chamber—true anxiety lies at its heart. Marriage is a gamble, it reminds us, and any husband could turn out to be a wife-killer. For a son of the titular city, reading Federico García Lorca’s Poet in New York is akin to curling into your lover, your nose dipped in the well of their collarbone, as they detail your mother’s various personality disorders. Yes, Federico, yes, my mother is thoroughly racist and takes every opportunity to remind me, her sometimes destitute child, about the silent cruelty of money. “At least you got to leave,” I want to tell him. “Imagine being stuck with her for the rest of your life.” He would likely understand my irrational attachment; after all, he was so consumed by Spain, its art and its politics, that his country would go on to swallow him whole.

For a son of the titular city, reading Federico García Lorca’s Poet in New York is akin to curling into your lover, your nose dipped in the well of their collarbone, as they detail your mother’s various personality disorders. Yes, Federico, yes, my mother is thoroughly racist and takes every opportunity to remind me, her sometimes destitute child, about the silent cruelty of money. “At least you got to leave,” I want to tell him. “Imagine being stuck with her for the rest of your life.” He would likely understand my irrational attachment; after all, he was so consumed by Spain, its art and its politics, that his country would go on to swallow him whole. People of different nationalities appear to vary in their use of hand gestures, according to a study that seems to reinforce the idea that Italians, in particular, “talk with their hands”.

People of different nationalities appear to vary in their use of hand gestures, according to a study that seems to reinforce the idea that Italians, in particular, “talk with their hands”.

It is a familiar story: a small group of animals living in a wooded grassland begin, against all odds, to populate Earth. At first, they occupy a specific ecological place in the landscape, kept in check by other species. Then something changes. The animals find a way to travel to new places. They learn to cope with unpredictability. They adapt to new kinds of food and shelter. They are clever. And they are aggressive.

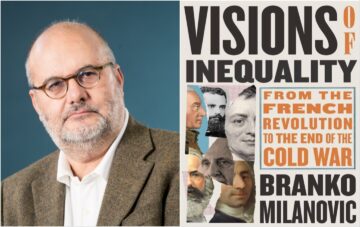

It is a familiar story: a small group of animals living in a wooded grassland begin, against all odds, to populate Earth. At first, they occupy a specific ecological place in the landscape, kept in check by other species. Then something changes. The animals find a way to travel to new places. They learn to cope with unpredictability. They adapt to new kinds of food and shelter. They are clever. And they are aggressive. Branko Milanović’s Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War is an intellectual history of how leading economists since the 18th century, from Adam Smith to Karl Marx and beyond, have thought about income distribution and inequality.

Branko Milanović’s Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War is an intellectual history of how leading economists since the 18th century, from Adam Smith to Karl Marx and beyond, have thought about income distribution and inequality. N

N Brown bears once roamed widely across Western Europe. But already by the Middle Ages, hunting and habitat degradation had pushed their populations to the east and north. In the Alpine region of Italy, at times with the backing of the state,

Brown bears once roamed widely across Western Europe. But already by the Middle Ages, hunting and habitat degradation had pushed their populations to the east and north. In the Alpine region of Italy, at times with the backing of the state,  In “

In “