Sameer Pandya at the LARB:

THIS YEAR marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India. I’ve never loved the novel, nor have I been able to let go of it. And so I started reading it again as I began a passage of my own to India—where I lived until I was eight—with my wife and our two teenage sons.

THIS YEAR marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India. I’ve never loved the novel, nor have I been able to let go of it. And so I started reading it again as I began a passage of my own to India—where I lived until I was eight—with my wife and our two teenage sons.

Across his work, but particularly in Passage, Forster uses miscommunication, or what he calls “muddles,” as a productive source of narrative tension and propulsion. “Except for the Marabar Caves—and they are twenty miles off—the city of Chandrapore presents nothing extraordinary.” The opening line sets up the location of the novel’s primary action in a cave that produces only an echo—the absence of real communication.

A young Englishwoman named Adela Quested arrives in British India with Mrs. Moore, her prospective mother-in-law, so that Adela can determine if she and Mrs. Moore’s son, Ronny, are the right match.

more here.

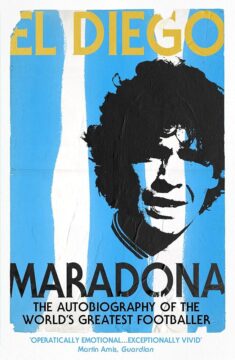

While reading Maradona’s autobiography this past winter, I found that every few pages I would whisper or write in the margins, “I love you, Maradona.” Sadness crept up on me as I turned to the last chapter, and it intensified to heartbreak when I read its first lines: “They say I can’t keep quiet, that I talk about everything, and it’s true. They say I fell out with the Pope. It’s true.” I was devastated to be leaving Maradona’s world and returning to the ordinary one, where nobody ever picks a fight with the Pope.

While reading Maradona’s autobiography this past winter, I found that every few pages I would whisper or write in the margins, “I love you, Maradona.” Sadness crept up on me as I turned to the last chapter, and it intensified to heartbreak when I read its first lines: “They say I can’t keep quiet, that I talk about everything, and it’s true. They say I fell out with the Pope. It’s true.” I was devastated to be leaving Maradona’s world and returning to the ordinary one, where nobody ever picks a fight with the Pope. Almost 25 million adults in the U.S. have

Almost 25 million adults in the U.S. have  This six-legged animal isn’t an insect: it’s a mouse with two extra limbs where its genitals should be. Research on this genetically engineered rodent, which was published on 20 March in Nature Communications

This six-legged animal isn’t an insect: it’s a mouse with two extra limbs where its genitals should be. Research on this genetically engineered rodent, which was published on 20 March in Nature Communications Despite the stereotype of being the Norman Rockwell of verse, Robert Frost’s standing, even sixty-one years after his death, remains blue-chip, still perhaps the most famous American poet among the general public. Frost’s work remains anthologized and interpreted, and taught in secondary and undergraduate classrooms; his lyrics among the handful that can be expected to be namedropped as a reader’s favorite poem (two roads and all of that). If anything, Frost has suffered from the albatross of presumed accessibility. Among the luminaries of American Modernism, Ezra Pound was experimental, T.S. Eliot cerebral, H.D. hermetic, Langston Hughes revolutionary, Wallace Stevens incandescent, and William Carlos Williams visionary, but Frost is readable. David Orr writes in his excellent book-length close reading The Road Not Taken: Finding America in the Poem Everyone Loves and Almost Everyone Gets Wrong (2015) that Frost is a poet whose “signature phrases have become so ubiquitous, so much a part of everything from coffee mugs to refrigerator magnets to graduation speeches” that it can become easy to forget the man who penned such phrases.

Despite the stereotype of being the Norman Rockwell of verse, Robert Frost’s standing, even sixty-one years after his death, remains blue-chip, still perhaps the most famous American poet among the general public. Frost’s work remains anthologized and interpreted, and taught in secondary and undergraduate classrooms; his lyrics among the handful that can be expected to be namedropped as a reader’s favorite poem (two roads and all of that). If anything, Frost has suffered from the albatross of presumed accessibility. Among the luminaries of American Modernism, Ezra Pound was experimental, T.S. Eliot cerebral, H.D. hermetic, Langston Hughes revolutionary, Wallace Stevens incandescent, and William Carlos Williams visionary, but Frost is readable. David Orr writes in his excellent book-length close reading The Road Not Taken: Finding America in the Poem Everyone Loves and Almost Everyone Gets Wrong (2015) that Frost is a poet whose “signature phrases have become so ubiquitous, so much a part of everything from coffee mugs to refrigerator magnets to graduation speeches” that it can become easy to forget the man who penned such phrases. Technology is changing the world, in good and bad ways. Artificial intelligence, internet connectivity, biological engineering, and climate change are dramatically altering the parameters of human life. What can we say about how this will extend into the future? Will the pace of change level off, or smoothly continue, or hit a singularity in a finite time? In this informal solo episode, I think through what I believe will be some of the major forces shaping how human life will change over the decades to come, exploring the very real possibility that we will experience a dramatic phase transition into a new kind of equilibrium.

Technology is changing the world, in good and bad ways. Artificial intelligence, internet connectivity, biological engineering, and climate change are dramatically altering the parameters of human life. What can we say about how this will extend into the future? Will the pace of change level off, or smoothly continue, or hit a singularity in a finite time? In this informal solo episode, I think through what I believe will be some of the major forces shaping how human life will change over the decades to come, exploring the very real possibility that we will experience a dramatic phase transition into a new kind of equilibrium. On my last visit to the National Gallery in London in October 2022, during Frieze Week, the wall beneath Vincent Van Gogh’s iconic Sunflowers still displayed noticeable palm-sized daubs of unmatched gray paint. The day before, Just Stop Oil protestors Phoebe Plummer, and Anna Holland

On my last visit to the National Gallery in London in October 2022, during Frieze Week, the wall beneath Vincent Van Gogh’s iconic Sunflowers still displayed noticeable palm-sized daubs of unmatched gray paint. The day before, Just Stop Oil protestors Phoebe Plummer, and Anna Holland  When it comes to our understanding of the world, we are all like the blind men in the story of the blind men and the elephant. We each know the elephant from our own small vantage point, and what we know is partial and prone to distortions. It is from speaking to one another, reading one another, that a more accurate picture appears. Unfortunately, too often, those we speak to and read come from places very close to ours, whether physically or ideologically, and so the elephant we see together looks to us uncannily like something else, like a wall or a weapon or a trophy, perhaps. I would like to describe the elephant, the world, as I perceive it from my vantage point in Lahore, Pakistan, in the early months of the year 2024. I do this in the hope that each of us, in describing it, helps all of us see it a little better.

When it comes to our understanding of the world, we are all like the blind men in the story of the blind men and the elephant. We each know the elephant from our own small vantage point, and what we know is partial and prone to distortions. It is from speaking to one another, reading one another, that a more accurate picture appears. Unfortunately, too often, those we speak to and read come from places very close to ours, whether physically or ideologically, and so the elephant we see together looks to us uncannily like something else, like a wall or a weapon or a trophy, perhaps. I would like to describe the elephant, the world, as I perceive it from my vantage point in Lahore, Pakistan, in the early months of the year 2024. I do this in the hope that each of us, in describing it, helps all of us see it a little better. Scientists at a recently opened cancer institute at

Scientists at a recently opened cancer institute at  Great tracts of culture, notably the

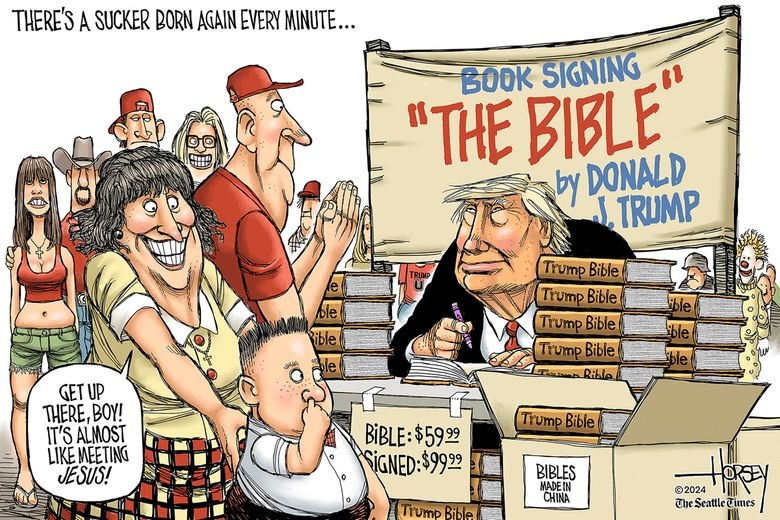

Great tracts of culture, notably the  P.T. Barnum, the great 19th century showman, circus owner and hoax promoter, is quoted as saying, “There’s a sucker born every minute.” Donald J. Trump, the great 21st century con man, political phenomenon and hoax promoter, would heartily agree. Trump has built a weirdly successful career in business, entertainment and politics based on his uncanny ability to convince legions of suckers to buy into his self-aggrandizing schemes, from Trump University, the Trump charity and the Big Lie, to his latest scam tricking thousands of poor chumps into chipping in to pay his millions of dollars in legal bills.

P.T. Barnum, the great 19th century showman, circus owner and hoax promoter, is quoted as saying, “There’s a sucker born every minute.” Donald J. Trump, the great 21st century con man, political phenomenon and hoax promoter, would heartily agree. Trump has built a weirdly successful career in business, entertainment and politics based on his uncanny ability to convince legions of suckers to buy into his self-aggrandizing schemes, from Trump University, the Trump charity and the Big Lie, to his latest scam tricking thousands of poor chumps into chipping in to pay his millions of dollars in legal bills.