Editor’s Note: I never met Frans in person but we exchanged scores of emails and he even wrote for 3QD for a while. He was, in addition to being one of the most distinguished scientists of our time, a brilliant writer and explicator of difficult science. He will be very much missed by many, including me. I had no idea he was ill and was shocked to hear of his death at the young age of 75. His writings for 3QD can be seen here.

From Phys.org:

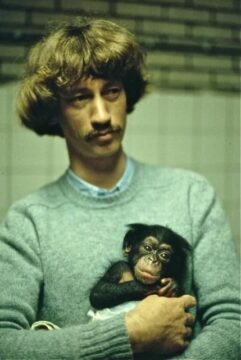

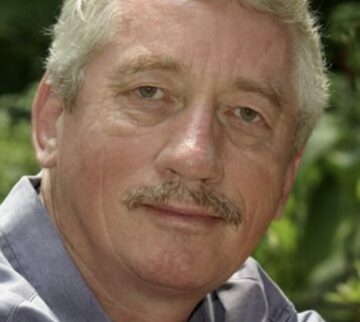

The Netherlands-born scientist spent decades studying chimpanzees and apes, and his biological research eventually helped debunk the theory that primates including humans were naturally “nasty” and aggressive competitors.

The Netherlands-born scientist spent decades studying chimpanzees and apes, and his biological research eventually helped debunk the theory that primates including humans were naturally “nasty” and aggressive competitors.

“De Waal shattered long-held ideas about what it means to be an animal and a human,” Emory, based in Atlanta in the US state of Georgia, said in its statement.

“He demonstrated the roots of human nature in our closest living relatives through his studies of conflict resolution, reconciliation, cooperation, empathy, fairness, morality, social learning and culture in chimpanzees, bonobos and capuchin monkeys.”

Lynne Nygaard, chair of Emory’s Department of Psychology, remembered de Waal as “an extraordinarily deep thinker” who could offer “insights that cut across disciplines.”

More here.

I’ve spent the last five years digging deep into the history of American crime forensics, writing a widely read 2020 New York Times story about the origins of the rape kit and interviewing people for a forthcoming book. I’ve learned that the rape kit is the unsung hero of forensics — when used correctly, it can identify violent criminals and also prevent wrongly accused men from going to prison. But unfortunately, it has never really been given a chance to work. It could be so much better.

I’ve spent the last five years digging deep into the history of American crime forensics, writing a widely read 2020 New York Times story about the origins of the rape kit and interviewing people for a forthcoming book. I’ve learned that the rape kit is the unsung hero of forensics — when used correctly, it can identify violent criminals and also prevent wrongly accused men from going to prison. But unfortunately, it has never really been given a chance to work. It could be so much better.

Does free-market capitalism buttress democracy, or does it unleash anti-democratic forces? This question first emerged in the Age of Enlightenment, when capitalism was viewed optimistically and welcomed as a vehicle of liberation from the rigid feudal order. Many envisioned an equal-opportunity society of small producers and consumers, where no one would have undue market power, and where prices would be determined by the “invisible hand.” Under such conditions, democracy and capitalism are two sides of the same coin.

Does free-market capitalism buttress democracy, or does it unleash anti-democratic forces? This question first emerged in the Age of Enlightenment, when capitalism was viewed optimistically and welcomed as a vehicle of liberation from the rigid feudal order. Many envisioned an equal-opportunity society of small producers and consumers, where no one would have undue market power, and where prices would be determined by the “invisible hand.” Under such conditions, democracy and capitalism are two sides of the same coin. Emory University primatologist Frans de Waal — who pioneered studies of animal cognition while also writing best-selling books that helped popularize the field around the globe — passed away March 14, 2024, from stomach cancer.

Emory University primatologist Frans de Waal — who pioneered studies of animal cognition while also writing best-selling books that helped popularize the field around the globe — passed away March 14, 2024, from stomach cancer. The famed coastal dunes that

The famed coastal dunes that  Since the 1950s, scientists have had a pretty good idea of how muscles work. The protein at the centre of the action is myosin, a molecular motor that ratchets itself along rope-like strands of actin proteins — grasping, pulling, releasing and grasping again — to make muscle cells contract.

Since the 1950s, scientists have had a pretty good idea of how muscles work. The protein at the centre of the action is myosin, a molecular motor that ratchets itself along rope-like strands of actin proteins — grasping, pulling, releasing and grasping again — to make muscle cells contract. Weschler: It’s interesting in this context, you mentioned a second ago Giovanni’s Room, where part of the story is clearly about a deeply closeted white figure, an American in Paris, who gets involved with somebody who is clearly much more at ease with his sexuality. The relationship just curdles and he destroys both himself and his lover through his inability to be free. And he’s not only talking about gayness in that situation.

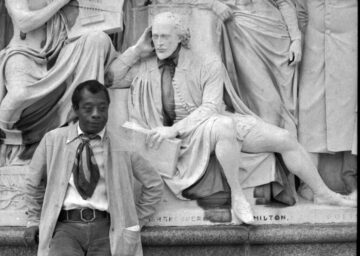

Weschler: It’s interesting in this context, you mentioned a second ago Giovanni’s Room, where part of the story is clearly about a deeply closeted white figure, an American in Paris, who gets involved with somebody who is clearly much more at ease with his sexuality. The relationship just curdles and he destroys both himself and his lover through his inability to be free. And he’s not only talking about gayness in that situation. It is one of the great love stories of history and therefore inherently interesting because who isn’t interested in a great love story? Actually, it is a terrible love story as well. That is also what makes it interesting. The love part of the love story only lasted about a year in the early twelfth century. That’s when the great philosopher Peter Abelard was in Paris teaching and making fools of the other great minds to be found in Paris at the time, at least as he tells it, but other sources seem to confirm that Abelard was indeed just sharper and more witty and quicker on his feet than anyone else, plus he was a damn good poet and wrote wonderful popular songs and was handsome as hell.

It is one of the great love stories of history and therefore inherently interesting because who isn’t interested in a great love story? Actually, it is a terrible love story as well. That is also what makes it interesting. The love part of the love story only lasted about a year in the early twelfth century. That’s when the great philosopher Peter Abelard was in Paris teaching and making fools of the other great minds to be found in Paris at the time, at least as he tells it, but other sources seem to confirm that Abelard was indeed just sharper and more witty and quicker on his feet than anyone else, plus he was a damn good poet and wrote wonderful popular songs and was handsome as hell. I interviewed de Waal in 2007 while researching my book

I interviewed de Waal in 2007 while researching my book  The Netherlands-born scientist spent decades studying chimpanzees and

The Netherlands-born scientist spent decades studying chimpanzees and  W

W As a Ph.D. student, I spent many days and nights standing on a steep forested slope in the rain, measuring how water drops move into the soil. I loved the outdoors, and it was more like play than work. Many nights, I would dream about my research. I was endlessly curious about what I saw in the field and thrilled when I could connect it to what I read. My ideas seemed to flow like the stream I was trying to understand. But when I became a professor, I was inundated with responsibilities and my creative stream slowed to a trickle. It took me decades to figure out how to revive it.

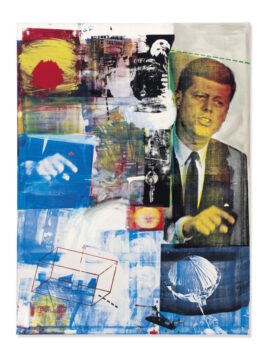

As a Ph.D. student, I spent many days and nights standing on a steep forested slope in the rain, measuring how water drops move into the soil. I loved the outdoors, and it was more like play than work. Many nights, I would dream about my research. I was endlessly curious about what I saw in the field and thrilled when I could connect it to what I read. My ideas seemed to flow like the stream I was trying to understand. But when I became a professor, I was inundated with responsibilities and my creative stream slowed to a trickle. It took me decades to figure out how to revive it. A new documentary delves into the scandals that plagued the 1964 Venice Biennale, where Robert Rauschenberg became the first American to earn the Golden Lion grand prize amid allegations of a rigged jury. Critic and director Amei Wallach’s film

A new documentary delves into the scandals that plagued the 1964 Venice Biennale, where Robert Rauschenberg became the first American to earn the Golden Lion grand prize amid allegations of a rigged jury. Critic and director Amei Wallach’s film  “There isn’t really anybody who occupies the lens to the extent that Lindsay Lohan does,” the artist Richard Phillips observed in 2012. “Something happens when she steps in front of the camera … She is very aware of the way that an icon is constructed, and that’s something that is unique.” Phillips, who has long used famous people as his muses, was promoting a new short film he had made with the then-twenty-five-year-old actress. Standing in a fulgid ocean in a silvery-white bathing suit, her eyeliner and false lashes dark as a depressive mood, she is meant to look healthily Californian, but her beauty is a little rumpled, and even in close-up she cannot quite meet the camera’s gaze. The impression left by Lindsay Lohan (2011), Phillips’s film, is that of an artist’s model who is incapable of behaving like one, having been cursed with the roiling interior life of a consummate actress. Most traditional print models can successfully empty out their eyes for fashion films and photoshoots, easily signifying nothing, but Lohan looks fearful, guarded, as if somewhere just beyond the camera she can see the terrible future. Unlike her heroine Marilyn Monroe, Phillips also observed in a promotional interview, Lohan is “still alive, and she’s more powerful than ever.”

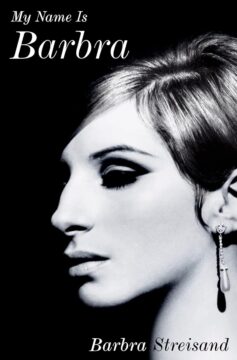

“There isn’t really anybody who occupies the lens to the extent that Lindsay Lohan does,” the artist Richard Phillips observed in 2012. “Something happens when she steps in front of the camera … She is very aware of the way that an icon is constructed, and that’s something that is unique.” Phillips, who has long used famous people as his muses, was promoting a new short film he had made with the then-twenty-five-year-old actress. Standing in a fulgid ocean in a silvery-white bathing suit, her eyeliner and false lashes dark as a depressive mood, she is meant to look healthily Californian, but her beauty is a little rumpled, and even in close-up she cannot quite meet the camera’s gaze. The impression left by Lindsay Lohan (2011), Phillips’s film, is that of an artist’s model who is incapable of behaving like one, having been cursed with the roiling interior life of a consummate actress. Most traditional print models can successfully empty out their eyes for fashion films and photoshoots, easily signifying nothing, but Lohan looks fearful, guarded, as if somewhere just beyond the camera she can see the terrible future. Unlike her heroine Marilyn Monroe, Phillips also observed in a promotional interview, Lohan is “still alive, and she’s more powerful than ever.” When I read that Barbra Streisand’s memoir, My Name Is Barbra (2023), would be 970 pages long, a devilish chuckle bubbled up from deep within me. There was something ecstatic about this moment—How pharaonic the ambition! What an absolute thrill that a woman famous for show business—and not, say, the Nobel Peace Prize—believes her life story worthy of such an expansive word count. I am grateful that someone, somewhere, isn’t endlessly struggling to feign correct attitudes, that someone believes there is time and space to read 970 pages about the life and times of Barbra Streisand, one of those someones being Barbra Streisand.

When I read that Barbra Streisand’s memoir, My Name Is Barbra (2023), would be 970 pages long, a devilish chuckle bubbled up from deep within me. There was something ecstatic about this moment—How pharaonic the ambition! What an absolute thrill that a woman famous for show business—and not, say, the Nobel Peace Prize—believes her life story worthy of such an expansive word count. I am grateful that someone, somewhere, isn’t endlessly struggling to feign correct attitudes, that someone believes there is time and space to read 970 pages about the life and times of Barbra Streisand, one of those someones being Barbra Streisand.