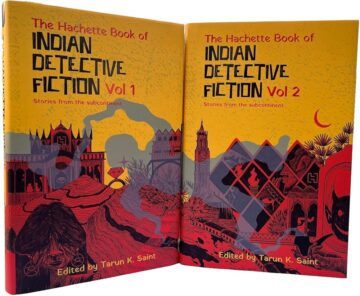

Soni Wadhwa in the Asian Review of Books:

Detective fiction in the West is often grouped with crime fiction and thrillers; but in detective fiction, the focus is on a puzzle and the process of solving it. It’s a game with the reader in which a mystery needs to be unraveled before the detective figures it out. In some places, the detective becomes a figure of interest in himself—detective figures have been, traditionally if less so at present, more often than not, men—a complex personality whose story is interesting and deserves an independent treatment of its own. It is a genre that solves problems, finds answers, holds the culprit accountable: all very attractive attributes for those who just like a good story.

Detective fiction in the West is often grouped with crime fiction and thrillers; but in detective fiction, the focus is on a puzzle and the process of solving it. It’s a game with the reader in which a mystery needs to be unraveled before the detective figures it out. In some places, the detective becomes a figure of interest in himself—detective figures have been, traditionally if less so at present, more often than not, men—a complex personality whose story is interesting and deserves an independent treatment of its own. It is a genre that solves problems, finds answers, holds the culprit accountable: all very attractive attributes for those who just like a good story.

To this genre, Indian writers bring a depth of cultural context, making the genre more about societal constructs of crime, power, and inequalities of caste, gender, and so on than about a straightforward resolution of a problem. In order to archive the diversity of this form in India, literary critic and translator Tarun K Saint has produced a two volume anthology titled The Hachette Book of Indian Detective Fiction which brings together writing both in English and in translation (from Tamil and Bengali).

More here.

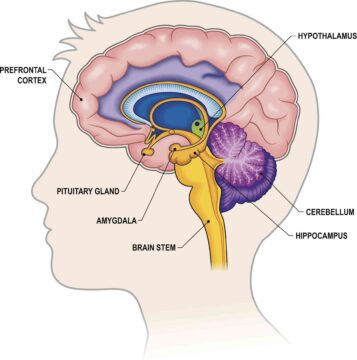

The latest wave of AI relies heavily on machine learning, in which software identifies patterns in data on its own, without being given any predetermined rules as to how to organize or classify the information. These patterns can be inscrutable to humans. The most advanced machine-learning systems use neural networks: software inspired by the architecture of the brain. They simulate layers of neurons, which transform information as it passes from layer to layer. As in human brains, these networks strengthen and weaken neural connections as they learn, but it’s hard to see why certain connections are affected. As a result, researchers often talk about AI as ‘

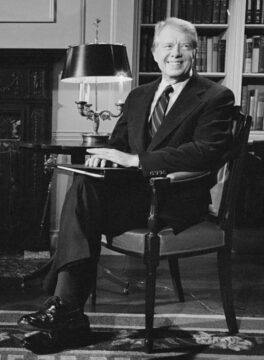

The latest wave of AI relies heavily on machine learning, in which software identifies patterns in data on its own, without being given any predetermined rules as to how to organize or classify the information. These patterns can be inscrutable to humans. The most advanced machine-learning systems use neural networks: software inspired by the architecture of the brain. They simulate layers of neurons, which transform information as it passes from layer to layer. As in human brains, these networks strengthen and weaken neural connections as they learn, but it’s hard to see why certain connections are affected. As a result, researchers often talk about AI as ‘ On September 17, 1978, U.S. President Jimmy Carter faced a momentous crisis. For nearly two weeks, he had been holed up at Camp David with Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, trying to hammer out a historic peace deal. Although the hard-liner Begin had proven intransigent on many issues, Carter had made enormous progress by going around him and negotiating directly with Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan, Defense Minister Ezer Weizman, and Legal Adviser Aharon Barak. On the 13th day, however, Begin drew the line. He announced he could compromise no further and was leaving. The talks on which Carter had staked his presidency would all be for naught.

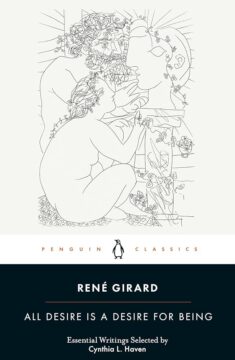

On September 17, 1978, U.S. President Jimmy Carter faced a momentous crisis. For nearly two weeks, he had been holed up at Camp David with Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, trying to hammer out a historic peace deal. Although the hard-liner Begin had proven intransigent on many issues, Carter had made enormous progress by going around him and negotiating directly with Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan, Defense Minister Ezer Weizman, and Legal Adviser Aharon Barak. On the 13th day, however, Begin drew the line. He announced he could compromise no further and was leaving. The talks on which Carter had staked his presidency would all be for naught. Girard’s corpus is not just an erudite self-help manual, however; his intellectual landscape is not intended to be therapeutic, and yet it is. What he came to see was not a comfort, however, but something fierce and intractable. What he learned about the individual also limns the destiny of our species. Our impossible plight: the mechanism of scapegoat violence—whether on the level of the individual, or society, or epoch—is rooted in the very imitation that teaches us to love and learn, in fact, the very tissue that connects us with the rest of humanity.

Girard’s corpus is not just an erudite self-help manual, however; his intellectual landscape is not intended to be therapeutic, and yet it is. What he came to see was not a comfort, however, but something fierce and intractable. What he learned about the individual also limns the destiny of our species. Our impossible plight: the mechanism of scapegoat violence—whether on the level of the individual, or society, or epoch—is rooted in the very imitation that teaches us to love and learn, in fact, the very tissue that connects us with the rest of humanity. Have you ever said “I hate you” to someone? What about using the “h-word” in casual conversation, like “I hate broccoli”? What are you really feeling when you say that you hate something or someone?

Have you ever said “I hate you” to someone? What about using the “h-word” in casual conversation, like “I hate broccoli”? What are you really feeling when you say that you hate something or someone? If you’ve ever vented to ChatGPT about troubles in life, the responses can sound empathetic. The chatbot delivers affirming support, and—when prompted—even gives advice like a best friend. Unlike older chatbots, the seemingly “empathic” nature of the latest AI models has already galvanized the psychotherapy community, with

If you’ve ever vented to ChatGPT about troubles in life, the responses can sound empathetic. The chatbot delivers affirming support, and—when prompted—even gives advice like a best friend. Unlike older chatbots, the seemingly “empathic” nature of the latest AI models has already galvanized the psychotherapy community, with  My own tutee students, whom I met on a regular basis, were reporting poor mental health or asking for extensions because they were unable to meet deadlines that were stressing them out. They were overly obsessed with marks and other performance outcomes, and this impacted not only on them, but also on the teaching and support staff who were increasingly dealing with alleviating student anxiety. Students wanted more support that most felt was lacking and, in an effort to deal with the issue, the university had invested heavily, making more provision for mental health services. The problem with this strategy, however, is that by the time someone seeks out professional services, they are already at a crisis point. I felt compelled to do something.

My own tutee students, whom I met on a regular basis, were reporting poor mental health or asking for extensions because they were unable to meet deadlines that were stressing them out. They were overly obsessed with marks and other performance outcomes, and this impacted not only on them, but also on the teaching and support staff who were increasingly dealing with alleviating student anxiety. Students wanted more support that most felt was lacking and, in an effort to deal with the issue, the university had invested heavily, making more provision for mental health services. The problem with this strategy, however, is that by the time someone seeks out professional services, they are already at a crisis point. I felt compelled to do something. For months, OpenAI has been losing employees who care deeply about making sure

For months, OpenAI has been losing employees who care deeply about making sure  Today, Amit Shah isn’t home minister for Gujarat, but all of India. From the heart of power in Delhi, he is in charge of domestic policy, commands the capital city’s police force, and oversees the Indian state’s intelligence apparatus. He is, simply put, the second-most powerful man in the country. With the BJP poised to win the current general election, he is all but certain to remain so for at least the next five years. For Modi, he is what Dick Cheney and Karl Rove were for George W Bush – the muscle as well as the brain – rolled into one. Over the past decade, he has been the key architect in remaking India according to the BJP’s Hindu nationalist ideology.

Today, Amit Shah isn’t home minister for Gujarat, but all of India. From the heart of power in Delhi, he is in charge of domestic policy, commands the capital city’s police force, and oversees the Indian state’s intelligence apparatus. He is, simply put, the second-most powerful man in the country. With the BJP poised to win the current general election, he is all but certain to remain so for at least the next five years. For Modi, he is what Dick Cheney and Karl Rove were for George W Bush – the muscle as well as the brain – rolled into one. Over the past decade, he has been the key architect in remaking India according to the BJP’s Hindu nationalist ideology. S

S William Ewart Gladstone was Britain’s prime minister four times between 1868 and 1894, a member of Parliament for more than sixty years, a brilliant and passionate orator, an accomplished writer, and an indefatigable social reformer. Lord Kilbracken, his private secretary, estimated that if a figure of 100 could represent the energy of an ordinary man and 200 that of an exceptional one, Gladstone’s energy would be represented by a figure of at least 1,000.

William Ewart Gladstone was Britain’s prime minister four times between 1868 and 1894, a member of Parliament for more than sixty years, a brilliant and passionate orator, an accomplished writer, and an indefatigable social reformer. Lord Kilbracken, his private secretary, estimated that if a figure of 100 could represent the energy of an ordinary man and 200 that of an exceptional one, Gladstone’s energy would be represented by a figure of at least 1,000. The day when

The day when

‘C

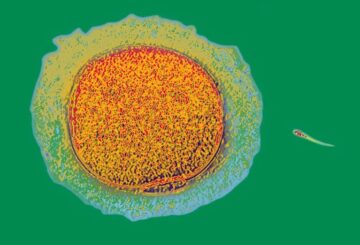

‘C I am a neurobiologist focused on understanding the chemicals and brain regions that

I am a neurobiologist focused on understanding the chemicals and brain regions that