Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Jonathan Lethem On His Stories

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rethinking nuclear

Edward A. Friedman at the Oxford University Press blog:

As someone who has spent decades studying the evolution of nuclear energy, I’ve seen its emergence as a promising transformative technology, its stagnation as a consequence of dramatic accidents and its current re-emergence as a potential solution to the challenges of global warming.

As someone who has spent decades studying the evolution of nuclear energy, I’ve seen its emergence as a promising transformative technology, its stagnation as a consequence of dramatic accidents and its current re-emergence as a potential solution to the challenges of global warming.

While the issues of global warming and sustainable energy strategies are among the most consequential in today’s society, it is difficult to find objective sources that elucidate these topics. Discourse on this subject is often positioned at one or another polemical extreme. Further complicating the flow of objective information is the involvement of advocates of vested interests as seen in the lobbying efforts of the coal, gas and oil industries. My goal has been to present nuclear energy’s potential role in a sustainable energy future—alongside renewables like wind and solar—without ideological baggage.

An additional hurdle that must be overcome in dealing with the pros and cons of nuclear energy is the psychological context in which fear of nuclear weapons and of radiation impedes rational analysis.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why Immanuel Kant Still Has More to Teach Us

Adam Kirsch at The New Yorker:

The central insight that these disparate thinkers took from Kant is that the world isn’t simply a thing, or a collection of things, given to us to perceive. Rather, our minds help create the reality we experience. In particular, Kant argued that time, space, and causality, which we ordinarily take for granted as the most basic aspects of the world, are better understood as forms imposed on the world by the human mind.

The central insight that these disparate thinkers took from Kant is that the world isn’t simply a thing, or a collection of things, given to us to perceive. Rather, our minds help create the reality we experience. In particular, Kant argued that time, space, and causality, which we ordinarily take for granted as the most basic aspects of the world, are better understood as forms imposed on the world by the human mind.

The parallel with Copernicus turns out to be apt. Before Copernicus and Kepler and Galileo, people assumed that the sun and the planets revolved around the Earth, and justifiably so—that’s how it appears to us when we look up at the sky. It took a lot of close observation and ingenious reasoning for astronomers to understand that this was a trick of perspective, and that in fact it is the Earth that revolves around the sun. Similarly, it is natural for human beings to assume that the way the world appears to us—extended in three dimensions, constantly moving from the past into the future, changing as its different elements interact—is the way it really is. But, Kant maintained, this is also a trick of perspective. Space and time do not exist objectively, only subjectively, as forms of our experience. He wrote that it is “from the human point of view only that we can speak of space, extended objects, etc.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Best New TV Shows of October 2025

Judy Berman in Time Magazine:

Horror is ubiquitous on TV at this time of year, and those of us who love a good scare—myself very much included—usually look forward to it. Unfortunately, October 2025’s selection of IP expansions (IT: Welcome to Derry, Anne Rice’s Talamasca) and true crime murdersploitation left me mostly cold. You will find one worthwhile serial-killer story among this month’s highlights, though—plus a thriller with the deceptively spooky title Down Cemetery Road, a docudrama that resurrects Margaret Thatcher, an in-depth profile of a filmmaker who stares into the darkness of the human soul, and a dispatch from the delightfully unhinged brain of Tim Robinson.

Horror is ubiquitous on TV at this time of year, and those of us who love a good scare—myself very much included—usually look forward to it. Unfortunately, October 2025’s selection of IP expansions (IT: Welcome to Derry, Anne Rice’s Talamasca) and true crime murdersploitation left me mostly cold. You will find one worthwhile serial-killer story among this month’s highlights, though—plus a thriller with the deceptively spooky title Down Cemetery Road, a docudrama that resurrects Margaret Thatcher, an in-depth profile of a filmmaker who stares into the darkness of the human soul, and a dispatch from the delightfully unhinged brain of Tim Robinson.

Mr. Scorsese (Apple TV)

It’s always fascinating to see one great artist consider another. Over the course of a career spanning more than half a century, Martin Scorsese has directed essential documentaries on so many luminaries: Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, the Band, Elia Kazan, Fran Lebowitz, and the list goes on. Now, Rebecca Miller—the filmmaker, novelist, daughter of Arthur Miller, and wife of two-time Scorsese leading man Daniel Day-Lewis—has turned her lens on Marty, in an excellent five-part docuseries rightly framed as a “portrait.” It’s immediately clear that Miller was the ideal director for this project, wise about both the psychological toll of uncompromising artistry and the pain artists so often inflict on the people who love them.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Classic Jonathan Lethem

Justin St. Clair at the LARB:

IN THESE PROFOUNDLY unsettling times, literary criticism can seem a little frivolous. We’re no longer slouching toward some imagined autocratic future; we’re midway through the dissolution of the American experiment. We’ve got concentration camps and mass deportations, the senseless dismantlement of essential federal agencies, military personnel on foot patrol in our nation’s capital. There’s a relentless assault on public media, public education, public service, public health, and anything else that an earlier generation would have reasonably considered to be in the public’s interest. It’s dystopian and thoroughly demoralizing. And the most we can manage, it would seem, is to twiddle our thumbs like so many complicit functionaries, doomscrolling against the inevitable.

IN THESE PROFOUNDLY unsettling times, literary criticism can seem a little frivolous. We’re no longer slouching toward some imagined autocratic future; we’re midway through the dissolution of the American experiment. We’ve got concentration camps and mass deportations, the senseless dismantlement of essential federal agencies, military personnel on foot patrol in our nation’s capital. There’s a relentless assault on public media, public education, public service, public health, and anything else that an earlier generation would have reasonably considered to be in the public’s interest. It’s dystopian and thoroughly demoralizing. And the most we can manage, it would seem, is to twiddle our thumbs like so many complicit functionaries, doomscrolling against the inevitable.

In this context, I don’t exactly know what to do with Jonathan Lethem’s latest. And I’m not entirely sure he did either. An anthology decades in the making, A Different Kind of Tension presents, in chronological order, 30 of Lethem’s best short stories, from “Walking the Moons” (1990) to “The Red Sun School of Thoughts” (2024). All, with the exception of the final piece, are available elsewhere, but the paucity of new material in no way diminishes the collection.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How Does Daylight Saving Time Affect Circadian Rhythm?

Shelby Bradford in The Scientist:

As countries around the world begin to turn their clocks back an hour, some people may rejoice at the extra time in bed while others might mourn the loss of evening light. For many sleep and circadian rhythm biologists, the end of daylight saving time is an overall positive thing. In fact, many groups, including the Society for Research on Biological Rhythms, have petitioned governments to adopt permanent standard time to improve public health. “Basically, that’s because the body’s clock and social clock will match most closely under a standard time,” said Kevin Koronowksi, a chronobiologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and member of the Society for Research and Biological Rhythms. Koronowski studies the relationship between circadian rhythm and metabolism.

As countries around the world begin to turn their clocks back an hour, some people may rejoice at the extra time in bed while others might mourn the loss of evening light. For many sleep and circadian rhythm biologists, the end of daylight saving time is an overall positive thing. In fact, many groups, including the Society for Research on Biological Rhythms, have petitioned governments to adopt permanent standard time to improve public health. “Basically, that’s because the body’s clock and social clock will match most closely under a standard time,” said Kevin Koronowksi, a chronobiologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and member of the Society for Research and Biological Rhythms. Koronowski studies the relationship between circadian rhythm and metabolism.

In humans, the circadian rhythm describes the organization of physiological processes that occur on a roughly 24 hour cycle, creating a biological clock. Although the body internally regulates the genes related to coordinating cells’ clocks, circadian rhythm synchronizes to the light-dark cycles of people’s external environment.1,2 For example, melatonin production increases as the day draws to a close, while cortisol levels rise in the morning.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Lockdown Drill

……..

at their desks, they fill each row, my little ducks.

—–

by Nicole Caruso Garcia

from Rattle Magazine

““A designer launched a line of school shooting sweatshirts, complete with bullet holes. Like many people, I was repulsed. Also this week, Sandy Hook Promise launched a timely PSA called ‘Back to School Essentials.’ As an educator who taught for 15 years in the public school system, this week’s news made me meditate on my own experiences of school lockdown drills that have become necessary, how I have seen them affect me, my colleagues, and our students.”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, October 29, 2025

The Case for Strip Malls, the Antidote to Shiny, Soulless City Luxury

Ismail Muhammad in the New York Times:

We’ve moved beyond what the magazine n+1 identified as the unadorned qualities of post-2008 cityscapes. That insubstantial, flat and gray “fast-casual modernism” is complemented by a social-media-approved cookie-cutter skin that has been thrust upon our major and midsize cities in a dismal consensus. It’s no surprise that New York is getting its very own versions of two neo-yuppie Los Angeles mainstays: the meme-ified health-food store Erewhon and the Los Feliz cafe Maru (which I love, of course). America’s two largest cities have most quickly been reshaped by the internet, succumbing to an epidemic of increasingly blank streets for the moneyed classes, the bicoastal and the terminally online people who covet luxury. It’s possible now to walk down Columbus Avenue and mistake it for Abbot Kinney in Venice Beach.

We’ve moved beyond what the magazine n+1 identified as the unadorned qualities of post-2008 cityscapes. That insubstantial, flat and gray “fast-casual modernism” is complemented by a social-media-approved cookie-cutter skin that has been thrust upon our major and midsize cities in a dismal consensus. It’s no surprise that New York is getting its very own versions of two neo-yuppie Los Angeles mainstays: the meme-ified health-food store Erewhon and the Los Feliz cafe Maru (which I love, of course). America’s two largest cities have most quickly been reshaped by the internet, succumbing to an epidemic of increasingly blank streets for the moneyed classes, the bicoastal and the terminally online people who covet luxury. It’s possible now to walk down Columbus Avenue and mistake it for Abbot Kinney in Venice Beach.

As a solution, I present a hated staple of American urban infrastructure: the strip mall.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

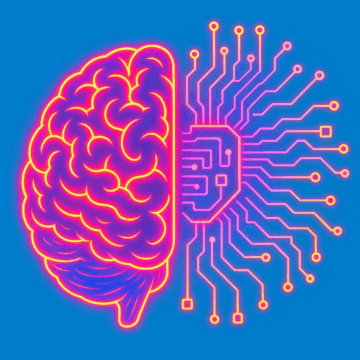

Cognitivism prevents us from understanding artificial intelligence

Paper by Mehdi Bugallo:

Cognitivism, which has permeated society—as evidenced by the omnipresence of the terms “cognitive” and “cognition”—has perpetuated a traditional view of thought and intelligence as phenomena of inextricable complexity, and therefore phenomena that we can hardly imagine recreating artificially. This approach has prevented us from anticipating and continues to prevent us from understanding what is happening. Behaviorism, on the other hand, allows us to apprehend complexity through the simple processes from which it emerges and provides the framework for understanding current AI. According to this approach, here is what is essential to understand about psychology: the environment shapes the behavior of organisms via two processes, natural selection and associative learning; the first process structures the brain over generations, establishing a “pre-wiring” that provides the basis upon which the second process structures behaviors over the course of the individual’s life.

Cognitivism, which has permeated society—as evidenced by the omnipresence of the terms “cognitive” and “cognition”—has perpetuated a traditional view of thought and intelligence as phenomena of inextricable complexity, and therefore phenomena that we can hardly imagine recreating artificially. This approach has prevented us from anticipating and continues to prevent us from understanding what is happening. Behaviorism, on the other hand, allows us to apprehend complexity through the simple processes from which it emerges and provides the framework for understanding current AI. According to this approach, here is what is essential to understand about psychology: the environment shapes the behavior of organisms via two processes, natural selection and associative learning; the first process structures the brain over generations, establishing a “pre-wiring” that provides the basis upon which the second process structures behaviors over the course of the individual’s life.

The idea of artificial neural networks functioning on associative principles is fundamentally simple, and it is not new (Geoffrey Hinton had been working on this idea for decades when he received the Nobel Prize in 2024). But for such a system to yield results, it needed to be able to integrate billions of parameters, something that was only possible with current graphics cards (GPUs); hence the sudden improvement in AI.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Ian McEwan & Brian Greene: Why do stories endure across centuries? What is the future of creativity in the age of artificial intelligence?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

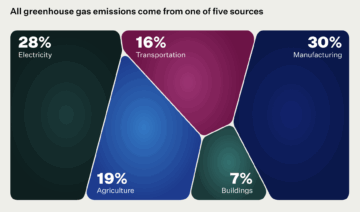

Bill Gates: Three tough truths about climate

Bill Gates at Gates Notes:

Although climate change will have serious consequences—particularly for people in the poorest countries—it will not lead to humanity’s demise. People will be able to live and thrive in most places on Earth for the foreseeable future. Emissions projections have gone down, and with the right policies and investments, innovation will allow us to drive emissions down much further.

Although climate change will have serious consequences—particularly for people in the poorest countries—it will not lead to humanity’s demise. People will be able to live and thrive in most places on Earth for the foreseeable future. Emissions projections have gone down, and with the right policies and investments, innovation will allow us to drive emissions down much further.

Unfortunately, the doomsday outlook is causing much of the climate community to focus too much on near-term emissions goals, and it’s diverting resources from the most effective things we should be doing to improve life in a warming world.

It’s not too late to adopt a different view and adjust our strategies for dealing with climate change. Next month’s global climate summit in Brazil, known as COP30, is an excellent place to begin, especially because the summit’s Brazilian leadership is putting climate adaptation and human development high on the agenda.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Philosophy of Absurdism

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

7 basic science discoveries that changed the world

Michael Marshall in Nature:

From hot springs to DNA forensics

In the summer of 1966, while he was an undergraduate at Indiana University, Hudson Freeze went to live in a cabin on the edge of Yellowstone National Park. He was working for microbiologist Thomas Brock, who was convinced that certain microorganisms were living at surprisingly high temperatures. Dodging bears, and the traffic jams they caused, Freeze visited the hot springs every day to sample their bacteria. On 19 September, Freeze succeeded in growing a sample of yellowish microbes from Mushroom Spring. Under a microscope, he found an array of cells collected from the near-boiling fluids. “I was seeing something that nobody had ever seen before,” says Freeze, now at the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California. “I still get goosebumps when I remember looking into the microscope.”

In the summer of 1966, while he was an undergraduate at Indiana University, Hudson Freeze went to live in a cabin on the edge of Yellowstone National Park. He was working for microbiologist Thomas Brock, who was convinced that certain microorganisms were living at surprisingly high temperatures. Dodging bears, and the traffic jams they caused, Freeze visited the hot springs every day to sample their bacteria. On 19 September, Freeze succeeded in growing a sample of yellowish microbes from Mushroom Spring. Under a microscope, he found an array of cells collected from the near-boiling fluids. “I was seeing something that nobody had ever seen before,” says Freeze, now at the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California. “I still get goosebumps when I remember looking into the microscope.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

The Weight of Sweetness

No easy thing to bear, the weight of sweetness.

Song, wisdom, sadness, joy: sweetness

equals three of any of these gravities.

See a peach bend

the branch and strain the stem until

it snaps.

Hold the peach, try the weight, sweetness

and death so round and snug

in your palm.

And, so, there is

the weight of memory:

Windblown, a rain-soaked

bough shakes, showering

the man and the boy.

They shiver in delight,

and the father lifts from his son’s cheek

one green leaf

fallen like a kiss.

The good boy hugs a bag of peaches

his father has entrusted to him.

Now he follows his father

who carries a bagful in each arm.

See the look on the boy’s face

as his father moves

faster, farther ahead, while his own steps

flag, his arms grow weak as he labors

under the weight

of peaches.

Li-Young Lee 1957 –

From Rose (BOA Editions, 1986).

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, October 28, 2025

Fiction as an Exercise in Sabotage

Xiaolu Guo at Words Without Borders:

A writer explores the semiotic. All artists work with signs and meanings. For me, writing is a form of semiotic sabotage. It is full of bold advances and strategic retreats, and above all it is shot through with deliberate acts of obstructionism.

A writer explores the semiotic. All artists work with signs and meanings. For me, writing is a form of semiotic sabotage. It is full of bold advances and strategic retreats, and above all it is shot through with deliberate acts of obstructionism.

But why sabotage? Why such a violent word, which resonates with political struggle and warfare?

For a storyteller who switches from one major language to another, semiotic sabotage is a means of disruption and reinvention. Often the method such an author adopts, be she a realist or a postmodernist, involves some degree of linguistic and ideological demolishing and reinventing. I am part of this phenomenon. Having left China for Britain, my writing has been a hybrid of Chinese and English linguistic forms. That’s how I imagine the possibilities of narrative.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Gordon Pennycook on Unthinkingness, Conspiracies, and What to Do About Them

Sean Carroll at Preposterous Universe:

Why are people wrong all the time, anyway? Is it because we human beings are too good at being irrational, using our biases and motivated reasoning to convince ourselves of something that isn’t quite accurate? Or is it something different — unmotivated reasoning, or “unthinkingness,” an unwillingness to do the cognitive work that most of us are actually up to if we try? Gordon Pennycook wants to argue for the latter, and this simple shift has important consequences, including for strategies for getting people to be less susceptible to misinformation and conspiracies.

Why are people wrong all the time, anyway? Is it because we human beings are too good at being irrational, using our biases and motivated reasoning to convince ourselves of something that isn’t quite accurate? Or is it something different — unmotivated reasoning, or “unthinkingness,” an unwillingness to do the cognitive work that most of us are actually up to if we try? Gordon Pennycook wants to argue for the latter, and this simple shift has important consequences, including for strategies for getting people to be less susceptible to misinformation and conspiracies.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Julian Schrittwieser: Are We Misreading the AI Exponential?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Villains on Pre-K TV Are Cuddly, Annoying and … Morally Interesting

Robin Kaiser-Schatzlein in the New York Times:

In most superhero stories, the villains are so deranged or evil that they operate outside the boundaries of society. “SuperKitties” and its ilk focus on characters who do bad things from within the boundaries of society: Their actions are hurtful or wrong, but they were committed because the character believed they were reasonable or permitted. Children may get more out of this type of character because this is exactly the kind of conflict they experience with parents, siblings and classmates; it is even a situation they may find themselves in, having done something that seemed fun or helpful only to receive a scolding, warning or lecture in response.

In most superhero stories, the villains are so deranged or evil that they operate outside the boundaries of society. “SuperKitties” and its ilk focus on characters who do bad things from within the boundaries of society: Their actions are hurtful or wrong, but they were committed because the character believed they were reasonable or permitted. Children may get more out of this type of character because this is exactly the kind of conflict they experience with parents, siblings and classmates; it is even a situation they may find themselves in, having done something that seemed fun or helpful only to receive a scolding, warning or lecture in response.

It should also be familiar to adults, who know that bad deeds can be driven by good intentions.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Plants have a secret language

Amber Dance in Nature:

When Robert Hooke gazed through his microscope at a slice of cork and coined the term ‘cell’ in 1665, he was really looking at just the walls of the dead cells. The squishy contents typically found within would become objects of ongoing study. But for many plant scientists, the walls themselves faded into the background. They were considered passive containers for the exciting biology inside.

When Robert Hooke gazed through his microscope at a slice of cork and coined the term ‘cell’ in 1665, he was really looking at just the walls of the dead cells. The squishy contents typically found within would become objects of ongoing study. But for many plant scientists, the walls themselves faded into the background. They were considered passive containers for the exciting biology inside.

“For a long time, the cell wall was really thought to be dead,” says Alice Cheung, a plant molecular biologist and biochemist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. It wasn’t until the late twentieth century, Cheung says, that scientists began to reveal the cell wall for the vibrant, ever-changing structure it is. Even then, its complex mix of sugar molecules linked into long, branching polysaccharides kept away all but the most intrepid biochemists.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.