Sheon Han at Asterisk:

The long tradition of carceral creativity goes back centuries: John Bunyan wrote The Pilgrim’s Progress, Boethius The Consolation of Philosophy, and Oscar Wilde De Profundis all while behind bars. The lineage continued into modern times with Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man, Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, and, of course, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o wrote an entire novel on toilet paper in his prison cell.

The long tradition of carceral creativity goes back centuries: John Bunyan wrote The Pilgrim’s Progress, Boethius The Consolation of Philosophy, and Oscar Wilde De Profundis all while behind bars. The lineage continued into modern times with Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man, Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, and, of course, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o wrote an entire novel on toilet paper in his prison cell.

Confinement in the military, it turns out, can also be a boon to literary output. James Salter packed a typewriter to write between flight missions, and Ludwig Wittgenstein drafted the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus in the trenches of World War I.

Because I’m no genius, writing philosophical treatises would be a tall order. But I figured I could at least read them. The bleak summer before enlistment felt less grim when I realized I could make it a reading retreat. Twenty-one months of service were ninety-one weeks — in my economy, six academic semesters, or three years of college.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

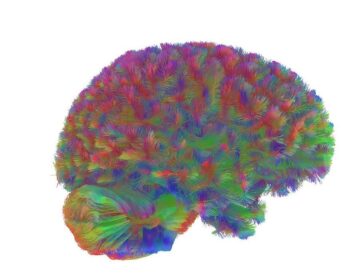

For the study, scientists combined nine previously collected datasets to look at the brain scans of almost 4,000 “neurotypical” individuals, from newborns to 90-year-olds. Specifically, they looked at diffusion MRI scans, which measure the microscopic movements of water molecules inside the brain. These scans show how the organ’s tissues are structured and can also be used to detect subtle changes, allowing the researchers to see how average brain architecture evolves over a lifetime.

For the study, scientists combined nine previously collected datasets to look at the brain scans of almost 4,000 “neurotypical” individuals, from newborns to 90-year-olds. Specifically, they looked at diffusion MRI scans, which measure the microscopic movements of water molecules inside the brain. These scans show how the organ’s tissues are structured and can also be used to detect subtle changes, allowing the researchers to see how average brain architecture evolves over a lifetime. In Jim Fishkin’s

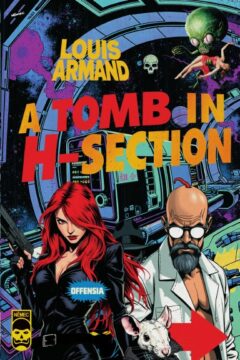

In Jim Fishkin’s  Writing à propos of Louis Armand’s recent opus magnum, A Tomb in H-Section (2025), critic Ramiro Sanchiz called it “a necromodernist tour de force which animates every remain of (un)dead XXth century literature,” thus invoking the spectre of necromodernism, a modernism long-buried but still somehow living on, its undead corpse back again for yet another zombie standoff. In a similar vein, the publisher note described the tome as “a vast, complex book object that concentrates the synergies of Louis Armand’s Golemgrad Pentalogy, of which it is at once a crowning achievement and a jocoserious deconstruction — an ‘Armandgeddon,’ if you will.”

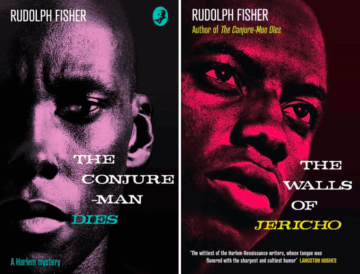

Writing à propos of Louis Armand’s recent opus magnum, A Tomb in H-Section (2025), critic Ramiro Sanchiz called it “a necromodernist tour de force which animates every remain of (un)dead XXth century literature,” thus invoking the spectre of necromodernism, a modernism long-buried but still somehow living on, its undead corpse back again for yet another zombie standoff. In a similar vein, the publisher note described the tome as “a vast, complex book object that concentrates the synergies of Louis Armand’s Golemgrad Pentalogy, of which it is at once a crowning achievement and a jocoserious deconstruction — an ‘Armandgeddon,’ if you will.” “Let Paul Robeson singing Water Boy and Rudolph Fisher writing about the streets of Harlem … cause the smug Negro middle class to turn from their white, respectable, ordinary books and papers to catch a glimmer of their own beauty.” So wrote Langston Hughes in his landmark 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” Today, Paul Robeson—singer, actor, athlete, lawyer, antiracism icon—needs no introduction. But who was Rudolph Fisher?

“Let Paul Robeson singing Water Boy and Rudolph Fisher writing about the streets of Harlem … cause the smug Negro middle class to turn from their white, respectable, ordinary books and papers to catch a glimmer of their own beauty.” So wrote Langston Hughes in his landmark 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” Today, Paul Robeson—singer, actor, athlete, lawyer, antiracism icon—needs no introduction. But who was Rudolph Fisher? A

A  We live in a world created by capitalism. The ceaseless accumulation of capital forges the cities we inhabit, determines the way we work, allows an extraordinarily large number of people to engage in unprecedented levels of consumption, influences our politics, and shapes the landscapes around us. It is impossible to look at Earth and miss the world‑historical force of capitalism.

We live in a world created by capitalism. The ceaseless accumulation of capital forges the cities we inhabit, determines the way we work, allows an extraordinarily large number of people to engage in unprecedented levels of consumption, influences our politics, and shapes the landscapes around us. It is impossible to look at Earth and miss the world‑historical force of capitalism. In mathematics,

In mathematics,  M

M Standing in a garden on the remote German island of Helgoland one day in June, two theoretical physicists quibble over who—or what—constructs reality. Carlo Rovelli, based at Aix-Marseille University, insists he is real with respect to a stone on the ground. He may cast a shadow on the stone, for instance, projecting his existence onto their relationship. Chris Fuchs of the University of Massachusetts Boston retorts that it’s preposterous to imagine the stone possessing any worldview, seeing as it is a stone. Although allied in their belief that reality is subjective rather than absolute, they both leave the impromptu debate unsatisfied, disagreeing about whether they agree.

Standing in a garden on the remote German island of Helgoland one day in June, two theoretical physicists quibble over who—or what—constructs reality. Carlo Rovelli, based at Aix-Marseille University, insists he is real with respect to a stone on the ground. He may cast a shadow on the stone, for instance, projecting his existence onto their relationship. Chris Fuchs of the University of Massachusetts Boston retorts that it’s preposterous to imagine the stone possessing any worldview, seeing as it is a stone. Although allied in their belief that reality is subjective rather than absolute, they both leave the impromptu debate unsatisfied, disagreeing about whether they agree. Fall marks the start of Iran’s rainy season, but large parts of the country have

Fall marks the start of Iran’s rainy season, but large parts of the country have