Not About Anyone’s Hands

This poem is not about anyone’s hands

holding a book or a steering wheel or winding a clock

or steady as the dark beyond my headlights.

Trees sweep past. Houses are bulk and shadow

except for a light that shows where the kitchen is. People asleep

don’t hear sorrows piling, cumulous, behind the rotting barn.

Even the air has nothing in it. This poem is not

about neighbors, or what it means to stop at a house

because all the lights are on and that means someone’s sick.

Some people driving home know just what’s in the dark:

dogs, coyotes, cows that shift against other cow legs and rumps,

tails winding down like broken metronomes

|until even the horses are dreaming, uninterrupted green.

In this poem, the wife’s hands let go of everything. Autumn glides by

outside the frost-starred, shatter-starred windshield glass.

The driveway’s long. The husband stands, watching the stars

fall doubled into the pond. He doesn’t say anything.

He doesn’t see what her arms will carry. The dogs howl.

Some things are nobody’s fault. Get the broom out.

Think of it as a waltz, dance with it, and sweep.

JoLee G. Passerini

—from Rattle #26, Winter 2006

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A

A A MAN LOOKS OVER A FENCE, SPYING. He notes the arrival of a Buick hardtop convertible. Parked now, the driver rolls the top down, using a new automatic mechanism, exposing the interior leather to the elements right at the wrong moment. The camera at first shows a magnificent three, who spill out as from a clown car: Jane Freilicher, Frank O’Hara, and John Ashbery. Then it lands on Jimmy Schuyler in the back, who, doubling as a porter, carries the luggage.

A MAN LOOKS OVER A FENCE, SPYING. He notes the arrival of a Buick hardtop convertible. Parked now, the driver rolls the top down, using a new automatic mechanism, exposing the interior leather to the elements right at the wrong moment. The camera at first shows a magnificent three, who spill out as from a clown car: Jane Freilicher, Frank O’Hara, and John Ashbery. Then it lands on Jimmy Schuyler in the back, who, doubling as a porter, carries the luggage. In 1931, at the age of forty-one, Ludwig Wittgenstein mused in his diary that perhaps his name would live on only as the end point of Western philosophy—“like the name of the one who burnt down the library of Alexandria.” There probably was no such an arsonist. The books of ancient Alexandria seem to have perished mainly by rot and neglect, not in a single blaze.

In 1931, at the age of forty-one, Ludwig Wittgenstein mused in his diary that perhaps his name would live on only as the end point of Western philosophy—“like the name of the one who burnt down the library of Alexandria.” There probably was no such an arsonist. The books of ancient Alexandria seem to have perished mainly by rot and neglect, not in a single blaze. Social Text still exists.

Social Text still exists. The four most advanced AI systems are

The four most advanced AI systems are

A

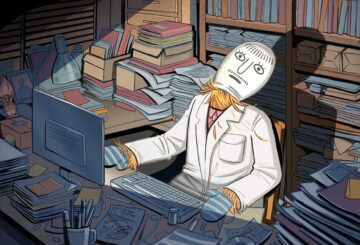

A Beatriz Ychussie’s career in mathematics seemed to be going really well. She worked at Roskilde University in Denmark where, in 2015 and 2016 alone, she published four papers on mathematical formulae for quantum particles, heat flow and geometry, and reviewed multiple manuscripts for reputable journals. But a few years later, her run of promising studies dried up. An investigation by the publisher of three of those papers found not only that the work was flawed, but that Ychussie didn’t even exist.

Beatriz Ychussie’s career in mathematics seemed to be going really well. She worked at Roskilde University in Denmark where, in 2015 and 2016 alone, she published four papers on mathematical formulae for quantum particles, heat flow and geometry, and reviewed multiple manuscripts for reputable journals. But a few years later, her run of promising studies dried up. An investigation by the publisher of three of those papers found not only that the work was flawed, but that Ychussie didn’t even exist. T

T The trajectory of intelligent life on this planet can be described as an evolution of its verbs: to move, to reproduce, to hunt, to hide, to feel, to make, to use, to think. With the recent rise of artificial intelligence and competent chatbots, many experts have volubly opined about which verbs matter for what counts as “intelligence.” But like artificial insemination, artificial hearts, and artificial reefs, artificial intelligence was designed to interface with biology; its abilities and purpose are inferred exclusively from this interaction.

The trajectory of intelligent life on this planet can be described as an evolution of its verbs: to move, to reproduce, to hunt, to hide, to feel, to make, to use, to think. With the recent rise of artificial intelligence and competent chatbots, many experts have volubly opined about which verbs matter for what counts as “intelligence.” But like artificial insemination, artificial hearts, and artificial reefs, artificial intelligence was designed to interface with biology; its abilities and purpose are inferred exclusively from this interaction. During the 2018 election, Americans – candidates, parties, PACs, and small donors like you – spent a combined $5 billion pushing their preferred candidates. Although that sounds like a lot of money, Americans spent $12 billion on almonds that same year. Why the imbalance? The oil industry has strong political opinions, and they make $500 billion per year. Do they really think electing oil-friendly politicians isn’t worth 2% of revenue?

During the 2018 election, Americans – candidates, parties, PACs, and small donors like you – spent a combined $5 billion pushing their preferred candidates. Although that sounds like a lot of money, Americans spent $12 billion on almonds that same year. Why the imbalance? The oil industry has strong political opinions, and they make $500 billion per year. Do they really think electing oil-friendly politicians isn’t worth 2% of revenue? We are naturally a highly violent species with a thin veneer of civilization that masks a brutal proclivity for violence – or so many people think. In the seventeenth century, Thomas Hobbes said that human life without government is ‘solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short’. William Golding’s novel, The Lord of the Flies, which helped him win the Nobel Prize for literature in 1983 and many of us read in school, suggests that boys will rapidly descend into mob violence and brutal cruelty without oversight from authority. To know whether this is true, we need to understand the rates of violence among our ancestors.

We are naturally a highly violent species with a thin veneer of civilization that masks a brutal proclivity for violence – or so many people think. In the seventeenth century, Thomas Hobbes said that human life without government is ‘solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short’. William Golding’s novel, The Lord of the Flies, which helped him win the Nobel Prize for literature in 1983 and many of us read in school, suggests that boys will rapidly descend into mob violence and brutal cruelty without oversight from authority. To know whether this is true, we need to understand the rates of violence among our ancestors.