Tim Adams in The Guardian:

He begins with Rousseau, and in particular his 1755 Discourse on Inequality, the Swiss philosopher’s entry to an essay competition run by the Academy of Dijon – a sort of Enlightenment France Has Got Talent – that addressed how we ended up in a world in which “an imbecile should lead a wise man, and a handful of people should gorge themselves on superfluities while the hungry multitude goes in want of necessities”. Briskly examining Jean-Jacques’s rewind into human prehistory to explain this state of affairs, Runciman is able to collapse certain myths, not least that persistent idea that Rousseau was the “friendly” and “natural” philosopher, the first hippy, the consummate rewilder, by reminding the reader that so indifferent was he to the “artificial” and “constraining” bonds of society, that he put all his five children into a foundling home, dramatising his belief that even family ties were a “sham”, and that the individual and his relationship with nature was all that counted.

He begins with Rousseau, and in particular his 1755 Discourse on Inequality, the Swiss philosopher’s entry to an essay competition run by the Academy of Dijon – a sort of Enlightenment France Has Got Talent – that addressed how we ended up in a world in which “an imbecile should lead a wise man, and a handful of people should gorge themselves on superfluities while the hungry multitude goes in want of necessities”. Briskly examining Jean-Jacques’s rewind into human prehistory to explain this state of affairs, Runciman is able to collapse certain myths, not least that persistent idea that Rousseau was the “friendly” and “natural” philosopher, the first hippy, the consummate rewilder, by reminding the reader that so indifferent was he to the “artificial” and “constraining” bonds of society, that he put all his five children into a foundling home, dramatising his belief that even family ties were a “sham”, and that the individual and his relationship with nature was all that counted.

At the other “bracing” extreme from Rousseau he argues that Nietzsche, another great unraveller of human political DNA, comes at the “how the hell did we get here?” question from the diametrically opposed position: not “how did the privileged few come to dominate the many” but how did the many, through religion and democracy, come to dominate the few, the elite, the powerful, their true masters?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A group of nine mathematicians has proved the geometric Langlands conjecture, a key component of one of the most sweeping paradigms in modern mathematics.

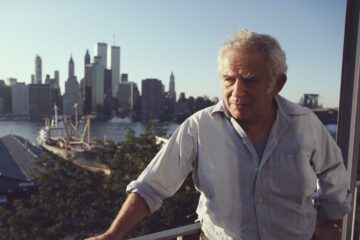

A group of nine mathematicians has proved the geometric Langlands conjecture, a key component of one of the most sweeping paradigms in modern mathematics. Western intellectuals expected that novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, once safely in the West after his expulsion from the Soviet Union in 1974, would enthusiastically endorse its way of life and intellectual consensus. Nothing of the sort happened. Instead of recognizing how much he had missed when cut off from New York, Washington, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, this ex-Soviet dissident not only refused to accept superior American ideas but even presumed to instruct us. Harvard was shocked at the speech he gave there in 1978, while the New York Times cautioned: “We fear that Mr. Solzhenitsyn does the world no favor by calling for a holy war.”

Western intellectuals expected that novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, once safely in the West after his expulsion from the Soviet Union in 1974, would enthusiastically endorse its way of life and intellectual consensus. Nothing of the sort happened. Instead of recognizing how much he had missed when cut off from New York, Washington, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, this ex-Soviet dissident not only refused to accept superior American ideas but even presumed to instruct us. Harvard was shocked at the speech he gave there in 1978, while the New York Times cautioned: “We fear that Mr. Solzhenitsyn does the world no favor by calling for a holy war.” I

I  Not so long ago, a friend texted me from a coffee shop. He said, “I can’t believe it. I’m the only one here without a tattoo!” That might not seem surprising: a quick glance around practically anywhere people gather shows that tattoos are widely popular. Nearly one-third of adults in the US have a tattoo, according to

Not so long ago, a friend texted me from a coffee shop. He said, “I can’t believe it. I’m the only one here without a tattoo!” That might not seem surprising: a quick glance around practically anywhere people gather shows that tattoos are widely popular. Nearly one-third of adults in the US have a tattoo, according to  Alcove 1 at the City College of New York is surely the most famous lunch table in American intellectual history. No Ivy League dining hall can compete. In the 1930s, a remarkable coterie of students gathered there. (The neighboring alcove, Alcove 2, was a meeting place for students who hewed closer to the party line in Moscow, for the “Stalinists” as they would have been called in Alcove 1.) By now many books and documentaries have been made and written about Alcove 1 and its legacy, which in miniature is the saga of the “New York intellectuals.” They were mostly Jewish, uniformly gifted, and fabulously influential at midcentury. Their history can have the aura of myth.

Alcove 1 at the City College of New York is surely the most famous lunch table in American intellectual history. No Ivy League dining hall can compete. In the 1930s, a remarkable coterie of students gathered there. (The neighboring alcove, Alcove 2, was a meeting place for students who hewed closer to the party line in Moscow, for the “Stalinists” as they would have been called in Alcove 1.) By now many books and documentaries have been made and written about Alcove 1 and its legacy, which in miniature is the saga of the “New York intellectuals.” They were mostly Jewish, uniformly gifted, and fabulously influential at midcentury. Their history can have the aura of myth. Its canonical status is hardly in doubt, but at the same time, 20 years after its publication, “The Known World” can still feel like a discovery. Even a rereading propels you into uncharted territory. You may think you know about American slavery, about the American novel, about the American slavery novel, but here is something you couldn’t have imagined, a secret history hidden in plain sight. The author occupies a similarly paradoxical status: He’s a major writer, yet somehow underrecognized. This may be partly because he doesn’t call much attention to himself, and partly because of his compact output. (When I asked, he said he wasn’t working on anything new at the moment, though there was a story that had been gestating for a while.) Jones, who teaches creative writing at George Washington University, is not a recluse, but he’s not a public figure either. Our meeting place was his idea.

Its canonical status is hardly in doubt, but at the same time, 20 years after its publication, “The Known World” can still feel like a discovery. Even a rereading propels you into uncharted territory. You may think you know about American slavery, about the American novel, about the American slavery novel, but here is something you couldn’t have imagined, a secret history hidden in plain sight. The author occupies a similarly paradoxical status: He’s a major writer, yet somehow underrecognized. This may be partly because he doesn’t call much attention to himself, and partly because of his compact output. (When I asked, he said he wasn’t working on anything new at the moment, though there was a story that had been gestating for a while.) Jones, who teaches creative writing at George Washington University, is not a recluse, but he’s not a public figure either. Our meeting place was his idea. The Earth’s oceans remain a source of anxious uncertainty. For all that we’ve chartered upon the waves of the sea, that which lies beneath remains as dark as the impenetrable barriers through which surface light does not penetrate, a black kingdom of translucent glowing fish with jagged deaths-teeth and of massive worms living in volcanic trenches. More than even interstellar space, the ocean’s uncanniness disrupts because the entrance to this unknown empire is as near as the closest beach, where even on the sunniest days a consideration of what hides below can give a sense of what the horror author H.P. Lovecraft wrote in a 1927 essay from The Recluse, when he claimed that the “oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is a fear of the unknown.” The conjuring of that emotion was a motivating impulse in Lovecraft’s weird fiction, in which he imagined such horrors as the “elder god” Cthulhu, a massive, uncaring, and nearly immortal alien cephalopod imprisoned in the ancient sunken city of R’lyeh, located approximately 50 degrees south and 100 degrees west.

The Earth’s oceans remain a source of anxious uncertainty. For all that we’ve chartered upon the waves of the sea, that which lies beneath remains as dark as the impenetrable barriers through which surface light does not penetrate, a black kingdom of translucent glowing fish with jagged deaths-teeth and of massive worms living in volcanic trenches. More than even interstellar space, the ocean’s uncanniness disrupts because the entrance to this unknown empire is as near as the closest beach, where even on the sunniest days a consideration of what hides below can give a sense of what the horror author H.P. Lovecraft wrote in a 1927 essay from The Recluse, when he claimed that the “oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is a fear of the unknown.” The conjuring of that emotion was a motivating impulse in Lovecraft’s weird fiction, in which he imagined such horrors as the “elder god” Cthulhu, a massive, uncaring, and nearly immortal alien cephalopod imprisoned in the ancient sunken city of R’lyeh, located approximately 50 degrees south and 100 degrees west. The inspiration for the titular device in last year’s blockbuster,

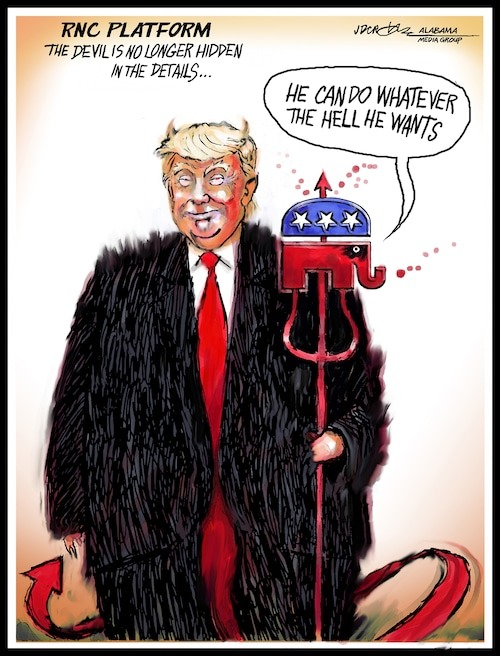

The inspiration for the titular device in last year’s blockbuster,  It can be a comfort and consolation to believe one’s political opponents don’t really mean what they say. They’re liars. Hypocrites. Shameless opportunists who will say and do anything to gain power. It’s impossible to take them seriously.

It can be a comfort and consolation to believe one’s political opponents don’t really mean what they say. They’re liars. Hypocrites. Shameless opportunists who will say and do anything to gain power. It’s impossible to take them seriously. W

W T

T Henry Grabar has had enough

Henry Grabar has had enough