Ed Simon at Lit Hub:

My desire to write a cultural history of the Faust legend goes back a few years earlier than my pilgrimage to the Deptford churchyard, around the time that I attended an adaptation of the play entitled faustUS staged by the theater collective 404 Strand in my hometown of Pittsburgh. Basing the script on the shorter, so-called “Text A” of Marlowe’s play, a tauter and more cryptic work that cuts the slapstick that mars more traditional productions of Doctor Faustus, the performance was hallucinatory, ritualistic, psychedelic, incantatory. A work of conjuration. With the audience invited to sit in an ad hoc theater-in-the-round constructed on the stage of the Kelly Strayhorn Theater, we all faced a rusted iron-cage in which the action of the play would be set. I was in the front row.

My desire to write a cultural history of the Faust legend goes back a few years earlier than my pilgrimage to the Deptford churchyard, around the time that I attended an adaptation of the play entitled faustUS staged by the theater collective 404 Strand in my hometown of Pittsburgh. Basing the script on the shorter, so-called “Text A” of Marlowe’s play, a tauter and more cryptic work that cuts the slapstick that mars more traditional productions of Doctor Faustus, the performance was hallucinatory, ritualistic, psychedelic, incantatory. A work of conjuration. With the audience invited to sit in an ad hoc theater-in-the-round constructed on the stage of the Kelly Strayhorn Theater, we all faced a rusted iron-cage in which the action of the play would be set. I was in the front row.

My most distinctive memory of that performance was the actor who played Faust, shirtless and sinewy, glistening with sweat beneath the oppressive stage lights, hoisting a shaggy, bestial mask of a horn-twisted ox over his head, and wildly gesticulating to thrash metal so loud that my fillings were humming, the necromancer then taking a full loaf of white bread out of its antiseptic bag and shredding it into the gapping maw of the bovine mask, bits of spongy whiteness spraying onto all of us sitting in the front row.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

If you ask Bette Midler how she got her part in the new film The Fabulous Four, it wouldn’t have anything to do with her legendary status as a performer, or that she’s an Oscar-nominated actor. “I think they needed a ham, a big ole ham. So, I got that part.” Midler plays Marilyn, a widow getting remarried who rekindles a friendship with her three college girlfriends, played by Susan Sarandon, Sheryl Lee Ralph and Megan Mullally. “No actor doesn’t like to chew the scenery, even if they don’t admit it. So, to have the permission to pull out all the stops is always great.” What was also great was working with her three costars. “Working with these these girls…girls, girls, oh my God, we’re 100! These women! Working with these women was really an eye-opener because everybody’s process is different.”

If you ask Bette Midler how she got her part in the new film The Fabulous Four, it wouldn’t have anything to do with her legendary status as a performer, or that she’s an Oscar-nominated actor. “I think they needed a ham, a big ole ham. So, I got that part.” Midler plays Marilyn, a widow getting remarried who rekindles a friendship with her three college girlfriends, played by Susan Sarandon, Sheryl Lee Ralph and Megan Mullally. “No actor doesn’t like to chew the scenery, even if they don’t admit it. So, to have the permission to pull out all the stops is always great.” What was also great was working with her three costars. “Working with these these girls…girls, girls, oh my God, we’re 100! These women! Working with these women was really an eye-opener because everybody’s process is different.” A climate scientist who was demoted for speaking out by the administration of former US president Donald Trump is seeking an investigation into her case and demanding changes to personnel policies to prevent similar retaliation against others in future. Her supporters say the proposed reforms could help her agency, the US Geological Survey (USGS), as well as others safeguard science in the event of a second Trump administration, which many fear will be even more efficient than the first at

A climate scientist who was demoted for speaking out by the administration of former US president Donald Trump is seeking an investigation into her case and demanding changes to personnel policies to prevent similar retaliation against others in future. Her supporters say the proposed reforms could help her agency, the US Geological Survey (USGS), as well as others safeguard science in the event of a second Trump administration, which many fear will be even more efficient than the first at  L

L Sixty-five years ago, on July 17, 1959, Billie Holiday died at Metropolitan Hospital in New York. The 44-year-old singer arrived after being turned away from a nearby charity hospital on evidence of drug use, then lay for hours on a stretcher in the hallway,

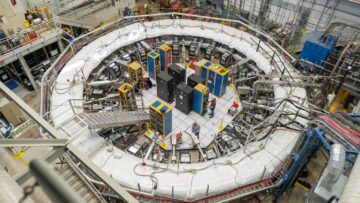

Sixty-five years ago, on July 17, 1959, Billie Holiday died at Metropolitan Hospital in New York. The 44-year-old singer arrived after being turned away from a nearby charity hospital on evidence of drug use, then lay for hours on a stretcher in the hallway,  Perhaps the greatest quest in particle physics, for perhaps half a century now, has been to find a discrepancy between theory and experiment when it comes to the Standard Model. One fascinating place to look is at the magnetic moment of the muon: a heavy, unstable relative of the electron. A Fermilab experiment known as

Perhaps the greatest quest in particle physics, for perhaps half a century now, has been to find a discrepancy between theory and experiment when it comes to the Standard Model. One fascinating place to look is at the magnetic moment of the muon: a heavy, unstable relative of the electron. A Fermilab experiment known as  Last Tuesday, President Biden signed into law America’s first comprehensive nuclear energy bill

Last Tuesday, President Biden signed into law America’s first comprehensive nuclear energy bill  T

T America currently finds itself in

America currently finds itself in  Anthe (ಅಂತೆ) is one of my favorite words in the Kannada language. Somewhat meaningless by itself, it adds so much nuance and emotion when appended to a sentence that we Kannadigas cannot carry on a conversation without using it. Depending on the context and the speaker’s tone, anthe can convey an expression of surprise or the understanding that gossip is being shared. It could mean “so it happened,” “that’s how it is,” “apparently,” or “it seems.” The latter comes closest to a direct translation, but is a frustratingly simple choice. Anthe will only ever half-heartedly migrate to English. Banu Mushtaq, whose short stories I have been translating recently, and whose “

Anthe (ಅಂತೆ) is one of my favorite words in the Kannada language. Somewhat meaningless by itself, it adds so much nuance and emotion when appended to a sentence that we Kannadigas cannot carry on a conversation without using it. Depending on the context and the speaker’s tone, anthe can convey an expression of surprise or the understanding that gossip is being shared. It could mean “so it happened,” “that’s how it is,” “apparently,” or “it seems.” The latter comes closest to a direct translation, but is a frustratingly simple choice. Anthe will only ever half-heartedly migrate to English. Banu Mushtaq, whose short stories I have been translating recently, and whose “ Eitan Hersh: I think that the way that 95% of people who are engaged in politics are engaged is not really politics. It’s like if we imagine that all football fans were actually football players. Of about a third of the country that pays attention to politics, nearly all of them are just engaging for some sort of emotional connection or for intellectual gratification. They want to learn stuff. And they’re not building the right skills or getting the right knowledge for them to inform votes or activism. They’re just doing a totally different thing.

Eitan Hersh: I think that the way that 95% of people who are engaged in politics are engaged is not really politics. It’s like if we imagine that all football fans were actually football players. Of about a third of the country that pays attention to politics, nearly all of them are just engaging for some sort of emotional connection or for intellectual gratification. They want to learn stuff. And they’re not building the right skills or getting the right knowledge for them to inform votes or activism. They’re just doing a totally different thing. The great discoveries of humanity have always taught us that we are not masters in our own house: Copernicus removed the Earth from the centre of the cosmos, Darwin spoiled our species’ idea of divine creation, Freud showed that we neither know nor control our desires. The humiliation by AI is subtler but just as profound: we have demonstrated that for intellectual activities we considered deeply human, we are not needed; these can be automated on a statistical basis, the “idle talk”, to use Heidegger’s term, literally gets by without us and sounds reasonable, witty, superficial and sympathetic – and only then do we truly understand that it has always been like this: most of the time, we communicate on autopilot.

The great discoveries of humanity have always taught us that we are not masters in our own house: Copernicus removed the Earth from the centre of the cosmos, Darwin spoiled our species’ idea of divine creation, Freud showed that we neither know nor control our desires. The humiliation by AI is subtler but just as profound: we have demonstrated that for intellectual activities we considered deeply human, we are not needed; these can be automated on a statistical basis, the “idle talk”, to use Heidegger’s term, literally gets by without us and sounds reasonable, witty, superficial and sympathetic – and only then do we truly understand that it has always been like this: most of the time, we communicate on autopilot.