Rachelle Bergstein at Literary Hub:

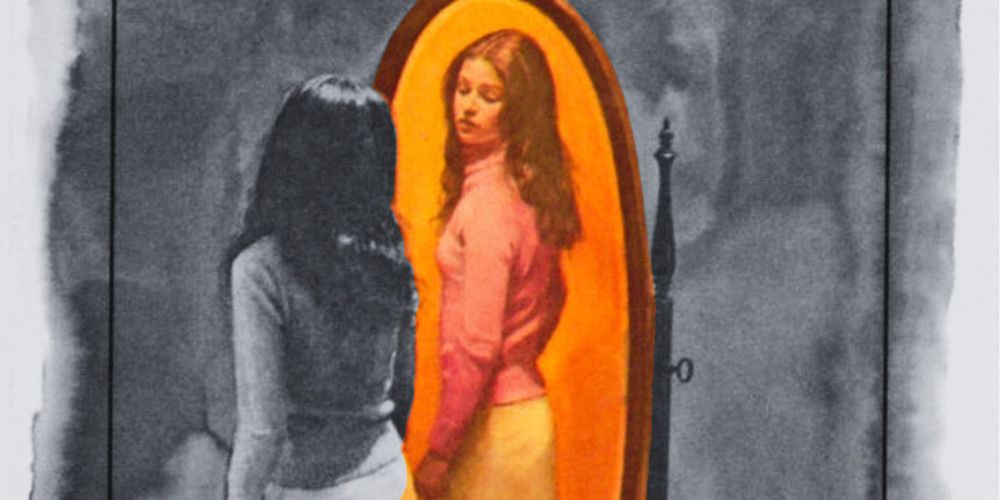

Like many adolescents, Deenie has a secret.

Like many adolescents, Deenie has a secret.

Or maybe “secret” isn’t the right word. Deenie has a private ritual, something she does when she can’t sleep. She doesn’t know why, but it makes her feel better. Touching her “special place” helps stave off her worries. Or, as she puts it, “I have this special place and when I rub it I get a very nice feeling.”

Let’s be clear—until Judy Blume’s 1973 novel Deenie, girls didn’t masturbate in children’s literature. Inventive, now classic characters like Pippi Longstocking and Ramona Quimby were zany and unpredictable, but they certainly never told us where their hands wandered when they were alone. Even now, the mention of self-pleasure in a young adult book is enough to get it yanked from school libraries.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

This notion — that LLMs are “just” next-word predictors based on statistical models of text — is so common now as to be almost a trope. It is used, both correctly and incorrectly, to explain the flaws, biases, and other limitations of LLMs. Most importantly, it is used by AI skeptics like [Gary] Marcus to argue that there will soon be

This notion — that LLMs are “just” next-word predictors based on statistical models of text — is so common now as to be almost a trope. It is used, both correctly and incorrectly, to explain the flaws, biases, and other limitations of LLMs. Most importantly, it is used by AI skeptics like [Gary] Marcus to argue that there will soon be  Qamar-ul Huda opens the first chapter of his new book Reenvisioning Peacebuilding and Conflict Resolution in Islam with the differing American and Norwegian approaches to Afghanistan, illustrating how international efforts to end wars and support peace in Muslim countries can be successful, especially when conducted on Islamic terms.

Qamar-ul Huda opens the first chapter of his new book Reenvisioning Peacebuilding and Conflict Resolution in Islam with the differing American and Norwegian approaches to Afghanistan, illustrating how international efforts to end wars and support peace in Muslim countries can be successful, especially when conducted on Islamic terms. As a musician, Charli XCX was born online. Her first album circulated via CD-Rs and MySpace when the artist was just fourteen. Journalists love to drop this detail, but seldom do they follow up on how this ever-shifting www. vernacular inflects her songwriting style. Her compositions often hinge on the repetition of single words or phrases, like “focus,” “airport,” or “number one.” Syncopation spins the familiar into an earworm, disarticulating the very meaning of a lyric into a melodic vibe. After a couple of major-label albums failed to connect, Charli saw promise in how this approach might marry with the emergent underground PC

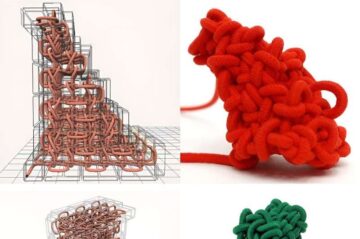

As a musician, Charli XCX was born online. Her first album circulated via CD-Rs and MySpace when the artist was just fourteen. Journalists love to drop this detail, but seldom do they follow up on how this ever-shifting www. vernacular inflects her songwriting style. Her compositions often hinge on the repetition of single words or phrases, like “focus,” “airport,” or “number one.” Syncopation spins the familiar into an earworm, disarticulating the very meaning of a lyric into a melodic vibe. After a couple of major-label albums failed to connect, Charli saw promise in how this approach might marry with the emergent underground PC  Yuichi Hirose has a dream—a dream that someday everyone will have access to a machine capable of knitting furniture.

Yuichi Hirose has a dream—a dream that someday everyone will have access to a machine capable of knitting furniture. Simply put, downtowns matter less and less. In Austin and elsewhere, we are witnessing an epochal shift away from the highly concentrated urban center first described by Jean Gottmann in 1983 as the “

Simply put, downtowns matter less and less. In Austin and elsewhere, we are witnessing an epochal shift away from the highly concentrated urban center first described by Jean Gottmann in 1983 as the “ Every so often someone writes an essay with a title like “Against Travel,” “The Case for Staying on One’s Couch,” or “Germans in Sweatpants: Why Going Places Was a Mistake.” Such pieces usually go viral, since they appeal to the two itches few readers seem able to resist scratching—the itch to be agreed with and the itch to be mad at a stranger. I always root for the writers of these pieces. I want them to win the impossible fight they’ve picked.

Every so often someone writes an essay with a title like “Against Travel,” “The Case for Staying on One’s Couch,” or “Germans in Sweatpants: Why Going Places Was a Mistake.” Such pieces usually go viral, since they appeal to the two itches few readers seem able to resist scratching—the itch to be agreed with and the itch to be mad at a stranger. I always root for the writers of these pieces. I want them to win the impossible fight they’ve picked. If there’s one phrase the June 2024 U.S. presidential debate may entirely eliminate from the English vocabulary it’s that age is a meaningless number. Often attributed to boxer

If there’s one phrase the June 2024 U.S. presidential debate may entirely eliminate from the English vocabulary it’s that age is a meaningless number. Often attributed to boxer  In 2016, a historically unprecedented incident took place. And yet, barely anyone even noticed. Even years later, we’ve failed to acknowledge it or to have begun the process of understanding it. Because we still can’t even see it.

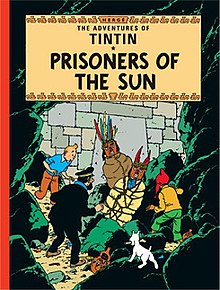

In 2016, a historically unprecedented incident took place. And yet, barely anyone even noticed. Even years later, we’ve failed to acknowledge it or to have begun the process of understanding it. Because we still can’t even see it. When Tintin is captured by an ancient Inca tribe in his fourteenth adventure, Prisoners of the Sun, he finds an article on his cell floor that forecasts a coming solar eclipse. This will prove to be significant since he, Captain Haddock, and Professor Calculus are to be burned at the stake. Tintin manages to see to it that the execution is staged at the right moment. When the Inca Prince of the Sun orders the pyre to be lit, Tintin invokes the Sun God: “O God of the Sun, sublime Pachacamac, display thy power, I implore thee! … If this sacrifice is not thy will, hide thy shining face from us!” In this patronizing Occidental fable of mathematical calculation triumphing over traditional belief, the weather god gives way to the scientist, whose knowledge gives Tintin the power to produce an apparent miracle.

When Tintin is captured by an ancient Inca tribe in his fourteenth adventure, Prisoners of the Sun, he finds an article on his cell floor that forecasts a coming solar eclipse. This will prove to be significant since he, Captain Haddock, and Professor Calculus are to be burned at the stake. Tintin manages to see to it that the execution is staged at the right moment. When the Inca Prince of the Sun orders the pyre to be lit, Tintin invokes the Sun God: “O God of the Sun, sublime Pachacamac, display thy power, I implore thee! … If this sacrifice is not thy will, hide thy shining face from us!” In this patronizing Occidental fable of mathematical calculation triumphing over traditional belief, the weather god gives way to the scientist, whose knowledge gives Tintin the power to produce an apparent miracle. JOHN TOOBY (July 26, 1952-November 9, 2023) was the founder of the field of Evolutionary Psychology, co-director (with his wife, Leda Cosmides) of the Center for Evolutionary Psychology, and professor of anthropology at UC Santa Barbara. He received his PhD in biological anthropology from Harvard University in 1989 and was professor of anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Tooby and Cosmides also co-founded and co-directed the UCSB Center for Evolutionary Psychology and jointly received the 2020 Jean Nicod Prize.

JOHN TOOBY (July 26, 1952-November 9, 2023) was the founder of the field of Evolutionary Psychology, co-director (with his wife, Leda Cosmides) of the Center for Evolutionary Psychology, and professor of anthropology at UC Santa Barbara. He received his PhD in biological anthropology from Harvard University in 1989 and was professor of anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Tooby and Cosmides also co-founded and co-directed the UCSB Center for Evolutionary Psychology and jointly received the 2020 Jean Nicod Prize. C

C A

A The day I met Daniel Kahneman, he had asked me to join him for lunch at the Bowery Road restaurant in Lower Manhattan. Danny proposed this venue because it has comfortable booths and ‘is mostly deserted’. I arrived

The day I met Daniel Kahneman, he had asked me to join him for lunch at the Bowery Road restaurant in Lower Manhattan. Danny proposed this venue because it has comfortable booths and ‘is mostly deserted’. I arrived  The IMO is considered the world’s most prestigious competition for young mathematicians. Correctly answering its test questions requires mathematical ability that AI systems typically lack.

The IMO is considered the world’s most prestigious competition for young mathematicians. Correctly answering its test questions requires mathematical ability that AI systems typically lack.