More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

From The Christian Science Monitor:

One of this year’s most influential people on TikTok and YouTube does not see himself as an influencer. He is Thích Minh Tuệ, a middle-aged man who adopted a humble, ascetic life a few years ago and began to walk barefoot up and down Vietnam. He lived in forests with few clothes and accepted alms from strangers, practicing a Buddhist way of frugal simplicity. In May, he became an internet phenomenon. Admirers began to post videos of him along his pilgrimage, inspiring millions. While disavowing any attempt at virtue signaling, he nonetheless was widely seen as an exemplary model, especially in comparison with the lavish lifestyles of top officials. Vietnamese were particularly irked when the minister of public security was caught on camera eating gold-encrusted steak at a London restaurant three years ago. In June, at the strong advice of police, Thích Minh Tuệ disappeared from public view. “His real crime was his humble lifestyle that stands in such stark contrast to the corruption scandals that have rocked Vietnam,” wrote Zachary Abuza, professor at the National War College in Washington, for Radio Free Asia.

One of this year’s most influential people on TikTok and YouTube does not see himself as an influencer. He is Thích Minh Tuệ, a middle-aged man who adopted a humble, ascetic life a few years ago and began to walk barefoot up and down Vietnam. He lived in forests with few clothes and accepted alms from strangers, practicing a Buddhist way of frugal simplicity. In May, he became an internet phenomenon. Admirers began to post videos of him along his pilgrimage, inspiring millions. While disavowing any attempt at virtue signaling, he nonetheless was widely seen as an exemplary model, especially in comparison with the lavish lifestyles of top officials. Vietnamese were particularly irked when the minister of public security was caught on camera eating gold-encrusted steak at a London restaurant three years ago. In June, at the strong advice of police, Thích Minh Tuệ disappeared from public view. “His real crime was his humble lifestyle that stands in such stark contrast to the corruption scandals that have rocked Vietnam,” wrote Zachary Abuza, professor at the National War College in Washington, for Radio Free Asia.

Thích Minh Tuệ’s story reflects a bubbling debate among corruption fighters around the world about whether to focus less on corruption itself and more on the intrinsic integrity and honesty of people. “There have been growing calls for a renewed focus on the central role of values, ethics and integrity in controlling corruption,” stated a 2022 report by the watchdog Transparency International.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

—Before the Coming of the White man

I am the White Corn Boy

I walk in sight of my home.

I walk in plain sight of my home.

I walk on the straight path which is towards my home.

I walk to the entrance of my home.

I arrive at the beautiful goods curtain which hangs at the doorway.

I arrive at the entrance of my home.

I am in the middle of my home.

I am at the back of my home.

I am on top of the pollen footprint.

I am on top of the pollen seed print.

I am like the Most High Power Whose Ways are Beautiful.

Before me it is beautiful.

Behind me it is beautiful.

Under me it is beautiful.

Above me it is beautiful.

All around me it is beautiful.

from Aileen O’Brian, The Diné Origin Myths of the Navajo Indians

from American Indian Prose and Poetry

G.P. Putnam’s Sons, NY,1974

Ryan Nourai in Esquire:

I was sitting in a funeral home in San Pedro, California, surrounded by carpeted floors, inaudible footsteps, and clasped hands. And then—I couldn’t help it—I imagined her body ripped apart. Would the powder in the bullet explode in the flames? My body tried to jump up from the heavy green leather chair, but my mind stopped it—of course the ammunition was exhausted when the bullet was fired, twenty-eight years before. But even though I understood this intellectually, still I asked my question out loud: “Is the bullet going to explode?”

The mortician—unaware of the assault my mother had survived all those years ago, when she was kidnapped, raped, and shot—struggled to understand my panic and my question. While my mother was alive, the crimes perpetrated on her in that alley remained abstract to me—a story. I knew one fact for sure, that had the bullet been, in the words of the neurosurgeon who treated her, “a hair over,” she wouldn’t have survived. I wouldn’t have ever been born.

Why, now that she was gone, now that her body was in the next room, was the incident starting to feel closer than ever?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Michael Le Page in New Scientist:

Drinking even small amounts of alcohol reduces your life expectancy, rigorous studies show. Only those with serious flaws suggest that moderate drinking is beneficial. That’s the conclusion of a review of 107 studies looking at how drinking alcohol affects people’s risk of dying from any cause at a particular age.

Drinking even small amounts of alcohol reduces your life expectancy, rigorous studies show. Only those with serious flaws suggest that moderate drinking is beneficial. That’s the conclusion of a review of 107 studies looking at how drinking alcohol affects people’s risk of dying from any cause at a particular age.

“People need to be sceptical of the claims that the industry has fuelled over the years,” says Tim Stockwell at the University of Victoria in Canada. “They obviously have a great stake in promoting their product as something that’s going to make you live longer as opposed to one that will give you cancer.”

While the risks of moderate drinking are small, people should be told that it isn’t beneficial, says Stockwell. “It’s maybe not as risky as lots of other things you do, but it’s important that consumers are aware,” he says. “I think it’s also important that the producers are made to inform consumers of the risks through warning labels.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Musa al-Gharbi at Symbolic Capital(ism):

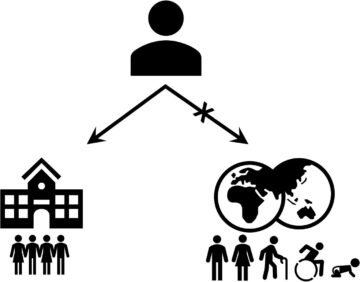

Symbolic capitalists are strange people. Actually, it might be more apt to say we are particularly WEIRD. In decades-worth of empirical studies carried out across the globe, anthropologist Joseph Henrich and his collaborators have documented many ways people from Western, Highly-Educated, Industrial, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD) societies diverge systematically from most others worldwide. For instance:

Symbolic capitalists are strange people. Actually, it might be more apt to say we are particularly WEIRD. In decades-worth of empirical studies carried out across the globe, anthropologist Joseph Henrich and his collaborators have documented many ways people from Western, Highly-Educated, Industrial, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD) societies diverge systematically from most others worldwide. For instance:

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Stephen Smith at The Guardian:

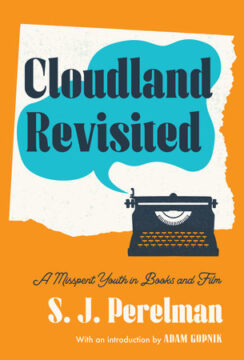

What do TS Eliot, the Coen brothers, Dorothy Parker, Mel Brooks, Clive James and Woody Allen have in common? The answer is that they all admired SJ Perelman, the droll New York prose stylist and Oscar-winning screenwriter. There’s a crowded field in the sweepstakes for the best writer you’ve never heard of, but the form book suggests that Perelman would place, at the very least. He wrote for Hollywood and the New Yorker in the middle of the 20th century, when smart, wisecracking American humour was the laughter heard across the globe. He collaborated with the Marx Brothers on Monkey Business and Horse Feathers and received his Academy Award for Around the World in 80 Days. There was an SJP bossing Manhattan when Sex and the City was just a bubble in a cosmopolitan.

What do TS Eliot, the Coen brothers, Dorothy Parker, Mel Brooks, Clive James and Woody Allen have in common? The answer is that they all admired SJ Perelman, the droll New York prose stylist and Oscar-winning screenwriter. There’s a crowded field in the sweepstakes for the best writer you’ve never heard of, but the form book suggests that Perelman would place, at the very least. He wrote for Hollywood and the New Yorker in the middle of the 20th century, when smart, wisecracking American humour was the laughter heard across the globe. He collaborated with the Marx Brothers on Monkey Business and Horse Feathers and received his Academy Award for Around the World in 80 Days. There was an SJP bossing Manhattan when Sex and the City was just a bubble in a cosmopolitan.

Now some of Perelman’s work has been republished. Cloudland Revisited: A Misspent Youth in Books and Film brings together essays in which the mature Perelman returns to the dime store novels and schlocky movies that he enjoyed in his teens.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Arwa Mahdawi in The Guardian:

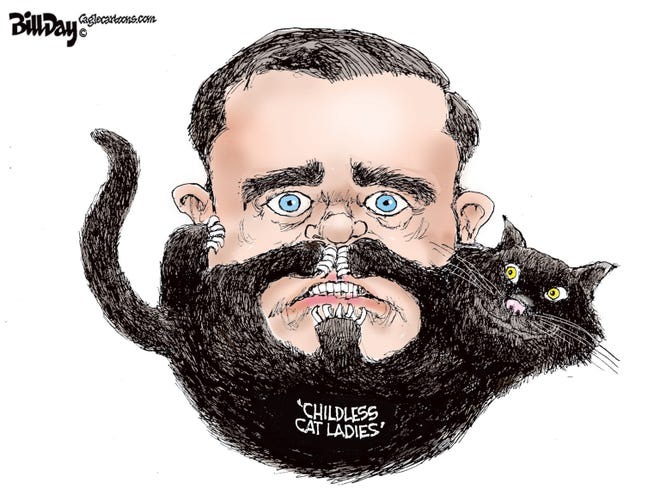

The man who may very well become the vice-president of the US once told Fox News that the country is governed by a dastardly deep state comprised of cat lovers. His exact words from the 2021 interview with then Fox News host Tucker Carlson:

The man who may very well become the vice-president of the US once told Fox News that the country is governed by a dastardly deep state comprised of cat lovers. His exact words from the 2021 interview with then Fox News host Tucker Carlson:

We are effectively run in this country, via the Democrats, via our corporate oligarchs, by a bunch of childless cat ladies who are miserable at their own lives and the choices that they’ve made, and so they want to make the rest of the country miserable, too. And it’s just a basic fact if you look at Kamala Harris, Pete Buttigieg, AOC – the entire future of the Democrats is controlled by people without children. And how does it make any sense that we’ve turned our country over to people who don’t really have a direct stake in it.”

…To be honest, I doubt that Vance really believes that “childless cat ladies” run the US. I also don’t know if he really believes that you only have a stake in the future if you procreate. Vance, after all, is a man who doesn’t really seem to believe anything. As has been much discussed, this is a guy who once called Donald Trump “America’s Hitler” and who now has no problem standing shoulder to shoulder with him.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Albert Li in Science:

It sounded like the right thing to do. I was a first-year Ph.D. student in educational psychology, and my research adviser told me I should consider practicing open science—“being open and above board,” as he put it. He suggested I make my first-year research project a preregistered report. We would publish our planned methods and analysis in advance, an approach meant to minimize questionable research practices such as cherry-picking of results. I found myself at a crossroads. On one hand, the promise of enhancing transparency and reproducibility was compelling. On the other, I was frightened about potential negative repercussions.

It sounded like the right thing to do. I was a first-year Ph.D. student in educational psychology, and my research adviser told me I should consider practicing open science—“being open and above board,” as he put it. He suggested I make my first-year research project a preregistered report. We would publish our planned methods and analysis in advance, an approach meant to minimize questionable research practices such as cherry-picking of results. I found myself at a crossroads. On one hand, the promise of enhancing transparency and reproducibility was compelling. On the other, I was frightened about potential negative repercussions.

An ethos of secrecy had colored my academic training up to that point. When I was an undergraduate student in China, a respected mentor cautioned, “Do not rush to publish your data in preprints, as others might scoop your ideas. Do not share your code, as it invites scrutiny and criticism. And try not to share your raw data—it makes us vulnerable.” He insisted that nothing leave the lab—not data sets, code, methodologies, or even the challenges we encountered. In papers we published, I wrote that the data remained confidential or was only available upon reasonable request, knowing that we would often opt not to share. The arrangement made me feel a bit uneasy, but I mostly accepted it as the way things had to be done to protect against intellectual theft.

But when I moved to the United States to pursue my Ph.D., the value of open science began to grow increasingly clear.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Alec Wilkinson at the NYT:

In “The Secret Lives of Numbers,” Kate Kitagawa, a mathematics historian, and Timothy Revell, a science writer, intend by reasoned and scholarly means to overthrow the “assumption that the European way of doing things is superior.”

In “The Secret Lives of Numbers,” Kate Kitagawa, a mathematics historian, and Timothy Revell, a science writer, intend by reasoned and scholarly means to overthrow the “assumption that the European way of doing things is superior.”

Their book begins with prehistoric counting methods (one of the earliest was based on the number 60, unlike our own base-10 system) and goes on to the fourth-century Alexandrian women Pandrosion, a geometer who solved the difficult problem of doubling the volume of a cube (ancient mathematicians lacked the algebra that makes this straightforward), and Hypatia, who wrote mathematical commentaries, including on Apollonius’ “Conics,” an investigation of circles, ellipses and other shapes. Kitagawa and Revell speculate that Johannes Kepler, who described the orbits of the planets in the 17th century, may have been influenced by her contributions.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Fire shimmied and reached up

From the iron furnace and grabbed

Sawdust from the pitchfork

Before I could make it across

The floor or take a half step

Back, as the boiler room sung

About what trees were before

Men & money. Those nights

Smelled of greenness & sweat

As steam moved through miles

Of winding pipes to turn wheels

That pushed blades and rotated

Man-high saws. It leaped

Like tigers out of a pit,

Singeing the hair on my head,

While Daddy made his rounds

Turning large brass keys

In his night-watchman’s clock,

Out among columns of lumber & paths

Where a man and woman might meet.

I daydreamed some freighter

Across a midnight ocean,

Leaving Taipei & headed

For Tripoli. I saw myself fall

Through a tumbling inferno

As if hell was where a boy

Shoveled clouds of sawdust

Into the wide mouth of doubt.

by Yusef Komunyakaa

from New American Poets of the ’90s

David R. Godine, publisher, 1991

John Simpson in The Guardian:

Anne Applebaum, as anyone familiar with her writing will know, is well-positioned to catalogue this new age of autocracy. Like her, Autocracy, Inc. is clear-sighted and fearless. I remember disagreeing with her genteelly at editorial meetings in the early 1990s, when she was writing about the danger that Russia’s post-communist implosion would one day present for the west, after Boris Yeltsin left office. She talked even then about the need for Nato to build up its defences against the time when Russia would be resurgent; while I, having spent so much time in the economic devastation of Moscow and St Petersburg, thought the best way for the west to protect itself was by being far more generous and welcoming towards Russia. Events have shown which of us was right, and it wasn’t me.

Anne Applebaum, as anyone familiar with her writing will know, is well-positioned to catalogue this new age of autocracy. Like her, Autocracy, Inc. is clear-sighted and fearless. I remember disagreeing with her genteelly at editorial meetings in the early 1990s, when she was writing about the danger that Russia’s post-communist implosion would one day present for the west, after Boris Yeltsin left office. She talked even then about the need for Nato to build up its defences against the time when Russia would be resurgent; while I, having spent so much time in the economic devastation of Moscow and St Petersburg, thought the best way for the west to protect itself was by being far more generous and welcoming towards Russia. Events have shown which of us was right, and it wasn’t me.

Autocracy, Inc. is deeply disturbing; it couldn’t be anything else. But Applebaum’s research is as always thoroughgoing, which makes it a lively pleasure to read.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

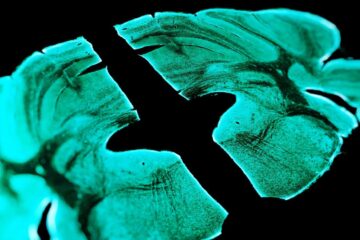

Grace Wade in New Scientist:

A newly identified brain pathway in mice could explain why placebos, or interventions designed to have no therapeutic effect, still relieve pain. Developing drugs that target this pathway may lead to safer alternatives to pain medications like opioids.

A newly identified brain pathway in mice could explain why placebos, or interventions designed to have no therapeutic effect, still relieve pain. Developing drugs that target this pathway may lead to safer alternatives to pain medications like opioids.

If someone unknowingly takes a sugar pill instead of a pain reliever, they still feel better. This placebo effect is a well-known phenomenon in which people’s expectations lessen their symptoms, even without effective treatment. “Our brain, on its own, is sort of able to fix the pain problem based on the expectation that a medication or treatment might work,” says Grégory Scherrer at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

To understand how the brain does this, Scherrer and his colleagues replicated the placebo effect in 10 mice using a cage with two chambers. One chamber had a burning hot floor, while the other didn’t. After three days, the animals learned to associate the second chamber with pain relief.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Yascha Mounk at his own Substack:

Once upon a time, Henderson argues, the upper classes used to signal their status by purchasing expensive material goods. But as the kinds of goods that used to be reserved for members of the upper classes have become available to a much wider stratum of society, the affluent and highly educated have resorted to different status symbols to signal their superior standing. This is why luxury beliefs—jargon-heavy political slogans calling for positions that are widely unpopular among the general population—have substituted for luxury goods.

Once upon a time, Henderson argues, the upper classes used to signal their status by purchasing expensive material goods. But as the kinds of goods that used to be reserved for members of the upper classes have become available to a much wider stratum of society, the affluent and highly educated have resorted to different status symbols to signal their superior standing. This is why luxury beliefs—jargon-heavy political slogans calling for positions that are widely unpopular among the general population—have substituted for luxury goods.

The concept of luxury beliefs achieved a feat shared by few neologisms: it entered “the discourse.” It is now frequently invoked on social media. It has been used in a key speech by a British Home Secretary. It has its own Wikipedia page.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.