Paul Cooper at Literary Hub:

One Sumerian epic poem called Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta gives the first known story about the invention of writing, by a king who has to send so many messages that his messenger can’t remember them all.

One Sumerian epic poem called Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta gives the first known story about the invention of writing, by a king who has to send so many messages that his messenger can’t remember them all.

His speech was substantial, and its contents extensive… Because the messenger, whose mouth was tired, was not able to repeat it, the lord of Kulaba patted some clay and wrote the message as if on a tablet. Formerly, the writing of messages on clay was not established. Now, under that sun and on that day, it was indeed so.

The Sumerians had two things in virtually limitless abundance: the clay beneath their feet, and the reeds that grew on the marshes and riverbanks—and these combined to create the written word. They made marks on palm-sized tablets of wet clay with the ends of cut reeds, and the distinctive shape of these impressions gives this form of writing its name, from the Latin for “wedge-shaped”: cuneiform. The oldest cuneiform clay tablets come from the Sumerian city of Uruk, and date to the late fourth millennium BCE. They are ergonomically shaped to the human and, and as a result are roughly the dimensions of a modern smartphone.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Today, researchers are looking toward building quantum computers and ways to securely transfer information using an entirely new sister field called

Today, researchers are looking toward building quantum computers and ways to securely transfer information using an entirely new sister field called  I first came to the United States for an academic exchange at Columbia University in 2005, and have spent the bulk of my time here since starting my PhD at Harvard University in 2007. No country changes nature overnight, and America still retains many of the virtues with which I fell in love all those years ago. But there are days when I fear that the place has been transformed so deeply that the qualities that would once have been touted as quintessentially American have forever been lost.

I first came to the United States for an academic exchange at Columbia University in 2005, and have spent the bulk of my time here since starting my PhD at Harvard University in 2007. No country changes nature overnight, and America still retains many of the virtues with which I fell in love all those years ago. But there are days when I fear that the place has been transformed so deeply that the qualities that would once have been touted as quintessentially American have forever been lost. SHORTLY AFTER Alice Munro died, a line from the title story of her 2009 collection Too Much Happiness began circulating on the internet: “Always remember that when a man goes out of the room, he leaves everything in it behind […] When a woman goes out she carries everything that happened in the room along with her.” The quote appeared in white font over a black background. The only attribution was to Munro, so at the time, I assumed it was something she had said in an interview. It felt piercingly ironic that the female winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature was being remembered for a remark she made about women’s supposed inability to live outside the context of men. Then, I learned the line was delivered by a character in “Too Much Happiness,” Munro’s fictional account of a real 19th-century woman, Sofya Kovalevskaya. Shortly afterward, the world learned of the sexual abuse Munro’s youngest daughter, Andrea Skinner, experienced as a child from her stepfather, Munro’s second husband. An abuse that Munro herself had learned of decades ago and chose to ignore.

SHORTLY AFTER Alice Munro died, a line from the title story of her 2009 collection Too Much Happiness began circulating on the internet: “Always remember that when a man goes out of the room, he leaves everything in it behind […] When a woman goes out she carries everything that happened in the room along with her.” The quote appeared in white font over a black background. The only attribution was to Munro, so at the time, I assumed it was something she had said in an interview. It felt piercingly ironic that the female winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature was being remembered for a remark she made about women’s supposed inability to live outside the context of men. Then, I learned the line was delivered by a character in “Too Much Happiness,” Munro’s fictional account of a real 19th-century woman, Sofya Kovalevskaya. Shortly afterward, the world learned of the sexual abuse Munro’s youngest daughter, Andrea Skinner, experienced as a child from her stepfather, Munro’s second husband. An abuse that Munro herself had learned of decades ago and chose to ignore. The medals keep coming for US swimmers at the

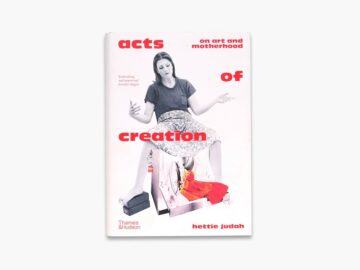

The medals keep coming for US swimmers at the  This remarkable book begins dramatically and truthfully: ‘A monstrous child is blocking my view and has carved a nest in the soft darkness of my head. It eats the hours, this child, leaving me only crumbs.’ Motherhood can be overwhelming, however longed for. It is never a small thing, even if the rest of the world chooses to ignore it or view it as a block to professionalism. Cyril Connolly’s remark in Enemies of Promise (1938), ‘There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall’, was, of course, a reference to male creativity. But women have routinely been brainwashed into concurring with this dismissive observation – made, admittedly, before Connolly had children. In the 1950s, respected male tutors in colleges of art would dismiss female making as ‘frustrated maternity’. The sculptor Reg Butler asked Slade School of Fine Art students in 1962, ‘Can a woman become a vital creative artist without ceasing to be a woman except for the purposes of a census?’

This remarkable book begins dramatically and truthfully: ‘A monstrous child is blocking my view and has carved a nest in the soft darkness of my head. It eats the hours, this child, leaving me only crumbs.’ Motherhood can be overwhelming, however longed for. It is never a small thing, even if the rest of the world chooses to ignore it or view it as a block to professionalism. Cyril Connolly’s remark in Enemies of Promise (1938), ‘There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall’, was, of course, a reference to male creativity. But women have routinely been brainwashed into concurring with this dismissive observation – made, admittedly, before Connolly had children. In the 1950s, respected male tutors in colleges of art would dismiss female making as ‘frustrated maternity’. The sculptor Reg Butler asked Slade School of Fine Art students in 1962, ‘Can a woman become a vital creative artist without ceasing to be a woman except for the purposes of a census?’ Fifty years ago, a young woman was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army, a ragtag group of revolutionaries willing to kill for gentle causes. For weeks, she recorded strident, sarcastic messages at her captors’ bidding, messages that bewildered and disturbed their intended audience. In time, she was taught the group’s thinking, given a nom de guerre (Tania), and handed a sawed-off carbine. She waved it around to help the SLA rob a bank—and later sprayed bullets from a machine gun to help them escape arrest. Of her own volition, she hid out with them for nearly a year. Public response swung from warm concern to fury.

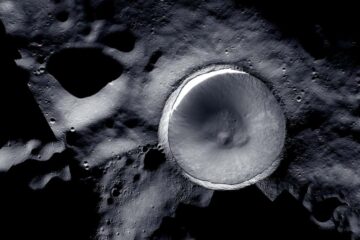

Fifty years ago, a young woman was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army, a ragtag group of revolutionaries willing to kill for gentle causes. For weeks, she recorded strident, sarcastic messages at her captors’ bidding, messages that bewildered and disturbed their intended audience. In time, she was taught the group’s thinking, given a nom de guerre (Tania), and handed a sawed-off carbine. She waved it around to help the SLA rob a bank—and later sprayed bullets from a machine gun to help them escape arrest. Of her own volition, she hid out with them for nearly a year. Public response swung from warm concern to fury. A backup of life on Earth could be kept safe in a permanently dark location on the moon, without the need for power or maintenance, allowing us to potentially restore organisms if they die out.

A backup of life on Earth could be kept safe in a permanently dark location on the moon, without the need for power or maintenance, allowing us to potentially restore organisms if they die out. Traditionally, Donald Trump has been

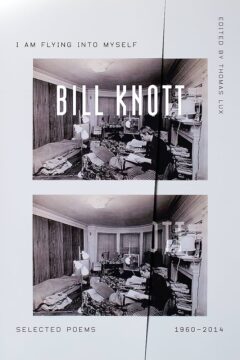

Traditionally, Donald Trump has been  While Knott may have alienated his peers in what

While Knott may have alienated his peers in what  David Keith was a graduate student in 1991 when a volcano erupted in the Philippines, sending a cloud of ash toward the edge of space. Seventeen million tons of sulfur dioxide released from Mount Pinatubo spread across the stratosphere, reflecting some of the sun’s energy away from Earth. The result was a drop in average temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere by roughly one degree Fahrenheit in the year that followed. Today, Dr. Keith cites that event as validation of an idea that has become his life’s work: He believes that by intentionally releasing sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere, it would be possible to lower temperatures worldwide, blunting global warming.

David Keith was a graduate student in 1991 when a volcano erupted in the Philippines, sending a cloud of ash toward the edge of space. Seventeen million tons of sulfur dioxide released from Mount Pinatubo spread across the stratosphere, reflecting some of the sun’s energy away from Earth. The result was a drop in average temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere by roughly one degree Fahrenheit in the year that followed. Today, Dr. Keith cites that event as validation of an idea that has become his life’s work: He believes that by intentionally releasing sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere, it would be possible to lower temperatures worldwide, blunting global warming. Baldwin Hills juts up 500 feet from the flat expanse of the Los Angeles Basin, the result of millennia of seismic activity along the Newport-Inglewood Fault, a dextral strike-slip fault that runs for 47 miles from Culver City through Signal Hill to Newport Beach. The fault, formed some 30 million years ago when the Pacific plate collided with the North American plate (an intersection that now sits at the San Andreas Fault), expresses on the surface as a series of low, irregular hills. Below the surface, seismic activity created a series of oil and gas reservoirs, including the Inglewood Oil Field.

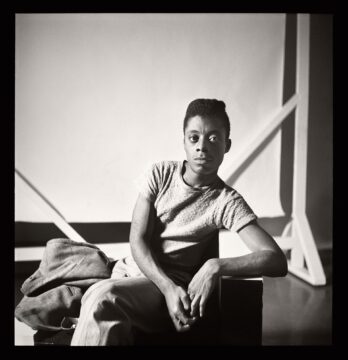

Baldwin Hills juts up 500 feet from the flat expanse of the Los Angeles Basin, the result of millennia of seismic activity along the Newport-Inglewood Fault, a dextral strike-slip fault that runs for 47 miles from Culver City through Signal Hill to Newport Beach. The fault, formed some 30 million years ago when the Pacific plate collided with the North American plate (an intersection that now sits at the San Andreas Fault), expresses on the surface as a series of low, irregular hills. Below the surface, seismic activity created a series of oil and gas reservoirs, including the Inglewood Oil Field. I underwent, during the summer that I became fourteen, a prolonged religious crisis. I use “religious” in the common, and arbitrary, sense, meaning that I then discovered God, His saints and angels, and His blazing Hell. And since I had been born in a Christian nation, I accepted this Deity as the only one. I supposed Him to exist only within the walls of a church—in fact, of our church—and I also supposed that God and safety were synonymous. The word “safety” brings us to the real meaning of the word “religious” as we use it. Therefore, to state it in another, more accurate way, I became, during my fourteenth year, for the first time in my life, afraid—afraid of the evil within me and afraid of the evil without. What I saw around me that summer in Harlem was what I had always seen; nothing had changed. But now, without any warning, the whores and pimps and racketeers on the Avenue had become a personal menace. It had not before occurred to me that I could become one of them, but now I realized that we had been produced by the same circumstances. Many of my comrades were clearly headed for the Avenue, and my father said that I was headed that way, too. My friends began to drink and smoke, and embarked—at first avid, then groaning—on their sexual careers. Girls, only slightly older than I was, who sang in the choir or taught Sunday school, the children of holy parents, underwent, before my eyes, their incredible metamorphosis, of which the most bewildering aspect was not their budding breasts or their rounding behinds but something deeper and more subtle, in their eyes, their heat, their odor, and the inflection of their voices.

I underwent, during the summer that I became fourteen, a prolonged religious crisis. I use “religious” in the common, and arbitrary, sense, meaning that I then discovered God, His saints and angels, and His blazing Hell. And since I had been born in a Christian nation, I accepted this Deity as the only one. I supposed Him to exist only within the walls of a church—in fact, of our church—and I also supposed that God and safety were synonymous. The word “safety” brings us to the real meaning of the word “religious” as we use it. Therefore, to state it in another, more accurate way, I became, during my fourteenth year, for the first time in my life, afraid—afraid of the evil within me and afraid of the evil without. What I saw around me that summer in Harlem was what I had always seen; nothing had changed. But now, without any warning, the whores and pimps and racketeers on the Avenue had become a personal menace. It had not before occurred to me that I could become one of them, but now I realized that we had been produced by the same circumstances. Many of my comrades were clearly headed for the Avenue, and my father said that I was headed that way, too. My friends began to drink and smoke, and embarked—at first avid, then groaning—on their sexual careers. Girls, only slightly older than I was, who sang in the choir or taught Sunday school, the children of holy parents, underwent, before my eyes, their incredible metamorphosis, of which the most bewildering aspect was not their budding breasts or their rounding behinds but something deeper and more subtle, in their eyes, their heat, their odor, and the inflection of their voices.