From Project Syndicate:

Project Syndicate: A year and a half ago, you criticized the US Federal Reserve’s response to inflation in the United States, arguing that, if anything, “disinflation has happened despite central banks’ actions, not because of them.” Now, many observers are highlighting the inflation risks of second Donald Trump administration, which would likely double down on import tariffs and seek a weaker dollar. Do you see other inflation risks on the horizon, and what should US policymakers be doing now to support continued price stability?

Joseph E. Stiglitz: There are four additional inflation risks associated with another Trump administration. The first is a tightening of immigration rules: as the US population ages, the labor force shrinks – a trend that, in the context of a tight labor market, will put further upward pressure on wages. Second, a second Trump administration would likely exercise little fiscal discipline – implementing, for example, unfunded tax cuts for corporations and billionaires; this could raise inflationary expectations and possibly even lead to an excess of aggregate demand. Third, a Trump administration would almost certainly abandon Joe Biden’s anti-monopoly policy, effectively giving corporations free reign to increase prices. Lastly, Trump’s likely interference with the US Federal Reserve might spook the markets, again leading to higher inflationary expectations.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

W

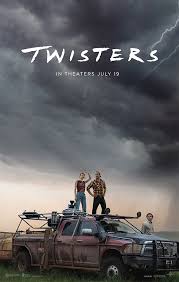

W Twisters, with a budget estimated at $200 million, is that enduring Hollywood paradox: the blockbuster that uses capitalism as shorthand for moral corruption. We know from the start that Javi’s business is compromised just by seeing its natty corporate graphics. (It would be interesting to know the costs for the logoed Twisters T-shirts worn by the ushers at the London premiere.)

Twisters, with a budget estimated at $200 million, is that enduring Hollywood paradox: the blockbuster that uses capitalism as shorthand for moral corruption. We know from the start that Javi’s business is compromised just by seeing its natty corporate graphics. (It would be interesting to know the costs for the logoed Twisters T-shirts worn by the ushers at the London premiere.) E

E Each night, as the line that separates day from night sweeps across the face of the ocean, a vast wave of life rises from the ocean’s depths behind it. Made up of an astonishing diversity of animals—myriad species of minute zooplankton, jellyfish and krill, savage squid and a confusion of fish species ranging from lanternfish to viperfish and eels, as well as stranger creatures such as translucent larvaceans and snotlike salps—this world-spanning tide travels surfaceward to feed in the safety of the dark, before retreating to the depths again at dawn.

Each night, as the line that separates day from night sweeps across the face of the ocean, a vast wave of life rises from the ocean’s depths behind it. Made up of an astonishing diversity of animals—myriad species of minute zooplankton, jellyfish and krill, savage squid and a confusion of fish species ranging from lanternfish to viperfish and eels, as well as stranger creatures such as translucent larvaceans and snotlike salps—this world-spanning tide travels surfaceward to feed in the safety of the dark, before retreating to the depths again at dawn. F

F ALARMINGLY,

ALARMINGLY, Picturing the Mind

Picturing the Mind