Rahul Bhatia in The Guardian:

Running a finger over a row of books in a Delhi library one afternoon, I stopped at a title that promised danger. The stacks were abundant in books like RSS Misunderstood and Is RSS the Enemy?, which often turned out to be self-published polemics that were too long, however short they were. This one was different. On its front was the full title, In the Belly of the Beast: The Hindu Supremacist RSS and the BJP of India, An Insider’s View. I read the first page, and then the next, slowly, with rising giddiness. Not long after, I was beside a Sikh gentleman at his photocopying machine. What pages, he asked. Everything, I said.

Running a finger over a row of books in a Delhi library one afternoon, I stopped at a title that promised danger. The stacks were abundant in books like RSS Misunderstood and Is RSS the Enemy?, which often turned out to be self-published polemics that were too long, however short they were. This one was different. On its front was the full title, In the Belly of the Beast: The Hindu Supremacist RSS and the BJP of India, An Insider’s View. I read the first page, and then the next, slowly, with rising giddiness. Not long after, I was beside a Sikh gentleman at his photocopying machine. What pages, he asked. Everything, I said.

In the long hour that followed, I wondered if the book’s presence on these shelves was an oversight. This was the closest that any writer had come to describing the organisation from within. That night I swallowed its contents whole, scanned a copy for myself to store in several places for safekeeping, and wrote to its author. We mailed, and then scheduled a video call, and then arranged to meet two months later, when he travelled to India from the US to alert people to the dangers of the RSS before the 2024 elections began.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Hundreds of millions of people across the globe now earn their living less with their backs and more with their brains, relying on sharp reasoning and creative thinking. So how about seeing who’s best at that?

Hundreds of millions of people across the globe now earn their living less with their backs and more with their brains, relying on sharp reasoning and creative thinking. So how about seeing who’s best at that? W

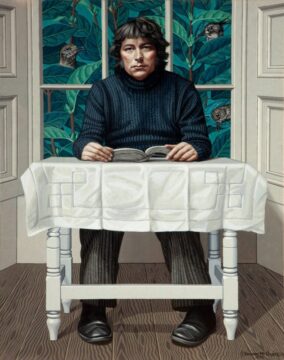

W OPEN ANY BOOK BY CAROLINE BLACKWOOD and you will encounter the same woman. Articulate, adrift, callous, cosmically self-absorbed. She’s in the middle of her life, a retired actress or model, once striking and sought-after. Her misery has a predatory quality. Decisions made idly and capriciously she now clings to as essential facets of her “character.” She rebels continually against the restraints and privations she inflicts upon herself. She behaves as though she were onstage, thundering dramatic monologues of deceit and self-justification. What’s clearest is her anger: pure, whole, just beneath the surface, like a calcium deposit under the skin.

OPEN ANY BOOK BY CAROLINE BLACKWOOD and you will encounter the same woman. Articulate, adrift, callous, cosmically self-absorbed. She’s in the middle of her life, a retired actress or model, once striking and sought-after. Her misery has a predatory quality. Decisions made idly and capriciously she now clings to as essential facets of her “character.” She rebels continually against the restraints and privations she inflicts upon herself. She behaves as though she were onstage, thundering dramatic monologues of deceit and self-justification. What’s clearest is her anger: pure, whole, just beneath the surface, like a calcium deposit under the skin. At the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden, Jim Thorpe easily won the decathlon in the first modern version of the event. The grueling, ten-part feat was not the only addition to the burgeoning modern games. Other events that debuted at the 1912 Olympics included architecture, sculpture, painting, music… and literature.

At the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden, Jim Thorpe easily won the decathlon in the first modern version of the event. The grueling, ten-part feat was not the only addition to the burgeoning modern games. Other events that debuted at the 1912 Olympics included architecture, sculpture, painting, music… and literature. Drivers on a busy US freeway have been controlled by an AI since March, as part of a study that has put a machine-learning system in charge of setting variable speed limits on the road. The impact on efficiency and driver safety is unclear, as researchers are still analysing the results.

Drivers on a busy US freeway have been controlled by an AI since March, as part of a study that has put a machine-learning system in charge of setting variable speed limits on the road. The impact on efficiency and driver safety is unclear, as researchers are still analysing the results. Transnational organized crime is a paradox: ubiquitous yet invisible. While criminal tactics evolve rapidly, government-led responses are often static. When criminal networks are squeezed in one jurisdiction, they rapidly balloon in another. Although the problem concerns everyone, it is often considered too sensitive to discuss at the national, much less the global, level. As a result, the international community – including the United Nations and its member states –

Transnational organized crime is a paradox: ubiquitous yet invisible. While criminal tactics evolve rapidly, government-led responses are often static. When criminal networks are squeezed in one jurisdiction, they rapidly balloon in another. Although the problem concerns everyone, it is often considered too sensitive to discuss at the national, much less the global, level. As a result, the international community – including the United Nations and its member states –  My family history of cancer is impressive, and not in a good way.

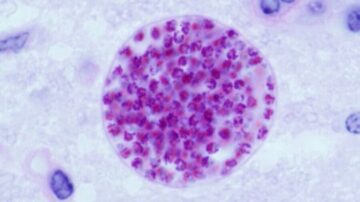

My family history of cancer is impressive, and not in a good way. The brain is like a medieval castle perched on a cliff, protected on all sides by high walls, making it nearly impenetrable. Its shield is the blood-brain barrier, a layer of tightly connected cells that only allows an extremely selective group of molecules to pass. The barrier keeps delicate brain cells safely away from harmful substances, but it also blocks therapeutic proteins—like, for example, those that grab onto and neutralize toxic clumps in Alzheimer’s disease. One way to smuggle proteins across? A cat parasite. A

The brain is like a medieval castle perched on a cliff, protected on all sides by high walls, making it nearly impenetrable. Its shield is the blood-brain barrier, a layer of tightly connected cells that only allows an extremely selective group of molecules to pass. The barrier keeps delicate brain cells safely away from harmful substances, but it also blocks therapeutic proteins—like, for example, those that grab onto and neutralize toxic clumps in Alzheimer’s disease. One way to smuggle proteins across? A cat parasite. A  Freud’s influence waned during the 1980s and 1990s, in part because of the so-called “Freud Wars,” during which critics like

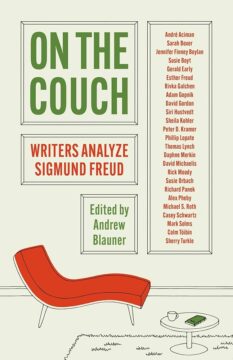

Freud’s influence waned during the 1980s and 1990s, in part because of the so-called “Freud Wars,” during which critics like

This buoyant anvil of a book has brought me to the edge of a nervous breakdown. Night after night I’m waking with Seamus Heaney sizzling through—not me, exactly, but the me I was thirty-four years ago when I first read him, in a one-windowed, mold-walled studio in Seattle, when night after night I woke with another current (is it another current?) sizzling through my circuits: ambition. Not ambition to succeed on the world’s terms (though that asserted its own maddening static) but ambition to find forms for the seethe of rage, remembrance, and wild vitality that seemed, unaccountably, like sound inside me, demanding language but prelinguistic, somehow. I felt imprisoned by these vague but stabbing haunt-songs that were, I sensed, my only means of freedom.

This buoyant anvil of a book has brought me to the edge of a nervous breakdown. Night after night I’m waking with Seamus Heaney sizzling through—not me, exactly, but the me I was thirty-four years ago when I first read him, in a one-windowed, mold-walled studio in Seattle, when night after night I woke with another current (is it another current?) sizzling through my circuits: ambition. Not ambition to succeed on the world’s terms (though that asserted its own maddening static) but ambition to find forms for the seethe of rage, remembrance, and wild vitality that seemed, unaccountably, like sound inside me, demanding language but prelinguistic, somehow. I felt imprisoned by these vague but stabbing haunt-songs that were, I sensed, my only means of freedom.