Corey Robin in The New Yorker:

My first and only experience of antisemitism in America came wrapped in a bow of care and concern. In 1993, I spent the summer in Tennessee with my girlfriend. At a barbecue, we were peppered with questions. What brought us south? How were we getting on? Where did we go to church? We explained that we didn’t go to church because we were Jewish. “That’s O.K.,” a woman reassured us. Having never thought that it wasn’t, I flashed a puzzled smile and recalled an observation of the German writer Ludwig Börne: “Some reproach me with being a Jew, others pardon me, still others praise me for it. But all are thinking about it.”

Thirty-one years later, everyone’s thinking about the Jews. Poll after poll asks them if they feel safe. Donald Trump and Kamala Harris lob insults about who’s the greater antisemite. Congressional Republicans, who have all of two Jews in their caucus, deliver lectures on Jewish history to university leaders. “I want you to kneel down and touch the stone which paved the grounds of Auschwitz,” the Oregon Republican Lori Chavez-DeRemer declared at a hearing in May, urging a visit to D.C.’s Holocaust museum. “I want you to peer over the countless shoes of murdered Jews.” She gave no indication of knowing that one of the leaders she was addressing had been a victim of antisemitism or that another was the descendant of Holocaust survivors.

It’s no accident that non-Jews talk about Jews as if we aren’t there. According to the historian David Nirenberg, talking about the Jews—not actual Jews but Jews in the abstract—is how Gentiles make sense of their world, from the largest questions of existence to the smallest questions of economics.

More here,

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

This buoyant anvil of a book has brought me to the edge of a nervous breakdown. Night after night I’m waking with Seamus Heaney sizzling through—not me, exactly, but the me I was thirty-four years ago when I first read him, in a one-windowed, mold-walled studio in Seattle, when night after night I woke with another current (is it another current?) sizzling through my circuits: ambition. Not ambition to succeed on the world’s terms (though that asserted its own maddening static) but ambition to find forms for the seethe of rage, remembrance, and wild vitality that seemed, unaccountably, like sound inside me, demanding language but prelinguistic, somehow. I felt imprisoned by these vague but stabbing haunt-songs that were, I sensed, my only means of freedom.

This buoyant anvil of a book has brought me to the edge of a nervous breakdown. Night after night I’m waking with Seamus Heaney sizzling through—not me, exactly, but the me I was thirty-four years ago when I first read him, in a one-windowed, mold-walled studio in Seattle, when night after night I woke with another current (is it another current?) sizzling through my circuits: ambition. Not ambition to succeed on the world’s terms (though that asserted its own maddening static) but ambition to find forms for the seethe of rage, remembrance, and wild vitality that seemed, unaccountably, like sound inside me, demanding language but prelinguistic, somehow. I felt imprisoned by these vague but stabbing haunt-songs that were, I sensed, my only means of freedom. One Sumerian epic poem called Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta gives the first known story about the invention of writing, by a king who has to send so many messages that his messenger can’t remember them all.

One Sumerian epic poem called Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta gives the first known story about the invention of writing, by a king who has to send so many messages that his messenger can’t remember them all. Today, researchers are looking toward building quantum computers and ways to securely transfer information using an entirely new sister field called

Today, researchers are looking toward building quantum computers and ways to securely transfer information using an entirely new sister field called  I first came to the United States for an academic exchange at Columbia University in 2005, and have spent the bulk of my time here since starting my PhD at Harvard University in 2007. No country changes nature overnight, and America still retains many of the virtues with which I fell in love all those years ago. But there are days when I fear that the place has been transformed so deeply that the qualities that would once have been touted as quintessentially American have forever been lost.

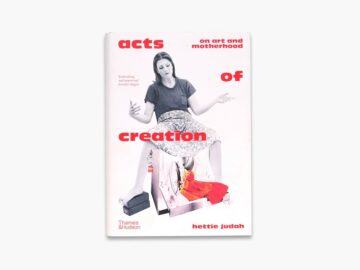

I first came to the United States for an academic exchange at Columbia University in 2005, and have spent the bulk of my time here since starting my PhD at Harvard University in 2007. No country changes nature overnight, and America still retains many of the virtues with which I fell in love all those years ago. But there are days when I fear that the place has been transformed so deeply that the qualities that would once have been touted as quintessentially American have forever been lost. SHORTLY AFTER Alice Munro died, a line from the title story of her 2009 collection Too Much Happiness began circulating on the internet: “Always remember that when a man goes out of the room, he leaves everything in it behind […] When a woman goes out she carries everything that happened in the room along with her.” The quote appeared in white font over a black background. The only attribution was to Munro, so at the time, I assumed it was something she had said in an interview. It felt piercingly ironic that the female winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature was being remembered for a remark she made about women’s supposed inability to live outside the context of men. Then, I learned the line was delivered by a character in “Too Much Happiness,” Munro’s fictional account of a real 19th-century woman, Sofya Kovalevskaya. Shortly afterward, the world learned of the sexual abuse Munro’s youngest daughter, Andrea Skinner, experienced as a child from her stepfather, Munro’s second husband. An abuse that Munro herself had learned of decades ago and chose to ignore.

SHORTLY AFTER Alice Munro died, a line from the title story of her 2009 collection Too Much Happiness began circulating on the internet: “Always remember that when a man goes out of the room, he leaves everything in it behind […] When a woman goes out she carries everything that happened in the room along with her.” The quote appeared in white font over a black background. The only attribution was to Munro, so at the time, I assumed it was something she had said in an interview. It felt piercingly ironic that the female winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature was being remembered for a remark she made about women’s supposed inability to live outside the context of men. Then, I learned the line was delivered by a character in “Too Much Happiness,” Munro’s fictional account of a real 19th-century woman, Sofya Kovalevskaya. Shortly afterward, the world learned of the sexual abuse Munro’s youngest daughter, Andrea Skinner, experienced as a child from her stepfather, Munro’s second husband. An abuse that Munro herself had learned of decades ago and chose to ignore. The medals keep coming for US swimmers at the

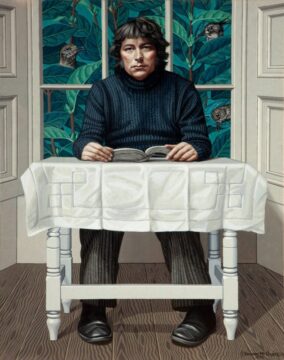

The medals keep coming for US swimmers at the  This remarkable book begins dramatically and truthfully: ‘A monstrous child is blocking my view and has carved a nest in the soft darkness of my head. It eats the hours, this child, leaving me only crumbs.’ Motherhood can be overwhelming, however longed for. It is never a small thing, even if the rest of the world chooses to ignore it or view it as a block to professionalism. Cyril Connolly’s remark in Enemies of Promise (1938), ‘There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall’, was, of course, a reference to male creativity. But women have routinely been brainwashed into concurring with this dismissive observation – made, admittedly, before Connolly had children. In the 1950s, respected male tutors in colleges of art would dismiss female making as ‘frustrated maternity’. The sculptor Reg Butler asked Slade School of Fine Art students in 1962, ‘Can a woman become a vital creative artist without ceasing to be a woman except for the purposes of a census?’

This remarkable book begins dramatically and truthfully: ‘A monstrous child is blocking my view and has carved a nest in the soft darkness of my head. It eats the hours, this child, leaving me only crumbs.’ Motherhood can be overwhelming, however longed for. It is never a small thing, even if the rest of the world chooses to ignore it or view it as a block to professionalism. Cyril Connolly’s remark in Enemies of Promise (1938), ‘There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall’, was, of course, a reference to male creativity. But women have routinely been brainwashed into concurring with this dismissive observation – made, admittedly, before Connolly had children. In the 1950s, respected male tutors in colleges of art would dismiss female making as ‘frustrated maternity’. The sculptor Reg Butler asked Slade School of Fine Art students in 1962, ‘Can a woman become a vital creative artist without ceasing to be a woman except for the purposes of a census?’ Fifty years ago, a young woman was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army, a ragtag group of revolutionaries willing to kill for gentle causes. For weeks, she recorded strident, sarcastic messages at her captors’ bidding, messages that bewildered and disturbed their intended audience. In time, she was taught the group’s thinking, given a nom de guerre (Tania), and handed a sawed-off carbine. She waved it around to help the SLA rob a bank—and later sprayed bullets from a machine gun to help them escape arrest. Of her own volition, she hid out with them for nearly a year. Public response swung from warm concern to fury.

Fifty years ago, a young woman was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army, a ragtag group of revolutionaries willing to kill for gentle causes. For weeks, she recorded strident, sarcastic messages at her captors’ bidding, messages that bewildered and disturbed their intended audience. In time, she was taught the group’s thinking, given a nom de guerre (Tania), and handed a sawed-off carbine. She waved it around to help the SLA rob a bank—and later sprayed bullets from a machine gun to help them escape arrest. Of her own volition, she hid out with them for nearly a year. Public response swung from warm concern to fury.