Patrick Warner in Literary Review of Canada:

Writers are those naïfs among us who believe that language can be used to take the measure of experience. Readers demonstrate faith in them when they commit to a book or short story. The reader-writer relationship is a contract of sorts. But because the terms are not written down, there is much room in that contract for misinterpretation. What is at stake is not small: it is a shared picture of reality. Nor is it static. With each new publication or rereading, the reader-writer contract is up for review. What could go wrong?

Writers are those naïfs among us who believe that language can be used to take the measure of experience. Readers demonstrate faith in them when they commit to a book or short story. The reader-writer relationship is a contract of sorts. But because the terms are not written down, there is much room in that contract for misinterpretation. What is at stake is not small: it is a shared picture of reality. Nor is it static. With each new publication or rereading, the reader-writer contract is up for review. What could go wrong?

In every closely examined work of creativity, no matter how successful, there is a frightening degree of illusion. Once, in an art gallery, I was taken with a work of Flemish realism depicting a man who wore the most dazzling lace collar. I moved closer and closer, until I could see that the fine textile was simply a series of crude white dots joined together by off-white and grey dashes. I walked backwards, away from the painting, while keeping my eyes fixed on it. Suddenly the lace collar miraculously and convincingly reappeared. For art lovers, such a thing is a marvel. For those looking for a simplified truth, it can be deeply distressing. Artifice is problematic for those who insist that all sleights of hand are meant to deceive, most likely for nefarious purposes. Is it any wonder that artists and writers in this age of mass media have looked to pull back the curtain on their practice?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

W

W I do not think that being mean is a virtue, but it is related to the virtue by means of which we tell the truth. There are other ways of telling the truth. We can be circumspect or ironic—there is very often a nicer way to put something. Yet there are good reasons for sometimes being just a little bit mean. (No, I am not thinking about that gratuitously nasty and rebarbative character now dominating our public realm.) I think of being mean the way that the King of Brobdingnag in Gulliver’s Travels talks about dangerous views: “For a man may be allowed to keep poisons in his closet, but not to vend them about for cordials.” That is to say, I think being nice is required for good politics, but being mean has definite social utility in private life—and it should stay there.

I do not think that being mean is a virtue, but it is related to the virtue by means of which we tell the truth. There are other ways of telling the truth. We can be circumspect or ironic—there is very often a nicer way to put something. Yet there are good reasons for sometimes being just a little bit mean. (No, I am not thinking about that gratuitously nasty and rebarbative character now dominating our public realm.) I think of being mean the way that the King of Brobdingnag in Gulliver’s Travels talks about dangerous views: “For a man may be allowed to keep poisons in his closet, but not to vend them about for cordials.” That is to say, I think being nice is required for good politics, but being mean has definite social utility in private life—and it should stay there. Robotic vehicles can

Robotic vehicles can  One of the core assumptions of modern liberalism is that if you can solve the problem of material scarcity, you can go a long way to solving the problem of free and peaceful coexistence among equals. Modern technology has been essential to that dynamic from the start, a key driver of “development” and the success of democratic regimes. The West, and large parts of the rest of the world, are what they are today in great measure due to this project.

One of the core assumptions of modern liberalism is that if you can solve the problem of material scarcity, you can go a long way to solving the problem of free and peaceful coexistence among equals. Modern technology has been essential to that dynamic from the start, a key driver of “development” and the success of democratic regimes. The West, and large parts of the rest of the world, are what they are today in great measure due to this project. A newly developed blood test for

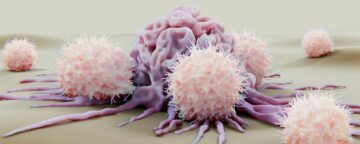

A newly developed blood test for  If you hear the word Ozempic, weight loss immediately comes to mind. The drug—part of a family of treatments called GLP-1 agonists—took the medical world (and internet) by storm for helping people manage diabetes, lower the risk of heart disease, and rapidly lose weight. The drugs may also protect the brain against dementia. In a clinical trial including over 200 people with mild Alzheimer’s disease, a daily injection of a GLP-1 drug for one year slowed cognitive decline. When challenged with a battery of tests assessing memory, language skills, and decision-making, participants who took the drug remained sharper for longer than those who took a placebo—an injection that looked the same but wasn’t functional. The results are the latest from the

If you hear the word Ozempic, weight loss immediately comes to mind. The drug—part of a family of treatments called GLP-1 agonists—took the medical world (and internet) by storm for helping people manage diabetes, lower the risk of heart disease, and rapidly lose weight. The drugs may also protect the brain against dementia. In a clinical trial including over 200 people with mild Alzheimer’s disease, a daily injection of a GLP-1 drug for one year slowed cognitive decline. When challenged with a battery of tests assessing memory, language skills, and decision-making, participants who took the drug remained sharper for longer than those who took a placebo—an injection that looked the same but wasn’t functional. The results are the latest from the  There’s no question that we love to talk — but how did it happen? Yes, humpback whales sing, vervet monkeys use alarm calls, and bees convey information about food sources through dance, but

There’s no question that we love to talk — but how did it happen? Yes, humpback whales sing, vervet monkeys use alarm calls, and bees convey information about food sources through dance, but  How many clinical-trial studies in medical journals are fake or fatally flawed? In October 2020, John Carlisle reported a startling estimate

How many clinical-trial studies in medical journals are fake or fatally flawed? In October 2020, John Carlisle reported a startling estimate Last month, the House of Representatives

Last month, the House of Representatives  Fact: The Windy City nickname has nothing to do with Chicago’s weather

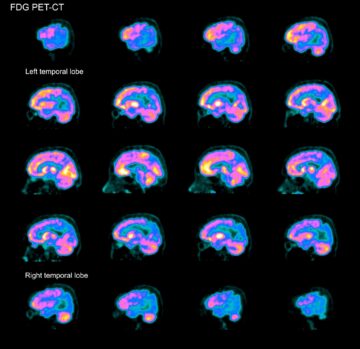

Fact: The Windy City nickname has nothing to do with Chicago’s weather Like many Alzheimer’s researchers, neurologist Randall Bateman is not prone to effusiveness, having endured disappointments in his field. But he and others have found one big reason to be excited lately. In just a few years, he predicts, there will be a simple blood test for your risk of Alzheimer’s. “Any family doctor will be able to do it.” Bateman, who is at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, has been running

Like many Alzheimer’s researchers, neurologist Randall Bateman is not prone to effusiveness, having endured disappointments in his field. But he and others have found one big reason to be excited lately. In just a few years, he predicts, there will be a simple blood test for your risk of Alzheimer’s. “Any family doctor will be able to do it.” Bateman, who is at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, has been running  It was once common, in Western societies at least, to think of plants as the passive, inert background to animal life, or as mere animal fodder. Plants could be fascinating in their own right, of course, but they lacked much of what made animals and humans interesting, such as agency, intelligence, cognition, intention, consciousness, decision-making, self-identification, sociality and altruism. However, groundbreaking developments in the plant sciences since the end of the previous century have blown that view out of the water. We are just beginning to glimpse the extraordinary complexity and subtlety of plants’ relations with their environment, with each other and with other living beings. We owe these radical developments in our understanding of plants to one area of study in particular: the study of plant behaviour.

It was once common, in Western societies at least, to think of plants as the passive, inert background to animal life, or as mere animal fodder. Plants could be fascinating in their own right, of course, but they lacked much of what made animals and humans interesting, such as agency, intelligence, cognition, intention, consciousness, decision-making, self-identification, sociality and altruism. However, groundbreaking developments in the plant sciences since the end of the previous century have blown that view out of the water. We are just beginning to glimpse the extraordinary complexity and subtlety of plants’ relations with their environment, with each other and with other living beings. We owe these radical developments in our understanding of plants to one area of study in particular: the study of plant behaviour. Many entrepreneurs have tried to create prediction markets, contracts that trade on the outcome of future events. Luke Nosek, cofounder of PayPal, once

Many entrepreneurs have tried to create prediction markets, contracts that trade on the outcome of future events. Luke Nosek, cofounder of PayPal, once  As someone trained in physics, and as an academic paid to research, I have been drawn to studying one essential contributor to these crises: how energy and electricity are produced, especially those methods proposed to mitigate climate change. Prominent among these proposals is nuclear energy.

As someone trained in physics, and as an academic paid to research, I have been drawn to studying one essential contributor to these crises: how energy and electricity are produced, especially those methods proposed to mitigate climate change. Prominent among these proposals is nuclear energy.