Sophia Chen in Nature:

The fastest supercomputer in the world is a machine known as Frontier, but even this speedster with nearly 50,000 processors has its limits. On a sunny Monday in April, its power consumption is spiking as it tries to keep up with the amount of work requested by scientific groups around the world. The electricity demand peaks at around 27 megawatts, enough to power roughly 10,000 houses, says Bronson Messer, director of science at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, where Frontier is located. With a note of pride in his voice, Messer uses a local term to describe the supercomputer’s work rate: “They are running the machine like a scalded dog.”

The fastest supercomputer in the world is a machine known as Frontier, but even this speedster with nearly 50,000 processors has its limits. On a sunny Monday in April, its power consumption is spiking as it tries to keep up with the amount of work requested by scientific groups around the world. The electricity demand peaks at around 27 megawatts, enough to power roughly 10,000 houses, says Bronson Messer, director of science at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, where Frontier is located. With a note of pride in his voice, Messer uses a local term to describe the supercomputer’s work rate: “They are running the machine like a scalded dog.”

Frontier churns through data at record speed, outpacing 100,000 laptops working simultaneously. When it debuted in 2022, it was the first to break through supercomputing’s exascale speed barrier — the capability of executing an exaflop, or 1018 floating point operations per second. The Oak Ridge behemoth is the latest chart-topper in a decades-long global trend of pushing towards larger supercomputers (although it is possible that faster computers exist in military labs or otherwise secret facilities).

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

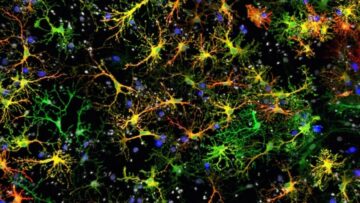

After a lull of nearly 2 decades, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved some novel drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease since 2021. Most of these drugs are antibody therapies targeting toxic protein aggregates in the brain. Their approval has sparked enthusiasm and controversy in equal measure. The core question remains: Are these drugs making a real difference? In this Special Feature, we investigate. Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease that involves a gradual and irreversible decline in memory, thinking, and, eventually, the ability to perform daily activities. Aging is the leading risk factor for

After a lull of nearly 2 decades, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved some novel drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease since 2021. Most of these drugs are antibody therapies targeting toxic protein aggregates in the brain. Their approval has sparked enthusiasm and controversy in equal measure. The core question remains: Are these drugs making a real difference? In this Special Feature, we investigate. Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease that involves a gradual and irreversible decline in memory, thinking, and, eventually, the ability to perform daily activities. Aging is the leading risk factor for  At some point in the early morning, having forfeited my grip on the laminate, I was squeezed onto a balcony between Klaus and a very tall Polish American man, who was telling us about an upcoming trip to Kerala, where he would seek ayurvedic realignment after a season of encounters with unmitigated evil in Berlin. A third figure in a stiff leather jacket produced a red packet of cigarettes and distributed them with gravity, as if they were full-bodied charms. Klaus asked a question. Did you know that American Spirit was founded by one of Kojève’s graduate students, who named the tobacco company after Hegelian Spirit or Geist? I did not. This is the same Alexandre Kojève who had been born into Russian aristocracy, fled to Berlin after the October Revolution (and after an arrest for black-marketing soap), financed his early life by selling off the family jewels, enshrined himself as a chief architect of the European Economic Community, spied for the Kremlin for decades (or so it has been posthumously conjectured, without thorough proof), and did more than any other philosopher to shape the reception of Hegel’s thought in twentieth-century Europe. He was also, it seems, fond of anecdote, and liked to recycle one in particular. It went something like… when Hegel was asked, during a lecture on the philosophy of history, about the spirit of America, he thought for a moment and then replied: tobacco!

At some point in the early morning, having forfeited my grip on the laminate, I was squeezed onto a balcony between Klaus and a very tall Polish American man, who was telling us about an upcoming trip to Kerala, where he would seek ayurvedic realignment after a season of encounters with unmitigated evil in Berlin. A third figure in a stiff leather jacket produced a red packet of cigarettes and distributed them with gravity, as if they were full-bodied charms. Klaus asked a question. Did you know that American Spirit was founded by one of Kojève’s graduate students, who named the tobacco company after Hegelian Spirit or Geist? I did not. This is the same Alexandre Kojève who had been born into Russian aristocracy, fled to Berlin after the October Revolution (and after an arrest for black-marketing soap), financed his early life by selling off the family jewels, enshrined himself as a chief architect of the European Economic Community, spied for the Kremlin for decades (or so it has been posthumously conjectured, without thorough proof), and did more than any other philosopher to shape the reception of Hegel’s thought in twentieth-century Europe. He was also, it seems, fond of anecdote, and liked to recycle one in particular. It went something like… when Hegel was asked, during a lecture on the philosophy of history, about the spirit of America, he thought for a moment and then replied: tobacco! This disinclination to reread the books I treasure alienates me not just from Nabokov, but from a vast pro-rereading discourse espoused by geniuses who regard rereading as the literary activity par excellence. Roland Barthes, for instance, proposed that rereading is necessary if we are to realize the true goal of literature, which, in his view, is to make the reader “no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text.” When we reread, we discover how a text can multiply in its variety and its plurality. Rereading offers something beyond a more detailed comprehension of the text: it is, Barthes claims, “an operation contrary to the commercial and ideological habits of our society, which would have us ‘throw away’ the story once it has been consumed (‘devoured’).” I’m not so sure.

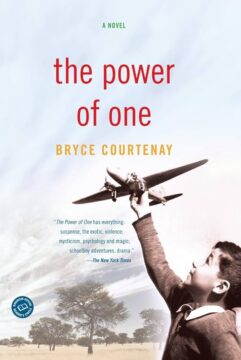

This disinclination to reread the books I treasure alienates me not just from Nabokov, but from a vast pro-rereading discourse espoused by geniuses who regard rereading as the literary activity par excellence. Roland Barthes, for instance, proposed that rereading is necessary if we are to realize the true goal of literature, which, in his view, is to make the reader “no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text.” When we reread, we discover how a text can multiply in its variety and its plurality. Rereading offers something beyond a more detailed comprehension of the text: it is, Barthes claims, “an operation contrary to the commercial and ideological habits of our society, which would have us ‘throw away’ the story once it has been consumed (‘devoured’).” I’m not so sure. Opening her late-summer set in Gunnersbury Park, west London, PJ Harvey sang: “Wyman, am I worthy?/Speak your wordle to me.” A pink haze had settled across the sky just before she appeared onstage to the sound of birdsong, church bells, and electronic fuzz. In the lyric – which comes from “Prayer at the Gate”, the opening track of her most recent record I Inside the Old Year Dying – Harvey sings in the dialect of her native Dorset. Wyman-Elvis is a Christ-like figure, literally an all-wise warrior, who appears throughout the album, and “wordle” is the world. For the next hour and a half, as the sky darkens and Harvey and her four-piece band perform underneath a low, red-tinged moon, they conjure their own wordle, one of riddles and disquieting enchantment.

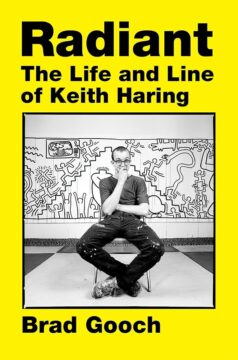

Opening her late-summer set in Gunnersbury Park, west London, PJ Harvey sang: “Wyman, am I worthy?/Speak your wordle to me.” A pink haze had settled across the sky just before she appeared onstage to the sound of birdsong, church bells, and electronic fuzz. In the lyric – which comes from “Prayer at the Gate”, the opening track of her most recent record I Inside the Old Year Dying – Harvey sings in the dialect of her native Dorset. Wyman-Elvis is a Christ-like figure, literally an all-wise warrior, who appears throughout the album, and “wordle” is the world. For the next hour and a half, as the sky darkens and Harvey and her four-piece band perform underneath a low, red-tinged moon, they conjure their own wordle, one of riddles and disquieting enchantment. The impact of this work probably has nothing to do with whether it is high art masquerading as low art or low art masquerading as high art. Haring himself never seemed particularly interested in those divisions anyway. He liked Dubuffet and Alechinsky in exactly the same way that he liked cartoons and street graffiti. Pace Kuspit, I don’t think you can say that Haring’s art was fundamentally populist with a dash of high art influence to keep it from getting stale.

The impact of this work probably has nothing to do with whether it is high art masquerading as low art or low art masquerading as high art. Haring himself never seemed particularly interested in those divisions anyway. He liked Dubuffet and Alechinsky in exactly the same way that he liked cartoons and street graffiti. Pace Kuspit, I don’t think you can say that Haring’s art was fundamentally populist with a dash of high art influence to keep it from getting stale. I

I Picture two people sitting in a movie theater, both watching the screen: Are they seeing the same thing? Or is the movie playing out differently in each of their minds? Researchers from the Justus Liebig University Giessen (JLU) have found that it’s the latter, and they’ve

Picture two people sitting in a movie theater, both watching the screen: Are they seeing the same thing? Or is the movie playing out differently in each of their minds? Researchers from the Justus Liebig University Giessen (JLU) have found that it’s the latter, and they’ve  On first opening a book I listen for the sound of the human voice. Instead of looking for signs, I form an impression of a tone, and if I can hear in that tone the harmonies of the human improvisation extended through 5,000 years of space and time, then I read the book. By this device I am absolved from reading most of what is published in a given year. I have found that few writers learn to speak in the human voice, that most of them make use of alien codes (academic, political, literary, bureaucratic, technical) in which they send messages already deteriorating into the half-life of yesterday’s news. Their transmissions seem to me incomprehensible, and unless I must decipher them for professional reasons, I am content to let them pass by. Too many subtle voices divert my attention, to the point that when I enter a bookstore I am besieged by the same sense of imminent discovery that follows me through seaports and capital cities. This restlessness never troubles me in libraries, probably because libraries are to me like museums. It is the guile of commerce that accounts for the foreboding in bookstores; I have a feeling of the marketplace, of ideas still current after 2,000 years, of old men earning passage money by telling tales of what once was the city of Antioch.

On first opening a book I listen for the sound of the human voice. Instead of looking for signs, I form an impression of a tone, and if I can hear in that tone the harmonies of the human improvisation extended through 5,000 years of space and time, then I read the book. By this device I am absolved from reading most of what is published in a given year. I have found that few writers learn to speak in the human voice, that most of them make use of alien codes (academic, political, literary, bureaucratic, technical) in which they send messages already deteriorating into the half-life of yesterday’s news. Their transmissions seem to me incomprehensible, and unless I must decipher them for professional reasons, I am content to let them pass by. Too many subtle voices divert my attention, to the point that when I enter a bookstore I am besieged by the same sense of imminent discovery that follows me through seaports and capital cities. This restlessness never troubles me in libraries, probably because libraries are to me like museums. It is the guile of commerce that accounts for the foreboding in bookstores; I have a feeling of the marketplace, of ideas still current after 2,000 years, of old men earning passage money by telling tales of what once was the city of Antioch. Alzheimer’s disease slowly takes over the mind. Long before symptoms occur, brain cells are gradually losing their function. Eventually they wither away, eroding brain networks that store memories. With time, this robs people of their recollections, reasoning, and identity. It’s not the type of forgetfulness that happens during normal aging. In the twilight years, our ability to soak up new learning and rapidly recall memories also nosedives. While the symptoms seem similar, normally aging brains don’t exhibit the classic signs of Alzheimer’s—toxic protein buildups inside and surrounding neurons, eventually contributing to their deaths. These differences can only be caught by autopsies, when it’s already too late to intervene. But they can still offer insights. Studies have built a profile of Alzheimer’s brains: Shrunken in size, with toxic protein clumps spread across regions involved in reasoning, learning, and memory.

Alzheimer’s disease slowly takes over the mind. Long before symptoms occur, brain cells are gradually losing their function. Eventually they wither away, eroding brain networks that store memories. With time, this robs people of their recollections, reasoning, and identity. It’s not the type of forgetfulness that happens during normal aging. In the twilight years, our ability to soak up new learning and rapidly recall memories also nosedives. While the symptoms seem similar, normally aging brains don’t exhibit the classic signs of Alzheimer’s—toxic protein buildups inside and surrounding neurons, eventually contributing to their deaths. These differences can only be caught by autopsies, when it’s already too late to intervene. But they can still offer insights. Studies have built a profile of Alzheimer’s brains: Shrunken in size, with toxic protein clumps spread across regions involved in reasoning, learning, and memory. I

I I was reading some Goethe recently, both in German, since I’m constantly working on my German these days for reasons not entirely clear to anyone, myself included, and also sometimes in an English translation, since it is pretty hard, actually, to read Goethe in German given the somewhat antiquated and very much literary nature of the writing. Actually, come to think of it, I haven’t really been reading Goethe. What I’ve been reading is the account of many long and short conversations between Goethe and a person named Johann Peter Eckermann, who was a youngish literary-minded fellow who sent Goethe some of his writing, writing that was rather ass-kissy in its love of, and reliance on, a Goethian way of thinking, and so Eckermann sent Goethe some of this Goethe-worshiping writing and Goethe, unsurprisingly, lapped it up and invited Eckermann to come and visit him at his fancy house in Weimar. This was in 1823 or thereabouts. Goethe was born in 1749, so this would have made him seventy-four when all this business with Eckermann took place. And then Goethe died in 1832, so there were roughly nine years of Goethe and Eckermann talking and talking and talking. The German edition of the conversations is multiple volumes and the Penguin English translation, which I think is complete, comes to 648 pages in fairly small print.

I was reading some Goethe recently, both in German, since I’m constantly working on my German these days for reasons not entirely clear to anyone, myself included, and also sometimes in an English translation, since it is pretty hard, actually, to read Goethe in German given the somewhat antiquated and very much literary nature of the writing. Actually, come to think of it, I haven’t really been reading Goethe. What I’ve been reading is the account of many long and short conversations between Goethe and a person named Johann Peter Eckermann, who was a youngish literary-minded fellow who sent Goethe some of his writing, writing that was rather ass-kissy in its love of, and reliance on, a Goethian way of thinking, and so Eckermann sent Goethe some of this Goethe-worshiping writing and Goethe, unsurprisingly, lapped it up and invited Eckermann to come and visit him at his fancy house in Weimar. This was in 1823 or thereabouts. Goethe was born in 1749, so this would have made him seventy-four when all this business with Eckermann took place. And then Goethe died in 1832, so there were roughly nine years of Goethe and Eckermann talking and talking and talking. The German edition of the conversations is multiple volumes and the Penguin English translation, which I think is complete, comes to 648 pages in fairly small print.