Matt Glassman in Matt’s Five Points:

In 2016, Nate Silver was panned in the press and on social media for his presidential election forecast. His model gave Clinton a 71% chance of winning, and she lost. He and other forecasters totally missed the Trump phenomena; the polls were off and Trump was more popular than expected. For many people, the bloom was off the rose. Silver—who had so brilliantly predicted all the details of the 2008 and 2012 elections—got it wrong. He wasn’t infallible after all.

In 2016, Nate Silver was panned in the press and on social media for his presidential election forecast. His model gave Clinton a 71% chance of winning, and she lost. He and other forecasters totally missed the Trump phenomena; the polls were off and Trump was more popular than expected. For many people, the bloom was off the rose. Silver—who had so brilliantly predicted all the details of the 2008 and 2012 elections—got it wrong. He wasn’t infallible after all.

The catch is that it was actually a great forecast. The 29% chance Silver’s model gave Trump was significantly higher than most of the other prediction models—some of which gave Clinton as much as a 99% chance to win—and, crucially, much more bullish on Trump than public betting markets in gambling houses around the globe, which thought Trump had about a 17% chance to win. If you believed Silver’s model, it was a blaring siren to bet on Trump and against the conventional wisdom. Those who followed Silver’s advice got a massive return on their investment.

This analytical split—between people who saw Silver’s 2016 forecast as a huge miss and those who understood it as astute and financially lucrative—goes to the core of his fantastic new book, On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

In the spring of 1961, Gerhard Richter, a young East German artist noted mainly for his portraits and socialist wall paintings, slipped through the last chink in the Iron Curtain—West Berlin—and fled to the Federal Republic of Germany. A few weeks later, he justified this move in a letter to his former teacher at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts: “My reasons are mainly professional. The whole cultural ‘climate’ of the West can offer me more, in that it corresponds better and more coherently with my way of being and working than that of the East.”

In the spring of 1961, Gerhard Richter, a young East German artist noted mainly for his portraits and socialist wall paintings, slipped through the last chink in the Iron Curtain—West Berlin—and fled to the Federal Republic of Germany. A few weeks later, he justified this move in a letter to his former teacher at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts: “My reasons are mainly professional. The whole cultural ‘climate’ of the West can offer me more, in that it corresponds better and more coherently with my way of being and working than that of the East.” My first visceral memories of the regime in Iran were formed before I was born. My mother had been in the notorious Evin prison in the 1980s, when hanged bodies were lined up along the entrance path so that prisoners knew what to expect. Although naturally apolitical, my mother was seen with a dissident. She narrowly escaped lynching, only because the dissident learned of my mother’s arrest and turned herself in.

My first visceral memories of the regime in Iran were formed before I was born. My mother had been in the notorious Evin prison in the 1980s, when hanged bodies were lined up along the entrance path so that prisoners knew what to expect. Although naturally apolitical, my mother was seen with a dissident. She narrowly escaped lynching, only because the dissident learned of my mother’s arrest and turned herself in. W

W T

T T

T Though bears loom large in our collective imagination, their flesh-and-blood counterparts are increasingly losing ground. Eight Bears, the debut of environmental journalist Gloria Dickie, draws on visits to key hotspots where Earth’s remaining bear species come into conflict with humans. By interviewing scores of people, both conservationists and those suffering at the paws of these large predators, this nuanced and thought-provoking reportage asks whether humans and bears can coexist.

Though bears loom large in our collective imagination, their flesh-and-blood counterparts are increasingly losing ground. Eight Bears, the debut of environmental journalist Gloria Dickie, draws on visits to key hotspots where Earth’s remaining bear species come into conflict with humans. By interviewing scores of people, both conservationists and those suffering at the paws of these large predators, this nuanced and thought-provoking reportage asks whether humans and bears can coexist. In the

In the  SEVENTY YEARS AGO, Ray Bradbury, then 33 years old—the author of The Martian Chronicles (1950), The Illustrated Man (1951), and Fahrenheit 451 (1953)—stood in front of a mirror in a London hotel room and declared, “I … am Herman Melville!” It was a last-ditch effort to channel the great American writer of Moby-Dick (1851). For Bradbury, it was either that or accept complete failure.

SEVENTY YEARS AGO, Ray Bradbury, then 33 years old—the author of The Martian Chronicles (1950), The Illustrated Man (1951), and Fahrenheit 451 (1953)—stood in front of a mirror in a London hotel room and declared, “I … am Herman Melville!” It was a last-ditch effort to channel the great American writer of Moby-Dick (1851). For Bradbury, it was either that or accept complete failure. A

A Depression doesn’t mean you’re always feeling low. Sure, most times it’s hard to crawl out of bed or get motivated. Once in a while, however, you feel a spark of your old self—only to get sucked back into an emotional black hole. There’s a reason for this variability. Depression changes brain connections, even when the person is feeling okay at the moment. Scientists have long tried to map these alternate networks. But traditional brain mapping technologies average multiple brains, which doesn’t capture individual brain changes.

Depression doesn’t mean you’re always feeling low. Sure, most times it’s hard to crawl out of bed or get motivated. Once in a while, however, you feel a spark of your old self—only to get sucked back into an emotional black hole. There’s a reason for this variability. Depression changes brain connections, even when the person is feeling okay at the moment. Scientists have long tried to map these alternate networks. But traditional brain mapping technologies average multiple brains, which doesn’t capture individual brain changes. In 2009, A US security intelligence operative stationed in Iraq began to notice some gaps in the American government’s “surgical precision” drone strategy. “I was trained to be an all-source analyst,” writes Chelsea Manning in her memoir, README.TXT (2022). “I’m used to collecting the full context and getting—and sharing—as much detail as possible.”

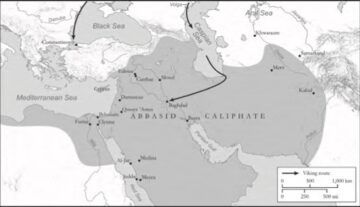

In 2009, A US security intelligence operative stationed in Iraq began to notice some gaps in the American government’s “surgical precision” drone strategy. “I was trained to be an all-source analyst,” writes Chelsea Manning in her memoir, README.TXT (2022). “I’m used to collecting the full context and getting—and sharing—as much detail as possible.” In the eighth-century CE the Abbasids undertook to collect the wisdom of the world in their new capital at Baghdad. This project started with the second Abbasid caliph, al-Mansur (“the Conqueror,” r. 754–74), who commissioned Arabic translations of important scientific texts from Persian, Sanskrit, Greek, and Syriac (a late form of Aramaic), and came into its own under al-Ma’mun (“the Trusted One,” r. 813–33).

In the eighth-century CE the Abbasids undertook to collect the wisdom of the world in their new capital at Baghdad. This project started with the second Abbasid caliph, al-Mansur (“the Conqueror,” r. 754–74), who commissioned Arabic translations of important scientific texts from Persian, Sanskrit, Greek, and Syriac (a late form of Aramaic), and came into its own under al-Ma’mun (“the Trusted One,” r. 813–33). O

O