Kristen French in Nautilus:

Throw on the Power Lights! Rev her up to 8,500! We’re going through!” shouts the commander to his crew, as he navigates through the worst storm in his 20 years of flying. A harrowing scene unfolds but then Walter Mitty is brought back to reality by the sound of his wife’s voice, the daydream fading into the byways of his mind. Not long after that, he’s struck with a new fantasy, and then another. Over the course of an afternoon, while running mundane errands, Mitty proceeds to have a series of increasingly dazzling daydreams in which he performs acts of great heroism, vivid narratives that bubble like a geyser into his mind.

This is the plot of “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” a short story written by James Thurber in 1939 that has been retold over and over in popular film and theater adaptations. The story has captured so many imaginations because getting lost in daydreams is a very human thing to do. We all occasionally script narratives in our minds in which our deepest desires come true, as a refuge from some of the more disappointing facts of life.

For some, though, the delight of daydreaming can turn into a curse: The fantasies become such a successful form of escape that they take over the mind, becoming compulsive and preventing the dreamer from paying attention to important facets of reality—work, school, other people.

Psychologists have been fascinated with daydreams since at least the time of Freud, who believed they bore the hallmarks of unconscious yearnings and conflicts. But Israeli research and clinical psychologist Eli Somer was the first to describe excessive daydreaming as a distinct psychiatric problem.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Many writers’ graves are

Many writers’ graves are  I

I Welcome to Lit Trivia, the Book Review’s regular quiz about books, authors and literary culture. This week’s installment challenges you to identify classic novels from the descriptions in their original — and, well, not wholly positive — reviews in the pages of The New York Times. In the five multiple-choice questions below, tap or click on the answer you think is correct. After the last question, you’ll find links to the books if you’d like to do some further reading.

Welcome to Lit Trivia, the Book Review’s regular quiz about books, authors and literary culture. This week’s installment challenges you to identify classic novels from the descriptions in their original — and, well, not wholly positive — reviews in the pages of The New York Times. In the five multiple-choice questions below, tap or click on the answer you think is correct. After the last question, you’ll find links to the books if you’d like to do some further reading. A problem most of us have, perhaps especially women, is that when we are in the mood to have sex reinvent our lives—when we feel dirty, restless, eager to be used and witnessed—we lay around wishing for someone intuitive and creative to come along and recognize a kindred spirit in us. We walk into bars and parties as if we’re adolescents hoping to be recognized on the street by a talent scout. We know that if someone would just give us what we want, without us having to describe it, we would amaze them and ourselves. It humiliates and disappoints us when everyone who comes sniffing just feels “kind of… cheesy,” as you put it. The intention of sex voice is to conjure a mutual fantasy, to invoke a shared scene—but the question remains: Whose scene is it? We each have the opportunity (and, really, the imperative) to direct the erotic scene for ourselves—and this includes women who wish on the whole to be submissive. I don’t mean leading in sex; I mean adjusting, with a light touch, the direction in which we hope the scene will tend.

A problem most of us have, perhaps especially women, is that when we are in the mood to have sex reinvent our lives—when we feel dirty, restless, eager to be used and witnessed—we lay around wishing for someone intuitive and creative to come along and recognize a kindred spirit in us. We walk into bars and parties as if we’re adolescents hoping to be recognized on the street by a talent scout. We know that if someone would just give us what we want, without us having to describe it, we would amaze them and ourselves. It humiliates and disappoints us when everyone who comes sniffing just feels “kind of… cheesy,” as you put it. The intention of sex voice is to conjure a mutual fantasy, to invoke a shared scene—but the question remains: Whose scene is it? We each have the opportunity (and, really, the imperative) to direct the erotic scene for ourselves—and this includes women who wish on the whole to be submissive. I don’t mean leading in sex; I mean adjusting, with a light touch, the direction in which we hope the scene will tend.

T

T In the more than six million years since people and chimpanzees split from their common ancestor, human brains have rapidly amassed tissue that helps decision-making and self-control. But the same regions are also the most at risk of deterioration during ageing, finds a study

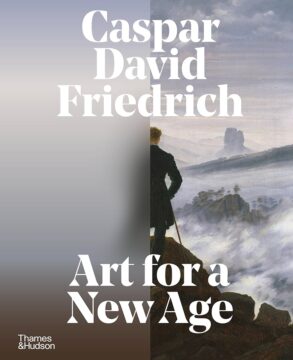

In the more than six million years since people and chimpanzees split from their common ancestor, human brains have rapidly amassed tissue that helps decision-making and self-control. But the same regions are also the most at risk of deterioration during ageing, finds a study The German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), who is celebrated in these two books published to accompany the exhibitions in Hamburg and Berlin marking the 250th anniversary of his birth, has fascinated me all my life. When I was at school, his mysterious and emotive paintings started to appear on the covers of the grey-spined Penguin Modern Classics series: Abbey in the Oakwood on the cover of Hermann Hesse’s Narziss and Goldmund; Woman at a Window (the woman’s back turned, one shutter open to the spring morning and the riverbank) on that of Thomas Mann’s Lotte in Weimar. Covers featuring Sea of Ice, with its unfathomable grey-blue sky, and the yearning, autumnal Moonwatchers soon followed. Every image was memorable; every one hinted at emotional and spiritual depths embodied in northern European landscapes and places.

The German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), who is celebrated in these two books published to accompany the exhibitions in Hamburg and Berlin marking the 250th anniversary of his birth, has fascinated me all my life. When I was at school, his mysterious and emotive paintings started to appear on the covers of the grey-spined Penguin Modern Classics series: Abbey in the Oakwood on the cover of Hermann Hesse’s Narziss and Goldmund; Woman at a Window (the woman’s back turned, one shutter open to the spring morning and the riverbank) on that of Thomas Mann’s Lotte in Weimar. Covers featuring Sea of Ice, with its unfathomable grey-blue sky, and the yearning, autumnal Moonwatchers soon followed. Every image was memorable; every one hinted at emotional and spiritual depths embodied in northern European landscapes and places.