Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Jeremy Strong on Taking a Risk With a New Film About Trump

Eliana Dockterman in Time Magazine:

Jeremy Strong is not known for his sense of humor. When getting dressed, he favors brown for its “monastic” connotation. He famously thought that Succession, the HBO show that shot him to stardom, was a straight drama when his co-stars believed it to be a comedy. When he sits down for our Zoom conversation in September—in a brown shirt, of course—he recites poetry and quotes Stella Adler, the godmother of Method acting. He describes Succession as reflecting “the Emersonian notion of the institution as the shadow of a man.”

Jeremy Strong is not known for his sense of humor. When getting dressed, he favors brown for its “monastic” connotation. He famously thought that Succession, the HBO show that shot him to stardom, was a straight drama when his co-stars believed it to be a comedy. When he sits down for our Zoom conversation in September—in a brown shirt, of course—he recites poetry and quotes Stella Adler, the godmother of Method acting. He describes Succession as reflecting “the Emersonian notion of the institution as the shadow of a man.”

But when I suggest that he could have capitalized on that show’s success by earning a hefty paycheck from a superhero movie—as many in his position have done—he cracks a self-aware smile. The notion that he, an actor who insists on disposing of his own personality in order to fully inhabit a character, would implement that extreme approach to play a spandex-wearing hero is, indeed, funny.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Nanoparticles Breathe New Life into Lungs

Sneha Khedkar in The Scientist:

In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration approved Trikafta for patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) who have the most common disease-causing mutation. Trikafta targets the defective protein—a misfolded form of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)—produced as a result of this mutation.1 However, people with other mutations in the CFTR gene, including those with variants that result in no proteins being made at all, cannot benefit from the drug. “Therefore, interest is being placed on genetic therapies,” said Daniel Siegwart, a chemist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Current gene therapy methods involve delivering mutation-correcting gene-editing tools directly to lung cells. However, such tools are often administered through inhalation and struggle to cross the thick, sticky mucus on their way to the cells.2 Now, in a paper published in Science, Siegwart and his team showed that lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) delivered intravenously successfully delivered gene-editing tools to all lung cell types, including stem cells.3 This approach enabled long-lasting gene correction in a mouse model of CF and in patient cells. The LNP-based system offers new therapeutic avenues for delivering gene-editing tools to specific tissues.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Constant Confession

Aaron Neiman at Aeon Magazine:

Foucault was greatly disturbed by modern psychiatry’s ability to draw definitive lines between the ‘reasonable’ and the ‘unreasonable’. He came to see it as another way for society to punish and marginalise its most troublesome subjects. Deploying the metaphor of a circulatory system, he conceived of psychiatrists as figures of ‘capillary’ power – unlike the conspicuous, beating heart of the state, these authorities functioned as more subtle, distal agents of the status quo. Writing in the 1960s and ’70s, Foucault saw the psychoanalytic therapists of his day as the latest technicians managing ‘one of the West’s most highly valued techniques for producing truth of one kind or another’ – the confession. This is the idea that disclosing one’s inner darkness leads to salvation, truth, self-actualisation. There is an important similarity between how this dynamic plays out in the church and the clinic: ‘bravely confront and share the ugly things inside you’ equally describes the task of the confessional booth as it does the therapist’s couch. In both cases, there is more at play here than simple unburdening: it is not just that ‘shared sorrow is half sorrow’, as in the case of confiding in a friend, but also that having an adversarial encounter with yourself can be fruitful in some way.

Foucault was greatly disturbed by modern psychiatry’s ability to draw definitive lines between the ‘reasonable’ and the ‘unreasonable’. He came to see it as another way for society to punish and marginalise its most troublesome subjects. Deploying the metaphor of a circulatory system, he conceived of psychiatrists as figures of ‘capillary’ power – unlike the conspicuous, beating heart of the state, these authorities functioned as more subtle, distal agents of the status quo. Writing in the 1960s and ’70s, Foucault saw the psychoanalytic therapists of his day as the latest technicians managing ‘one of the West’s most highly valued techniques for producing truth of one kind or another’ – the confession. This is the idea that disclosing one’s inner darkness leads to salvation, truth, self-actualisation. There is an important similarity between how this dynamic plays out in the church and the clinic: ‘bravely confront and share the ugly things inside you’ equally describes the task of the confessional booth as it does the therapist’s couch. In both cases, there is more at play here than simple unburdening: it is not just that ‘shared sorrow is half sorrow’, as in the case of confiding in a friend, but also that having an adversarial encounter with yourself can be fruitful in some way.

This uneasy brush with the self, mediated through a person with social authority, is an essential feature of these confessional practices, and distinguishes them from other kinds of dialogue. Therapy is based on this same model: it is carefully choreographed around a highly skilled worker, one with the practical knowledge and symbolic authority to endow this interaction with the gravity it deserves.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Revisiting ‘Citizen,’ 10 Years Later

Maria Siciliano at The Millions:

Representing suffering—how to do it, when we should do it at all—has long been a subject of debate. At the center of that debate is the role of the audience: how do we, as readers and viewers, witness depictions of violence in images, films, plays, or literature?

Representing suffering—how to do it, when we should do it at all—has long been a subject of debate. At the center of that debate is the role of the audience: how do we, as readers and viewers, witness depictions of violence in images, films, plays, or literature?

In On Photography, Susan Sontag suggests that the act of looking, from a distance, is self-regarding. For writer and photographer Teju Cole, this visual and affective act is limited in what it can connote. Joining Sontag in conversation, Cole argues in Black Paper that the visual illustrates without condemning, becoming a collection of violence for consumption. But he ultimately concludes that in many ways, bearing witness to the existence of this suffering is better than ignoring its reality. Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric—a hybrid work of poetry, prose, and visual art—boldly considered these questions, and many others, through its use of language and form. Recounting a series of mounting racial slights and aggressions, endured in daily life and in the media, the book has proven both prescient and timeless.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

So Live Your Life

So live your life that the fear of death

can never enter your heart. Trouble

no one about their religion; respect

others in their view, and demand

that they respect yours.

Love your life, perfect your life,

beautify all things in your life.

Seek to make your life long

and its purpose in the service

of your people.

Prepare a noble death song for the day

when you go over the great divide.

Always give a word or a sign of salute

when meeting or passing a friend, even

a stranger, when in a lonely place.

Show respect to all people

and grovel to none.

When you arise in the morning

give thanks for the food and for

the joy of living.

If you see no reason for giving thanks,

the fault lies only in yourself. Abuse

no one and no thing, for abuse turns

the wise ones to fools and robs

the spirit of its vision.

When it comes your time to die,

be not like those whose hearts

are filled with the fear of death,

so that when their time comes

they weep and pray for a little

more time to live their lives

over again in a

different way.

Sing your death song and die

like a hero going home.

Chief Tecumseh

from Poetic Outlaws

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Making of “Citizen”: Claudia Rankine

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, October 14, 2024

What Good Is Great Literature?

A.O. Scott in the New York Times:

The Swedish Academy is not here to tell you what writers you might like. Greatness is not the same as popularity. It may even be the opposite of popularity. Great books are by definition not the books you read for pleasure — even if some of them turn out to be, and may even have been intended to be, fun — and great writers, being mostly dead, don’t care if they’re your favorites. The great books are the ones you’re supposed to feel bad about not having read. Great writers are the ones who matter whether you read them or not.

The Swedish Academy is not here to tell you what writers you might like. Greatness is not the same as popularity. It may even be the opposite of popularity. Great books are by definition not the books you read for pleasure — even if some of them turn out to be, and may even have been intended to be, fun — and great writers, being mostly dead, don’t care if they’re your favorites. The great books are the ones you’re supposed to feel bad about not having read. Great writers are the ones who matter whether you read them or not.

How strange. And yet, how normal. “It is natural to believe in great men,” Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote. “We call our children and our lands by their names. Their names are wrought into the verbs of language, their works and effigies are in our houses, and every circumstance of the day recalls an anecdote of them.” That’s from the beginning of “Representative Men,” an 1850 collection of essays, influenced by Thomas Carlyle’s “On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History,” that pursues the principle of greatness through time, locating it in a half-dozen exemplary individuals.

Given Emerson’s title and his times, it’s not surprising that all his exemplars are male. But it is notable that most are writers and thinkers, including Plato, Montaigne, Shakespeare and Goethe and Emerson’s favorite, the theologian Emanuel Swedenborg. Napoleon is the only political leader in the group, perhaps in keeping with a mid-19th-century New Englander’s temperamental mistrust of monarchic or imperial power.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How Learning Can Guide Evolution

An interesting 1987 paper by this year’s physics Nobel laureate Geoffrey E. Hinton, and Steven J. Nowlan:

Many organisms learn useful adaptations during their lifetime. These adaptations are often the result of an exploratory search which tries out many possibilities in order to discover good solutions. It seems very wasteful not to make use of the exploration performed by the phenotype to facilitate the evolutionary search for good genotypes. The obvious way to achieve this is to transfer information about the acquired characteristics back to the genotype. Most biologists now accept that the Lamarckian hypothesis is not substantiated; some then infer that learning cannot guide the evolutionary search. We use a simple combinatorial argument to show that this inference is incorrect and that learning can be very effective in guiding the search, even when the specific adaptations that are learned are not communicated to the genotype. In difficult evolutionary searches which require many possibilities to be tested in order to discover a complex co-adaptation, we demonstrate that each learning trial can be almost as helpful to the evolutionary search as the production and evaluation of a whole new organism. This greatly increases the efficiency of evolution because a learning trial is much faster and requires much less expenditure of energy than the production of a whole organism.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The U.S. Election Abroad: Twelve writers tell us what the race between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris looks like where they live

From The Dial:

The U.S. presidential election is decided by American citizens in a handful of states, but its outcome reverberates internationally: the new president will have the power to shape trade, migration, security and rising authoritarianism across the world, as well as the wars in Gaza and Ukraine. The race is therefore a global event, the subject of countless newspaper articles, debates and calculations. We asked 12 writers, each from a different country, to share what the conversation sounds like where they live: What are politicians saying, and how is the press covering the race? What are the hopes for a Kamala Harris presidency, or a Donald Trump one — and what are the fears? Our writers describe widely divergent attitudes toward the election and its unknown conclusion, from apathy and disillusionment to anxiety, hope and glee.

The U.S. presidential election is decided by American citizens in a handful of states, but its outcome reverberates internationally: the new president will have the power to shape trade, migration, security and rising authoritarianism across the world, as well as the wars in Gaza and Ukraine. The race is therefore a global event, the subject of countless newspaper articles, debates and calculations. We asked 12 writers, each from a different country, to share what the conversation sounds like where they live: What are politicians saying, and how is the press covering the race? What are the hopes for a Kamala Harris presidency, or a Donald Trump one — and what are the fears? Our writers describe widely divergent attitudes toward the election and its unknown conclusion, from apathy and disillusionment to anxiety, hope and glee.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Ed Yong talks about his seven rules for being a public figure in a time of crisis

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Don’t Waste Your Wildness

Maria Popova at The Marginalian:

Jay Griffiths offers a mighty antidote in her 2006 masterpiece Wild: An Elemental Journey (public library) — the product of “many years’ yearning” pulling her “toward unfetteredness, toward the sheer and vivid world,” learning to think with the mind of a mountain and feel with the heart of a forest, searching for “something shy, naked and elemental — the soul.” What emerges is both an act of revolt (against the erasure of the wild, against the domestication of the soul) and an act of reverence (for the irrepressible in nature, for landscape as a form of knowledge, for life on Earth, as improbable and staggering as love.)

Jay Griffiths offers a mighty antidote in her 2006 masterpiece Wild: An Elemental Journey (public library) — the product of “many years’ yearning” pulling her “toward unfetteredness, toward the sheer and vivid world,” learning to think with the mind of a mountain and feel with the heart of a forest, searching for “something shy, naked and elemental — the soul.” What emerges is both an act of revolt (against the erasure of the wild, against the domestication of the soul) and an act of reverence (for the irrepressible in nature, for landscape as a form of knowledge, for life on Earth, as improbable and staggering as love.)

A century and a half after Thoreau “went to the woods to live deliberately” (omitting from his famed chronicle of spartan solitude the fresh-baked doughnuts and pies his mother and sister brought him every Sunday), Griffiths spent seven years slaking her soul on the world’s wildness, from the Amazon to the Arctic, trying “to touch life with the quick of the spirit,” impelled by “the same ancient telluric vigor that flung the Himalayas up to applaud the sky.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Commit Lit: In search of higher education

Joseph Keegin in The Point:

In 2012, at the age of 25, I quit my part-time jobs cooking and cleaning houses and, having dropped out during my first semester seven years earlier, went back to school. To help pay for the modest tuition at Indiana University Southeast in New Albany, Indiana, I took a work-study gig at the university library. The campus of IUS is small, and most students are commuters; the library was accordingly quiet, the work languid. So in the many slow periods between tasks, I read. Essays, stories, poems—whatever I could get my hands on. My reading was omnivorous and unstructured: like the critics in the first part of Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, I pursued knowledge like sleuths in a roman noir, or like the poet Juan García Madero from his Savage Detectives, for whom “every book in the world is out there waiting to be read by me.” I followed a friend onto Twitter—the early 140-character years, with few journalists and politicians and no blue checkmarks—and there I came into contact for the first time with the world of magazines, small and large, that constituted the internal chatter of the educated American upper-middle class.

In 2012, at the age of 25, I quit my part-time jobs cooking and cleaning houses and, having dropped out during my first semester seven years earlier, went back to school. To help pay for the modest tuition at Indiana University Southeast in New Albany, Indiana, I took a work-study gig at the university library. The campus of IUS is small, and most students are commuters; the library was accordingly quiet, the work languid. So in the many slow periods between tasks, I read. Essays, stories, poems—whatever I could get my hands on. My reading was omnivorous and unstructured: like the critics in the first part of Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, I pursued knowledge like sleuths in a roman noir, or like the poet Juan García Madero from his Savage Detectives, for whom “every book in the world is out there waiting to be read by me.” I followed a friend onto Twitter—the early 140-character years, with few journalists and politicians and no blue checkmarks—and there I came into contact for the first time with the world of magazines, small and large, that constituted the internal chatter of the educated American upper-middle class.

Amid this cacophony of culture-talk—heard from a remove, like music from a distant room—I began to discern a theme. I listened, equally interested and perplexed. It concerned the state of American higher education: plummeting enrollment in English, philosophy, history and other bookish, scholarly disciplines leading to the annulment of programs and the shuttering of departments; skyrocketing tuition and ballooning student debt; a pervasive sense of panic and despair.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Palestinian Photographer Reflects on One Year of Life and Death in Gaza

Yasmeen Serhan in Time Magazine:

A year later, the 28-year-old is still documenting the lived experience of Palestinians in a place with scars visible from space. But for all of the images of physical destruction, Alghorra’s most profound photographs are of the human impact. In one, he found a Palestinian child crying in the rain as she and others wait for food to be distributed outside a refugee camp in the southernmost city of Rafah. Insufficient humanitarian aid reaching the Strip means that for most people, one meal a day is the most they can hope for. Dozens of children have died of starvation.

A year later, the 28-year-old is still documenting the lived experience of Palestinians in a place with scars visible from space. But for all of the images of physical destruction, Alghorra’s most profound photographs are of the human impact. In one, he found a Palestinian child crying in the rain as she and others wait for food to be distributed outside a refugee camp in the southernmost city of Rafah. Insufficient humanitarian aid reaching the Strip means that for most people, one meal a day is the most they can hope for. Dozens of children have died of starvation.

In another photo, a Palestinian family sits in the living room of their dilapidated home in Khan Yunis. The walls are scorched black and the infrastructure is crumbling, but it’s preferable to the alternative—the crowded tents where the vast majority of people in Gaza, including Alghorra, are now living. Since being forced to leave his home in Gaza City in the early days of the war, he now shares a tent with colleagues next to the Nasser Medical Complex, one of Gaza’s last remaining hospitals.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Bioregional Belonging With Jay Griffiths

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Elements of Marie Curie

Wendy Moore at Literary Review:

Marie Curie’s life was defined by professional triumph and personal tragedy. Ninety years after her death, she remains history’s most famous woman scientist. Curie was the first woman to receive a Nobel Prize – in 1903, she and her husband, Pierre, received the award for physics. In 1911, she was awarded a second Nobel Prize, this time for chemistry. She is still the only Nobel laureate to be garlanded in two scientific fields.

Marie Curie’s life was defined by professional triumph and personal tragedy. Ninety years after her death, she remains history’s most famous woman scientist. Curie was the first woman to receive a Nobel Prize – in 1903, she and her husband, Pierre, received the award for physics. In 1911, she was awarded a second Nobel Prize, this time for chemistry. She is still the only Nobel laureate to be garlanded in two scientific fields.

Yet after her husband’s death in a freak traffic accident in 1906, just eleven years into their marriage, she led a sorrowful and often lonely existence dedicated to continuing the work they had begun together. Meeting Curie in 1920, an American journalist described her as ‘a pale, timid little woman in a black cotton dress, with the saddest face I had ever looked upon’. She was selfless and self-effacing too. When asked to write an autobiography, Curie dictated a single paragraph: ‘I was born in Warsaw of a family of teachers. I married Pierre Curie and had two children. I have done my work in France.’

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, October 13, 2024

Marshall Plans

Kate Mackenzie and Tim Sahay in Polycrisis:

At September’s UN General Assembly in New York, Brazil’s President Lula described the international financial system as a “Marshall Plan in reverse” in which the poorest countries finance the richest. Driving the point home, Lula thundered, “African countries borrow at rates up to eight times higher than Germany and four times higher than the United States.”

Lula is not alone in this diagnosis. Centrist technocrats par excellence Larry Summers & NK Singh coauthored a report earlier this year arguing that the development world’s mantra to scale up direct financing to the global South—from “billions to trillions”—has failed. Instead, global finance seems to be running in the opposite direction, from poor to rich countries, as was the case last year. Summers and Singh summarize the arrangement thusly: “millions in, billions out.” Added to this is the great global shift to austerity that makes a mockery of climate and development goals.

It’s in this context that talk of “green Marshall Plans”—proposed by Huang Yiping in China and Brian Deese in the US—must be received. Negotiations over technology transfer, market access, and finance deals are a permanent feature of the new cold war: call it strategic green industrial diplomacy.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Reckoning with Growth

Steve Keen in The Ideas Letter:

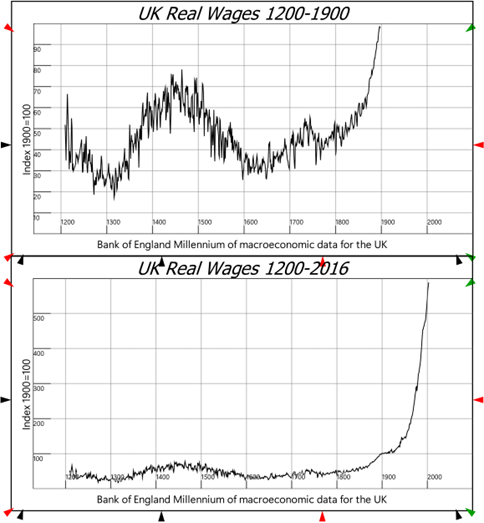

Daniel Susskind’s new book, Growth: A Reckoning (2024), opens with an important question about a remarkable fact: why did the real incomes of ordinary people in the United Kingdom rise so rapidly from the mid-1700s on, after many millennia of effective stagnation?

People struggling with the cost-of-living crisis today might not believe this is true, but Susskind illustrates this fact with data from the Bank of England’s excellent Millenium of Macroeconomic Data project. Using historical records on basic consumption items, the Bank of England indexed real wages to 100 in 1900, and showed that, though wages fluctuated over time, between 1200 and the late 1800s, the real wage never exceeded 80% of its 1900 level. Then, with a take-off that can be dated back to the mid-1700s, real wages rose dramatically, to six times the 1900 level by the year 2000, as Figure 1 illustrates.

Susskind observes that, though there had been 600 years of dramatic change before 1750, these changes did not increase the standard of living of the ordinary citizen of England…

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Discounting as a Political Technology: An Interview with Liliana Doganova

Alperen Arslan and Zac Endter in the blog of the Journal of the History of Ideas:

Liliana Doganova is Associate Professor at the Centre de sociologie de l’innovation, Mines Paris, PSL University, working at the intersection of economic sociology and Science and Technology Studies. Doganova spoke with Alperen Arslan and Zac Endter about her recent book, Discounting the Future: The Ascendancy of a Political Technology (Zone Books, 2024), which explores the links between valuation and temporality through a historical sociology of the technique of discounting the future.

Alperen Arslan and Zac Endter: Besides “discounting,” the word that seems to recur the most often in your book is some version of “crisis.” You present your book as a conscious political intervention in the present as well as a historical and theoretical one. This seems to be performed by your conceptualization of discounting as both a political theory of action and an economic theory of value. Given that this book consciously intervenes in a moment of urgency, could you share what brought you to this topic originally and how these crises or your understanding of them have evolved during your research?

Liliana Doganova: The book opens with a scene of crisis: the forest fires that devastated France in the summer of 2022. It introduces discounting through its implications in the broader climate crisis. Discounting is an economic technique that derives the value of things (including corporate investment projects, public policies, or even human life or nature) by projecting the flows of costs and benefits that they are likely to generate in the future; flows that occur at different points in time are made commensurate by being “discounted” to their so-called “present value”: the more distant a flow in the future, the less its value in the present.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

James Magee (1945 – 2024) Artist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.