Silver Maple, Solstice

And still, forty years later, I lean

my cheek to your trunk, breathe

familiar summer. I imagine the sap

pulse running through, what your roots

tell the lake, what they told the other

two other maples you once knew,

network of under earth shared

in the black of Michigan soil. Storms

stole them, trunks yanked back

from decades. Lightning severed,

both fell with such protest they took

a house right down to its stone

basement heart. They never wanted to go.

I share this with them. I share

this with you. Keep up in gale and ice,

hundreds high. Hold fast in spring’s

torment wind. Abandon any blight.

Attend only to the insects

that adore, the birds that make

respectful nests. I say this all as I round

you, touch a secret I don’t want to admit:

one small rusted nail. You’ve grown

around it, taken the scar as a mossed beauty.

But I remember the story another way:

the tin sign it held after we hammered

it into you: Payne Cottage, est. 1982.

Forgive us for wanting to claim

what was never grown for owning.

Forgive us for attempting to harness majesty,

believing it was anything but yours.

by Julie Bloemeke

from Echotheo Review

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

In 1999, nearly a decade after he first devoted himself to poetry, Phillips drove through a blizzard to interview the poet

In 1999, nearly a decade after he first devoted himself to poetry, Phillips drove through a blizzard to interview the poet  T

T Academic philosophers—people for whom philosophy is a profession—like to joke about their discomfort on airplanes. As you make light conversation with your neighbor, the question of what you do for a living tends to come up, and then you have to cope with other people’s ideas about what it is to “do philosophy.” A friend from graduate school confessed that he hated these conversations so much he would pretend to be a mathematician. (Why not a financial adviser or a travel agent?) A colleague from my first job at Johns Hopkins would head things off by saying “I teach philosophy” rather than “I am a philosopher.” It definitely sounds more approachable. But when I still felt the novelty of being a professional philosopher—and pride at having survived the rigors of graduate school—I was not about to dumb it down. I was even eager to tell people I was a philosopher. Follow-up questions fell within a range: Who are your favorite philosophers? Does anyone listen to you? Isn’t that a job from the olden days?

Academic philosophers—people for whom philosophy is a profession—like to joke about their discomfort on airplanes. As you make light conversation with your neighbor, the question of what you do for a living tends to come up, and then you have to cope with other people’s ideas about what it is to “do philosophy.” A friend from graduate school confessed that he hated these conversations so much he would pretend to be a mathematician. (Why not a financial adviser or a travel agent?) A colleague from my first job at Johns Hopkins would head things off by saying “I teach philosophy” rather than “I am a philosopher.” It definitely sounds more approachable. But when I still felt the novelty of being a professional philosopher—and pride at having survived the rigors of graduate school—I was not about to dumb it down. I was even eager to tell people I was a philosopher. Follow-up questions fell within a range: Who are your favorite philosophers? Does anyone listen to you? Isn’t that a job from the olden days? A

A CISCO BRADLEY’S The Williamsburg Avant-Garde: Experimental Music and Sound on the Brooklyn Waterfront (2023) chronicles a vital and now-vanished facet of American musical and cultural history in New York City from the mid-1980s to 2015. The book investigates how, amid hypercommercialism and mutating audio technologies, bold musicians, expert and amateur alike, impelled by a big-hearted DIY ethos, made new, imaginative music as public, independent, and free as possible by exploiting urban niches and cultural interstices, using dive bars, loft spaces, garages, warehouses, restaurants, and cafés as musical laboratories for experiments in sound, installation, and performance.

CISCO BRADLEY’S The Williamsburg Avant-Garde: Experimental Music and Sound on the Brooklyn Waterfront (2023) chronicles a vital and now-vanished facet of American musical and cultural history in New York City from the mid-1980s to 2015. The book investigates how, amid hypercommercialism and mutating audio technologies, bold musicians, expert and amateur alike, impelled by a big-hearted DIY ethos, made new, imaginative music as public, independent, and free as possible by exploiting urban niches and cultural interstices, using dive bars, loft spaces, garages, warehouses, restaurants, and cafés as musical laboratories for experiments in sound, installation, and performance.

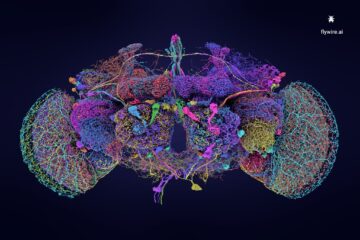

A fruit fly’s brain is smaller than a poppy seed, but it packs tremendous complexity into that tiny space. Over 140,000 neurons are joined together by more than 490 feet of wiring, as long as four blue whales placed end to end.

A fruit fly’s brain is smaller than a poppy seed, but it packs tremendous complexity into that tiny space. Over 140,000 neurons are joined together by more than 490 feet of wiring, as long as four blue whales placed end to end. When Bernie Sanders was asked in a 2016 Democratic presidential debate what “democratic socialism” meant to him, he

When Bernie Sanders was asked in a 2016 Democratic presidential debate what “democratic socialism” meant to him, he  In 2021,

In 2021, The Nobel prize has been awarded in three scientific fields —

The Nobel prize has been awarded in three scientific fields —  Ars Technica: People who are not mathematically inclined usually see all those abstract symbols and their eyes glaze over. Let’s talk about the nature of symbols in math and why becoming more familiar with mathematical notation can help non-math people surmount that language barrier.

Ars Technica: People who are not mathematically inclined usually see all those abstract symbols and their eyes glaze over. Let’s talk about the nature of symbols in math and why becoming more familiar with mathematical notation can help non-math people surmount that language barrier.  The climate debate is in a strange place. We’re told we face an epochal, civilization-ending calamity within our lifetimes. But when scientists bring up unconventional new ways of managing that risk, we’re told we mustn’t even talk about them.

The climate debate is in a strange place. We’re told we face an epochal, civilization-ending calamity within our lifetimes. But when scientists bring up unconventional new ways of managing that risk, we’re told we mustn’t even talk about them.