A O Scott in The New York Times:

On Thursday, the Swedish Academy will award the Nobel Prize in Literature, the pre-eminent — perhaps only — global arbiter of literary greatness.

On Thursday, the Swedish Academy will award the Nobel Prize in Literature, the pre-eminent — perhaps only — global arbiter of literary greatness.

What distinguishes the Nobel isn’t that it singles out the best new poems, novels, essays and plays — that kind of reader service is the job of the National Book Awards, the Booker, the Pulitzer and the dozens of other worthy prizes that crowd the calendar. The academy does not celebrate great books; it consecrates great writers, compiling not a canon but a pantheon, not a reading list but a roster of immortals.

It’s easy enough to second-guess the choices, to count the past winners who have fallen into obscurity (no disrespect to Salvatore Quasimodo) and list the non-winners who have stuck around for posterity (Vladimir Nabokov was totally robbed). Questioning the wisdom of the Nobel Committee is a cherished paraliterary ritual, along with guilt-buying the works of an author you’ve never heard of. (I swear I’ll get to Jon Fosse, as soon as I’m done with Herta Müller and Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio.) Mostly, though, the busy and distracted reading public is content to take the learned Swedes at their word, to balance skepticism and bewilderment — wait, who? — with a measure of relief. We can rest assured that, for one more year, an important cultural principle has been upheld.

But what purpose does the principle serve? What good is greatness?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

It was during the 1930s that Chartwell mattered most. Churchill was out of office. He had a flat in London but no official residence and, for much of the time, no particular reason to be in the capital. Chartwell was not, though, a retreat from the world. It was a kind of factory, filled with secretaries and research assistants who hammered Churchill’s literary and political productions into shape. It was also a meeting place – close enough to London for people to come down for lunch, dinner or an evening of conspiracy. It was, to a large extent, at Chartwell that Churchill plotted his political campaigns of the decade. Two of these were misguided. He sought to resist the limited reforms that the Baldwin government proposed to British rule in India and to defend Edward VIII during the crisis that sprang from the king’s insistence on marrying an American divorcée. Another campaign he led from there – against the appeasement of Nazi Germany and in favour of British rearmament – would, in retrospect, be seen as the most important in interwar British politics.

It was during the 1930s that Chartwell mattered most. Churchill was out of office. He had a flat in London but no official residence and, for much of the time, no particular reason to be in the capital. Chartwell was not, though, a retreat from the world. It was a kind of factory, filled with secretaries and research assistants who hammered Churchill’s literary and political productions into shape. It was also a meeting place – close enough to London for people to come down for lunch, dinner or an evening of conspiracy. It was, to a large extent, at Chartwell that Churchill plotted his political campaigns of the decade. Two of these were misguided. He sought to resist the limited reforms that the Baldwin government proposed to British rule in India and to defend Edward VIII during the crisis that sprang from the king’s insistence on marrying an American divorcée. Another campaign he led from there – against the appeasement of Nazi Germany and in favour of British rearmament – would, in retrospect, be seen as the most important in interwar British politics. In ‘As a Woman Grows Older’, the second story in J.M. Coetzee’s very funny 2023 book The Pole and Other Stories, Elizabeth Costello complains to her son John:

In ‘As a Woman Grows Older’, the second story in J.M. Coetzee’s very funny 2023 book The Pole and Other Stories, Elizabeth Costello complains to her son John: W

W To make the solar cells that are projected to become the world’s biggest source of electricity by 2031, you first melt down sand until it looks like chunks of graphite. Next, you refine it until impurities have been reduced to just one atom out of every 100 million — a form of elemental silicon known as polysilicon. It’s so vital to the production of solar panels that it can be likened to crude oil’s role in making gasoline. The polysilicon is then drawn out into a vast crystal, resembling a Jeff Koons steel sculpture of a sausage, before being sliced into salami-thin wafers. These are then treated, printed with electrodes, and finally sandwiched between glass.

To make the solar cells that are projected to become the world’s biggest source of electricity by 2031, you first melt down sand until it looks like chunks of graphite. Next, you refine it until impurities have been reduced to just one atom out of every 100 million — a form of elemental silicon known as polysilicon. It’s so vital to the production of solar panels that it can be likened to crude oil’s role in making gasoline. The polysilicon is then drawn out into a vast crystal, resembling a Jeff Koons steel sculpture of a sausage, before being sliced into salami-thin wafers. These are then treated, printed with electrodes, and finally sandwiched between glass. Marcella Townsend remembers looking around the kitchen in shock. In the silence just after the explosion, before the pain kicked in, she found herself almost in awe of the crushed stove and the caved-in cabinets.

Marcella Townsend remembers looking around the kitchen in shock. In the silence just after the explosion, before the pain kicked in, she found herself almost in awe of the crushed stove and the caved-in cabinets. Latest estimates indicate that the number of patients affected by cancer will increase dramatically through the middle of the century across all regions of the world. At the same time, the innovation ecosystem that discovers, develops, and delivers breakthrough therapies in entire new areas of science is operating near peak levels. Rising incidence, increasing numbers of treated patients, and the resulting expected growth in spending in this area will trigger an array of complex challenges over the next several years that are reflected in the trends highlighted in this report.

Latest estimates indicate that the number of patients affected by cancer will increase dramatically through the middle of the century across all regions of the world. At the same time, the innovation ecosystem that discovers, develops, and delivers breakthrough therapies in entire new areas of science is operating near peak levels. Rising incidence, increasing numbers of treated patients, and the resulting expected growth in spending in this area will trigger an array of complex challenges over the next several years that are reflected in the trends highlighted in this report. You only meet a few people in your life who, like stars, exert a pull so strong that they alter its trajectory completely. I was lucky enough to enter the orbit of the legendary editor and essayist Lewis Lapham. A week ago, I attended his memorial service. He

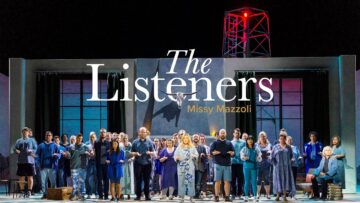

You only meet a few people in your life who, like stars, exert a pull so strong that they alter its trajectory completely. I was lucky enough to enter the orbit of the legendary editor and essayist Lewis Lapham. A week ago, I attended his memorial service. He  Claire Devon, the protagonist of Missy Mazzoli’s seductively nightmarish opera “The Listeners,” is living contentedly as a suburban schoolteacher somewhere in the Southwest when she is beset by an inexplicable, inescapable sound. It is described as a “dull hum,” an “aggressive drone,” which renders daily existence intolerable. As she searches for the source of the noise, her life unravels by degrees. She develops an ill-defined, ill-fated attachment to one of her students, who also hears the hum. Her husband and her daughter move out; the school fires her. She falls in with a psychiatrist, Howard Bard, who presides over a cultish association of Listeners—people attuned to the hum. When one of them, a conspiracy theorist, fires a gun at a cell tower, the police spring into action and violence ensues. The ending is as unexpected as it is unsettling. Instead of fleeing the cult, Claire takes control of it, the hum having awakened charismatic powers within her. “We all need a family that understands us,” she intones, as Listeners crowd around her.

Claire Devon, the protagonist of Missy Mazzoli’s seductively nightmarish opera “The Listeners,” is living contentedly as a suburban schoolteacher somewhere in the Southwest when she is beset by an inexplicable, inescapable sound. It is described as a “dull hum,” an “aggressive drone,” which renders daily existence intolerable. As she searches for the source of the noise, her life unravels by degrees. She develops an ill-defined, ill-fated attachment to one of her students, who also hears the hum. Her husband and her daughter move out; the school fires her. She falls in with a psychiatrist, Howard Bard, who presides over a cultish association of Listeners—people attuned to the hum. When one of them, a conspiracy theorist, fires a gun at a cell tower, the police spring into action and violence ensues. The ending is as unexpected as it is unsettling. Instead of fleeing the cult, Claire takes control of it, the hum having awakened charismatic powers within her. “We all need a family that understands us,” she intones, as Listeners crowd around her. The 2024 Nobel Prize in physics has been awarded to John Hopfield and Geoffrey Hinton for their “foundational discoveries” that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks.

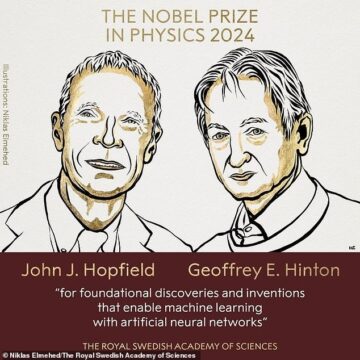

The 2024 Nobel Prize in physics has been awarded to John Hopfield and Geoffrey Hinton for their “foundational discoveries” that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks. Abrupt policy-inspired breakups are just one socio-ethical dilemma ushered in by the era of artificial intimacy. What are the psychological effects of spending time with AI-powered companions that provide everything from fictionalized character building to sexually explicit role play to recreating old-school girlfriends and boyfriends who promise to never ghost or dump you?

Abrupt policy-inspired breakups are just one socio-ethical dilemma ushered in by the era of artificial intimacy. What are the psychological effects of spending time with AI-powered companions that provide everything from fictionalized character building to sexually explicit role play to recreating old-school girlfriends and boyfriends who promise to never ghost or dump you? How do you prove something is true? For mathematicians, the answer is simple: Start with some basic assumptions and proceed, step by step, to the conclusion. QED, proof complete. If there’s a mistake anywhere, an expert who reads the proof carefully should be able to spot it. Otherwise, the proof must be valid. Mathematicians have been following this basic approach for well over 2,000 years.

How do you prove something is true? For mathematicians, the answer is simple: Start with some basic assumptions and proceed, step by step, to the conclusion. QED, proof complete. If there’s a mistake anywhere, an expert who reads the proof carefully should be able to spot it. Otherwise, the proof must be valid. Mathematicians have been following this basic approach for well over 2,000 years. The press and especially the news channels are constantly warning us that antisemitism is everywhere on the rise. They don’t point to specific episodes, content instead to denounce an ancient prejudice that in the context of a Middle East crisis is staging a resurgence. No, they describe a gigantic wave of antisemitism that has been sweeping across the globe since October 7. Its epicenter is on American college campuses, just as the epicenter of the anti–Vietnam War movement was on college campuses sixty years ago.

The press and especially the news channels are constantly warning us that antisemitism is everywhere on the rise. They don’t point to specific episodes, content instead to denounce an ancient prejudice that in the context of a Middle East crisis is staging a resurgence. No, they describe a gigantic wave of antisemitism that has been sweeping across the globe since October 7. Its epicenter is on American college campuses, just as the epicenter of the anti–Vietnam War movement was on college campuses sixty years ago. At a time of widespread economic distress, ethnonationalists in the United States and United Kingdom as well as Germany, France, Hungary, Poland and Italy are united by their antipathy to immigrants, and targeting of institutions deemed insufficiently patriotic or indulgent of sexual, ethnic and racial minorities. This bleak scenario can be further elaborated. The main economic ideologies of endless growth and global prosperity have come up against environmental constraints and technological innovation, as well as built-in limits, and look unsustainable.

At a time of widespread economic distress, ethnonationalists in the United States and United Kingdom as well as Germany, France, Hungary, Poland and Italy are united by their antipathy to immigrants, and targeting of institutions deemed insufficiently patriotic or indulgent of sexual, ethnic and racial minorities. This bleak scenario can be further elaborated. The main economic ideologies of endless growth and global prosperity have come up against environmental constraints and technological innovation, as well as built-in limits, and look unsustainable. Like her other works—including Sister Deborah, the English translation of which is forthcoming from Archipelago later this month—Cockroaches is a reckoning with history, a steadfast commemoration of a community and culture that others tried to eradicate. But even in her debut, which many early critics read as a straightforward work of testimony about the Tutsi genocide, there is a deeply self-questioning quality to that work of commemoration. The narrator always wakes from her nightmare just as she is about to perish at the hands of her pursuers, who have already killed the other Tutsi girls fleeing alongside her. She thinks, “I know I’m going to fall, I’m going to be trampled”; and yet each night she reopens her eyes and her surroundings contradict this conviction. Why was she chosen to survive, and who did the choosing?

Like her other works—including Sister Deborah, the English translation of which is forthcoming from Archipelago later this month—Cockroaches is a reckoning with history, a steadfast commemoration of a community and culture that others tried to eradicate. But even in her debut, which many early critics read as a straightforward work of testimony about the Tutsi genocide, there is a deeply self-questioning quality to that work of commemoration. The narrator always wakes from her nightmare just as she is about to perish at the hands of her pursuers, who have already killed the other Tutsi girls fleeing alongside her. She thinks, “I know I’m going to fall, I’m going to be trampled”; and yet each night she reopens her eyes and her surroundings contradict this conviction. Why was she chosen to survive, and who did the choosing?