David Mason at The Hudson Review:

For Christmas lunch, 1937, Virginia and Leonard Woolf hosted John Maynard Keynes and his wife, Lydia. Imagine the talk, which no doubt ranged widely, including gossip about younger writers like W. H. Auden, the recipient that autumn of the King’s Gold Medal for Poetry from George VI himself. A lot of people were saying it: Auden was the man to watch. At only thirty, he was already regarded as England’s leading poet, head of a squadron of younger writers, including Louis MacNeice, C. Day-Lewis and Stephen Spender. According to Nicholas Jenkins’ important new book, The Island: War and Belonging in Auden’s England,[1] Keynes was “offended by Auden’s standards of personal hygiene,” telling the Woolfs that the poet was “very dirty but a genius.”

For Christmas lunch, 1937, Virginia and Leonard Woolf hosted John Maynard Keynes and his wife, Lydia. Imagine the talk, which no doubt ranged widely, including gossip about younger writers like W. H. Auden, the recipient that autumn of the King’s Gold Medal for Poetry from George VI himself. A lot of people were saying it: Auden was the man to watch. At only thirty, he was already regarded as England’s leading poet, head of a squadron of younger writers, including Louis MacNeice, C. Day-Lewis and Stephen Spender. According to Nicholas Jenkins’ important new book, The Island: War and Belonging in Auden’s England,[1] Keynes was “offended by Auden’s standards of personal hygiene,” telling the Woolfs that the poet was “very dirty but a genius.”

We rarely associate Auden’s poetry with the slovenly and remember his tidy stanzas too often as something cold and oblique, iceberg verse. His early work has been published as The English Auden (1977), appearing to emphasize the national (even nationalist) poet, a thoroughly domesticated animal. As Jenkins argues in over 500 densely written pages, there is a lot of truth in this image.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

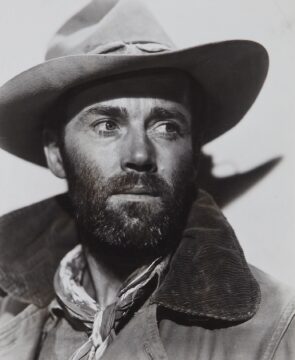

THERE’S A REASON why so many people regard Ronald Reagan as America’s last great leader. The further the monolithic Hollywood of the storied past recedes into the fragmented fun house of the media present, the more mythic the stellar avatars appear. One such divinity: straight-talking, honorable, unassuming, heroic Henry Fonda (1905–1982).

THERE’S A REASON why so many people regard Ronald Reagan as America’s last great leader. The further the monolithic Hollywood of the storied past recedes into the fragmented fun house of the media present, the more mythic the stellar avatars appear. One such divinity: straight-talking, honorable, unassuming, heroic Henry Fonda (1905–1982). How does the brain

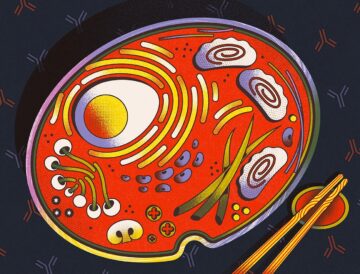

How does the brain Reboot your immune system with intermittent fasting. Help your ‘good’ bacteria to thrive with a plant-based diet. Move over morning coffee: mushroom tea could bolster your anticancer defences. Claims such as these, linking health, diet and immunity, bombard supermarket shoppers and pervade the news. Beyond the headlines and product labels, the scientific foundations of many such claims are often based on limited evidence. That’s partly because conducting rigorous studies to track what people eat and the impact of diet

Reboot your immune system with intermittent fasting. Help your ‘good’ bacteria to thrive with a plant-based diet. Move over morning coffee: mushroom tea could bolster your anticancer defences. Claims such as these, linking health, diet and immunity, bombard supermarket shoppers and pervade the news. Beyond the headlines and product labels, the scientific foundations of many such claims are often based on limited evidence. That’s partly because conducting rigorous studies to track what people eat and the impact of diet  The car I bought in Hamburg had distinctive oval German export license plates, and an international registration sticker marked with a D, for Deutschland. As I drove through Holland on my way to Paris, more than once when asking for directions I received dirty looks, especially from older persons for whom the wartime German occupation was a living memory.

The car I bought in Hamburg had distinctive oval German export license plates, and an international registration sticker marked with a D, for Deutschland. As I drove through Holland on my way to Paris, more than once when asking for directions I received dirty looks, especially from older persons for whom the wartime German occupation was a living memory. In The Oxford Book of Modern Science Writing (2008), Richard Dawkins writes:

In The Oxford Book of Modern Science Writing (2008), Richard Dawkins writes: Why are some countries richer than others? The 2024 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel has been awarded to three researchers who have helped shed light on this fundamental question.

Why are some countries richer than others? The 2024 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel has been awarded to three researchers who have helped shed light on this fundamental question. J

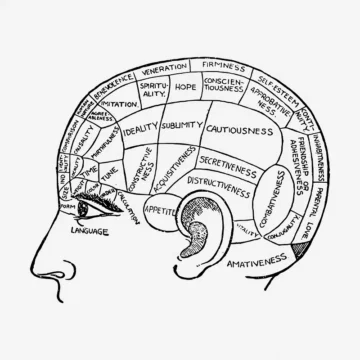

J Foucault was greatly disturbed by modern psychiatry’s ability to draw definitive lines between the ‘reasonable’ and the ‘unreasonable’. He came to see it as another way for society to punish and marginalise its most troublesome subjects. Deploying the metaphor of a circulatory system, he conceived of psychiatrists as figures of ‘capillary’ power – unlike the conspicuous, beating heart of the state, these authorities functioned as more subtle, distal agents of the status quo. Writing in the 1960s and ’70s, Foucault saw the psychoanalytic therapists of his day as the latest technicians managing ‘one of the West’s most highly valued techniques for producing truth of one kind or another’ – the confession. This is the idea that disclosing one’s inner darkness leads to salvation, truth, self-actualisation. There is an important similarity between how this dynamic plays out in the church and the clinic: ‘bravely confront and share the ugly things inside you’ equally describes the task of the confessional booth as it does the therapist’s couch. In both cases, there is more at play here than simple unburdening: it is not just that ‘shared sorrow is half sorrow’, as in the case of confiding in a friend, but also that having an adversarial encounter with yourself can be fruitful in some way.

Foucault was greatly disturbed by modern psychiatry’s ability to draw definitive lines between the ‘reasonable’ and the ‘unreasonable’. He came to see it as another way for society to punish and marginalise its most troublesome subjects. Deploying the metaphor of a circulatory system, he conceived of psychiatrists as figures of ‘capillary’ power – unlike the conspicuous, beating heart of the state, these authorities functioned as more subtle, distal agents of the status quo. Writing in the 1960s and ’70s, Foucault saw the psychoanalytic therapists of his day as the latest technicians managing ‘one of the West’s most highly valued techniques for producing truth of one kind or another’ – the confession. This is the idea that disclosing one’s inner darkness leads to salvation, truth, self-actualisation. There is an important similarity between how this dynamic plays out in the church and the clinic: ‘bravely confront and share the ugly things inside you’ equally describes the task of the confessional booth as it does the therapist’s couch. In both cases, there is more at play here than simple unburdening: it is not just that ‘shared sorrow is half sorrow’, as in the case of confiding in a friend, but also that having an adversarial encounter with yourself can be fruitful in some way. Representing suffering—how to do it, when we should do it at all—has long been a subject of debate. At the center of that debate is the role of the audience: how do we, as readers and viewers, witness depictions of violence in images, films, plays, or literature?

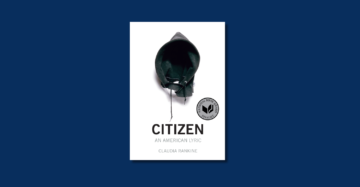

Representing suffering—how to do it, when we should do it at all—has long been a subject of debate. At the center of that debate is the role of the audience: how do we, as readers and viewers, witness depictions of violence in images, films, plays, or literature? The Swedish Academy is not here to tell you what writers you might like. Greatness is not the same as popularity. It may even be the opposite of popularity. Great books are by definition not the books you read for pleasure — even if some of them turn out to be, and may even have been intended to be, fun — and great writers, being mostly dead, don’t care if they’re your favorites. The great books are the ones you’re supposed to feel bad about not having read. Great writers are the ones who matter whether you read them or not.

The Swedish Academy is not here to tell you what writers you might like. Greatness is not the same as popularity. It may even be the opposite of popularity. Great books are by definition not the books you read for pleasure — even if some of them turn out to be, and may even have been intended to be, fun — and great writers, being mostly dead, don’t care if they’re your favorites. The great books are the ones you’re supposed to feel bad about not having read. Great writers are the ones who matter whether you read them or not.

The U.S. presidential election is decided by American citizens in a handful of states, but its outcome reverberates internationally: the new president will have the power to shape trade, migration, security and rising authoritarianism across the world, as well as the wars in Gaza and Ukraine. The race is therefore a global event, the subject of countless newspaper articles, debates and calculations. We asked 12 writers, each from a different country, to share what the conversation sounds like where they live: What are politicians saying, and how is the press covering the race? What are the hopes for a Kamala Harris presidency, or a Donald Trump one — and what are the fears? Our writers describe widely divergent attitudes toward the election and its unknown conclusion, from apathy and disillusionment to anxiety, hope and glee.

The U.S. presidential election is decided by American citizens in a handful of states, but its outcome reverberates internationally: the new president will have the power to shape trade, migration, security and rising authoritarianism across the world, as well as the wars in Gaza and Ukraine. The race is therefore a global event, the subject of countless newspaper articles, debates and calculations. We asked 12 writers, each from a different country, to share what the conversation sounds like where they live: What are politicians saying, and how is the press covering the race? What are the hopes for a Kamala Harris presidency, or a Donald Trump one — and what are the fears? Our writers describe widely divergent attitudes toward the election and its unknown conclusion, from apathy and disillusionment to anxiety, hope and glee.