Seyla Benhabib in Boston Review:

I first arrived in Frankfurt, in this city of immigrants and exiles, in the fall of 1980, as a foreign student and scholar whose life was forever changed by her encounter with it. In Frankfurt I met brilliant friends and scholars from all over the world who gathered in Jürgen Habermas’s “Doktoranden-Kolloquium” on Monday evenings in the old Department of Philosophy on Dantestrasse—alas, a building which no longer exists! In Frankfurt, I also learned about many famous intellectuals whose lives intersected for various periods in this city of migrants, among them none other than Hannah Arendt and Theodor Adorno.

Any consideration of Arendt and Adorno as thinkers who share intellectual affinities is likely to be thwarted from the start by the profound dislike which Arendt in particular seems to have borne towards Adorno. In 1929 Adorno was among members of the faculty of the University of Frankfurt who would be evaluating Arendt’s first husband Günther Anders’s habilitation. Adorno found the work unsatisfactory, thus bringing to an end Anders’s hopes for a university career. It is also in this period that Arendt’s notorious statement regarding Adorno—“Der kommt uns nicht ins Haus,” meaning that Adorno was not to set foot in their apartment in Frankfurt—was uttered.

This hostility on Arendt’s part never diminished, while Adorno encountered it with a cultivated politesse. Arendt’s temper flared up several more times at Adorno: first, when she was wrongly convinced that Adorno and his colleagues were preventing the publication of Walter Benjamin’s posthumous manuscripts, and secondly, when Adorno’s critique of Heidegger—The Jargon of Authenticity—appeared in 1964.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Across 15,000 generations, human beings have looked out at the sentinel stars and felt the pressing weight of myriad existential questions: Are we alone? Are there other planets also orbiting distant suns? If so, have any of these other worlds also birthed life, or is the drama of our Earth a singular cosmic accident? And what about other minds and civilizations? Have others in the universe, through their success as tool-builders and world-makers, also brought themselves to the brink of collapse?

Across 15,000 generations, human beings have looked out at the sentinel stars and felt the pressing weight of myriad existential questions: Are we alone? Are there other planets also orbiting distant suns? If so, have any of these other worlds also birthed life, or is the drama of our Earth a singular cosmic accident? And what about other minds and civilizations? Have others in the universe, through their success as tool-builders and world-makers, also brought themselves to the brink of collapse? In Amrith’s view, all history is environmental history. And that includes both environmental effects on societies and those societies’ impacts on the environment. He cites evidence, for example, suggesting that a “medieval warm period” spanned most of Europe and parts of North America and western Asia through the 13th century. The period’s benign climate and rainfall, he argues, allowed societies to clear land, expand cultivation, build cities, and grow their populations. He also assesses the rise and fall of the Mongols, who swept across Asia quickly before being thwarted by limited grasses for their horses, intense snowstorms and earthquakes, and deadly plagues that the Mongolian expansion helped spread.

In Amrith’s view, all history is environmental history. And that includes both environmental effects on societies and those societies’ impacts on the environment. He cites evidence, for example, suggesting that a “medieval warm period” spanned most of Europe and parts of North America and western Asia through the 13th century. The period’s benign climate and rainfall, he argues, allowed societies to clear land, expand cultivation, build cities, and grow their populations. He also assesses the rise and fall of the Mongols, who swept across Asia quickly before being thwarted by limited grasses for their horses, intense snowstorms and earthquakes, and deadly plagues that the Mongolian expansion helped spread. I think of an essay as a realm for both the writer and the reader. When I’m working on an essay, I’m entering a loosely defined space. If we borrow Alexander’s terms again, the essay in progress is “the site”: “It is essential to work on the site,” he writes, in A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; “Work on the site, stay on the site, let the site tell you its secrets.” Just by beginning to think about an essay as such—by forming the intention to write on an idea or theme—I’m opening a portal, I’m creating a site, a realm. It’s a place where all my best thinking can go for a period of time, a place where the thoughts can be collected and arranged for more density of meaning. This place necessarily has structure, if it feels like a place. There’s a classic architecture book called Why Buildings Stand Up. We call any building, or part of a building, or thing like a building, a structure, if it succeeds in standing up. The structure is the system of elements in the building that make things go up—the load-bearing elements, walls and beams and columns, that counteract gravity. They counteract quote-unquote nothing, so empty space becomes a place.

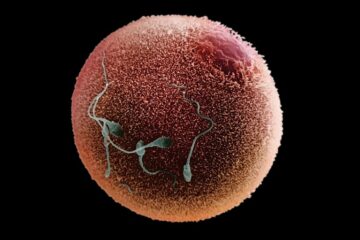

I think of an essay as a realm for both the writer and the reader. When I’m working on an essay, I’m entering a loosely defined space. If we borrow Alexander’s terms again, the essay in progress is “the site”: “It is essential to work on the site,” he writes, in A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; “Work on the site, stay on the site, let the site tell you its secrets.” Just by beginning to think about an essay as such—by forming the intention to write on an idea or theme—I’m opening a portal, I’m creating a site, a realm. It’s a place where all my best thinking can go for a period of time, a place where the thoughts can be collected and arranged for more density of meaning. This place necessarily has structure, if it feels like a place. There’s a classic architecture book called Why Buildings Stand Up. We call any building, or part of a building, or thing like a building, a structure, if it succeeds in standing up. The structure is the system of elements in the building that make things go up—the load-bearing elements, walls and beams and columns, that counteract gravity. They counteract quote-unquote nothing, so empty space becomes a place. Recently, a team at Stanford University fished something new out of the vast, uncharted, and almost entirely unclassified world of genetic material sometimes known as biological dark matter. They called it an “obelisk,” a shell-less RNA of maybe 1,000 base pairs (shorter than any viral genome), which seems to self-organize into a rodlike shape. It appears to be the structural equivalent of a plant viroid or a fungal ambivirus, two other bits of self-replicating genetic material whose discovery widened the boundaries of what we know about microbiology. But the obelisks weren’t found in either plants or fungi. They were discovered in human intestines.

Recently, a team at Stanford University fished something new out of the vast, uncharted, and almost entirely unclassified world of genetic material sometimes known as biological dark matter. They called it an “obelisk,” a shell-less RNA of maybe 1,000 base pairs (shorter than any viral genome), which seems to self-organize into a rodlike shape. It appears to be the structural equivalent of a plant viroid or a fungal ambivirus, two other bits of self-replicating genetic material whose discovery widened the boundaries of what we know about microbiology. But the obelisks weren’t found in either plants or fungi. They were discovered in human intestines. Interest in

Interest in  O

O I grew up on the north side of Chicago in a pretty diverse school district that had students with backgrounds hailing from all corners of the world. I remember hearing a classmate speak to his mom in Polish when she picked him up. Another classmate brought Pakistani Biryani his mom made for lunch. It was a quite riveting experience at a young age to have exposure to such a vibrant student body. Everyone had a story, a history, a culture, yet we were all American kids raised on a steady diet of pop culture and pop tarts. Nonetheless, these kids’ subtle yet unique cultural undertones first sparked my curiosity to know more about the world.

I grew up on the north side of Chicago in a pretty diverse school district that had students with backgrounds hailing from all corners of the world. I remember hearing a classmate speak to his mom in Polish when she picked him up. Another classmate brought Pakistani Biryani his mom made for lunch. It was a quite riveting experience at a young age to have exposure to such a vibrant student body. Everyone had a story, a history, a culture, yet we were all American kids raised on a steady diet of pop culture and pop tarts. Nonetheless, these kids’ subtle yet unique cultural undertones first sparked my curiosity to know more about the world. An artificial-intelligence tool honoured by this year’s Nobel prize

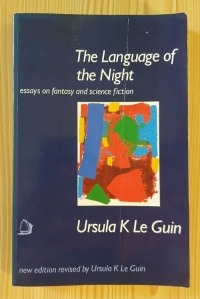

An artificial-intelligence tool honoured by this year’s Nobel prize In ‘Dreams Must Explain Themselves’ (1973), Le Guin touches on the reference works that she consults for her writing (I’m a

In ‘Dreams Must Explain Themselves’ (1973), Le Guin touches on the reference works that she consults for her writing (I’m a