Cynthia Haven at the Book Haven:

Interest in René Girard from an unexpected source: the current issue of Air Mail, which describes itself as a “mobile-first digital weekly that unfolds like the better weekend editions of your favorite newspapers.” Dramatist, novelist, and poet Matthew Gasda writes: “We are all Girardians now—whether we know it or not. The concepts minted in the early 1960s by the late French literary critic and philosopher René Girard explain the pathologies of the smartphone age as elegantly as Freud’s explained bourgeois neuroses at the turn of the last century.”

Interest in René Girard from an unexpected source: the current issue of Air Mail, which describes itself as a “mobile-first digital weekly that unfolds like the better weekend editions of your favorite newspapers.” Dramatist, novelist, and poet Matthew Gasda writes: “We are all Girardians now—whether we know it or not. The concepts minted in the early 1960s by the late French literary critic and philosopher René Girard explain the pathologies of the smartphone age as elegantly as Freud’s explained bourgeois neuroses at the turn of the last century.”

Gaspa is a voice worth listening to. Two years ago, the New York Times noted: “Matthew Gasda spent years writing plays on his electric typewriter, and almost no one seemed to care. With Dimes Square, his depiction of a downtown crowd, he has an underground hit.” And so he’s been a voice worth listening to ever since.

Which is especially good for All Desire is a Desire for Being, just out with Penguin Classics U.S. (The U.K. edition was published last year.) You can buy the book here. Meanwhile, read Gasda’s review of the book.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

O

O I grew up on the north side of Chicago in a pretty diverse school district that had students with backgrounds hailing from all corners of the world. I remember hearing a classmate speak to his mom in Polish when she picked him up. Another classmate brought Pakistani Biryani his mom made for lunch. It was a quite riveting experience at a young age to have exposure to such a vibrant student body. Everyone had a story, a history, a culture, yet we were all American kids raised on a steady diet of pop culture and pop tarts. Nonetheless, these kids’ subtle yet unique cultural undertones first sparked my curiosity to know more about the world.

I grew up on the north side of Chicago in a pretty diverse school district that had students with backgrounds hailing from all corners of the world. I remember hearing a classmate speak to his mom in Polish when she picked him up. Another classmate brought Pakistani Biryani his mom made for lunch. It was a quite riveting experience at a young age to have exposure to such a vibrant student body. Everyone had a story, a history, a culture, yet we were all American kids raised on a steady diet of pop culture and pop tarts. Nonetheless, these kids’ subtle yet unique cultural undertones first sparked my curiosity to know more about the world. An artificial-intelligence tool honoured by this year’s Nobel prize

An artificial-intelligence tool honoured by this year’s Nobel prize In ‘Dreams Must Explain Themselves’ (1973), Le Guin touches on the reference works that she consults for her writing (I’m a

In ‘Dreams Must Explain Themselves’ (1973), Le Guin touches on the reference works that she consults for her writing (I’m a

I

I  But if there was little obvious distinction between “religious” pilgrims and “regular” travelers, it was partly because the discourse of contemporary travel is so often geared toward the same ends as pilgrimage proper: a journey that results in the transformation, and ideally purification, of the searching self. This is the goal underlying, for example, travel-as-transformation narratives like Cheryl Strayed’s Wild, an account of the author’s solo hike along the Pacific Crest Trail, and Elizabeth Gilbert’s divorce-and-self-actualization memoir Eat, Pray, Love. Travel, at least the kind of travel so often coded as “real” or “authentic” (as opposed to, say, the family resort vacation, the Instagram trip, or the perfunctory list-ticking of the much-derided “tourist”), is already treated as a kind of secular pilgrimage in which we find out who we really are only by untethering ourselves from those elements of our identities too closely linked to habit and home. Only when we are away from our daily routines, this ideology implies, from our bosses and spouses and children, when we are challenged by language barrier or public transit mishap or unexpected romantic chemistry, can we come to know who we really are.

But if there was little obvious distinction between “religious” pilgrims and “regular” travelers, it was partly because the discourse of contemporary travel is so often geared toward the same ends as pilgrimage proper: a journey that results in the transformation, and ideally purification, of the searching self. This is the goal underlying, for example, travel-as-transformation narratives like Cheryl Strayed’s Wild, an account of the author’s solo hike along the Pacific Crest Trail, and Elizabeth Gilbert’s divorce-and-self-actualization memoir Eat, Pray, Love. Travel, at least the kind of travel so often coded as “real” or “authentic” (as opposed to, say, the family resort vacation, the Instagram trip, or the perfunctory list-ticking of the much-derided “tourist”), is already treated as a kind of secular pilgrimage in which we find out who we really are only by untethering ourselves from those elements of our identities too closely linked to habit and home. Only when we are away from our daily routines, this ideology implies, from our bosses and spouses and children, when we are challenged by language barrier or public transit mishap or unexpected romantic chemistry, can we come to know who we really are. T

T Human life expectancy dramatically increased last century. Compared to babies born in 1900, those born at the turn of the 21st century could live, on average, three decades longer—

Human life expectancy dramatically increased last century. Compared to babies born in 1900, those born at the turn of the 21st century could live, on average, three decades longer— It is midday on a Friday, and I am in a room with about a dozen teenagers at an international school in Oslo, Norway. We are talking about how and why they use TikTok, the digital video-sharing application. The prevailing mood is laid-back: though I am technically a media researcher, and they are technically my research participants, this group of 16- and 17-year-olds are joking around with each other and with me as we chat about the role of TikTok in their everyday lives. It’s a beautiful day – warm and summery – and everyone, including me, is in a fun weekend mood.

It is midday on a Friday, and I am in a room with about a dozen teenagers at an international school in Oslo, Norway. We are talking about how and why they use TikTok, the digital video-sharing application. The prevailing mood is laid-back: though I am technically a media researcher, and they are technically my research participants, this group of 16- and 17-year-olds are joking around with each other and with me as we chat about the role of TikTok in their everyday lives. It’s a beautiful day – warm and summery – and everyone, including me, is in a fun weekend mood. Terence Tao snorts and waves his hands dismissively when he hears that he is the most intelligent human being on the planet, according to a number of online rankings, including a recent one conducted by the

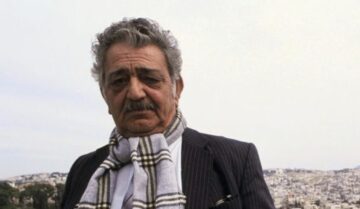

Terence Tao snorts and waves his hands dismissively when he hears that he is the most intelligent human being on the planet, according to a number of online rankings, including a recent one conducted by the  The Palestinian Nakba produced, alongside death and displacement, a generation of writers who came of age in its aftermath. The moment seemed to demand a funereal tone from artists who had witnessed the tragedy. For them, a version of Theodor Adorno’s maxim, that to “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” rung true. Few broke the taboo.

The Palestinian Nakba produced, alongside death and displacement, a generation of writers who came of age in its aftermath. The moment seemed to demand a funereal tone from artists who had witnessed the tragedy. For them, a version of Theodor Adorno’s maxim, that to “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” rung true. Few broke the taboo.

It’s not immoral to kick a rock; it is immoral to kick a baby. At what point do we start saying that it is wrong to cause pain to something? This question has less to do with “consciousness” and more to do with “sentience” — the ability to perceive feelings and sensations. Philosopher Jonathan Birch has embarked on a careful study of the meaning of sentience and how it can be identified in different kinds of organisms, as he discusses in his new open-access book

It’s not immoral to kick a rock; it is immoral to kick a baby. At what point do we start saying that it is wrong to cause pain to something? This question has less to do with “consciousness” and more to do with “sentience” — the ability to perceive feelings and sensations. Philosopher Jonathan Birch has embarked on a careful study of the meaning of sentience and how it can be identified in different kinds of organisms, as he discusses in his new open-access book