Erin McMullen in Time Magazine:

Padma Lakshmi, a fixture of American culinary television since the early aughts, knows that many people are used to hearing her speak in one language: food. So when she felt called to action in the wake of the 2016 election, frustrated by anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies, she channeled her desire for change into a new TV show—one that highlighted the cuisines of immigrant and Indigenous communities across the U.S.

Padma Lakshmi, a fixture of American culinary television since the early aughts, knows that many people are used to hearing her speak in one language: food. So when she felt called to action in the wake of the 2016 election, frustrated by anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies, she channeled her desire for change into a new TV show—one that highlighted the cuisines of immigrant and Indigenous communities across the U.S.

Taste the Nation, a Hulu docu-series that premiered in 2020, followed Lakshmi—an immigrant herself, having moved to the U.S. from India as a child—as she traversed the country in an effort to learn more about the cultures that have shaped American food for decades. The aptly-named series saw the former host of Top Chef sample Mexican cuisine in Texas, Thai dishes in Nevada, and Greek eats in Florida. It was her “Trojan horse,” a show that used food as a way to make people curious about America, its people, and its history.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

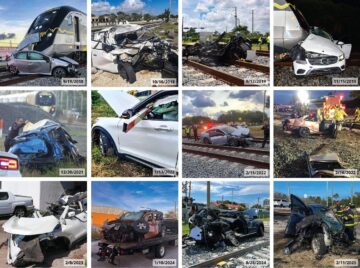

Brightline is the nation’s most dangerous passenger train, reporters found, killing someone every 13 days of service, on average. In addition to those deaths, 99 people have been injured. In at least 101 cases, the train crashed into vehicles, but no one was hurt.

Brightline is the nation’s most dangerous passenger train, reporters found, killing someone every 13 days of service, on average. In addition to those deaths, 99 people have been injured. In at least 101 cases, the train crashed into vehicles, but no one was hurt. Authorities are scrambling to provide drinking water across Iran, particularly in the capital, Tehran, as Iranians grapple with the

Authorities are scrambling to provide drinking water across Iran, particularly in the capital, Tehran, as Iranians grapple with the  The yearly Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change—COP, to habitués—has morphed, over the years, into a kind of travelling circus grotesquely mismatched to the problem it’s meant to address.

The yearly Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change—COP, to habitués—has morphed, over the years, into a kind of travelling circus grotesquely mismatched to the problem it’s meant to address. Everyone agrees that modern poetry in France—and therefore in Europe—starts with Charles Baudelaire. But no one agrees on why. His successors, Arthur Rimbaud and Stéphane Mallarmé, are each in their own way more patently radical, and the same is true of his American contemporary Walt Whitman. How modern do you have to be to be a modern? Compared to their works, those of Baudelaire, despite their sulfurous aroma, are far more traditional; while he was an early adopter of the prose poem, his most influential poetry used received forms. “Baudelaire accomplished what classical prosody had always required, or rather what it had inaugurated. … His prosody has the same spiritual monotony as Racine’s,” Yves Bonnefoy once remarked. And beyond matters of form, some of Baudelaire’s content was familiar too. His exacerbated ambivalence toward his Haitian-born lover Jeanne Duval, the subject of so many of his poems, is as ancient as Catullus’s odi et amo; praise of drunkenness dates back to the Greeks; and his proud sense of damnation, of his “Heart great with rancor and bitter desires,” would have been second-hand news to Lord Byron. Was the “new shudder” that Victor Hugo perceived in Baudelaire’s writing new enough to make him, rather than the last of the Romantics (the one in whose work Romanticism, you might say, curdled), the first of the moderns?

Everyone agrees that modern poetry in France—and therefore in Europe—starts with Charles Baudelaire. But no one agrees on why. His successors, Arthur Rimbaud and Stéphane Mallarmé, are each in their own way more patently radical, and the same is true of his American contemporary Walt Whitman. How modern do you have to be to be a modern? Compared to their works, those of Baudelaire, despite their sulfurous aroma, are far more traditional; while he was an early adopter of the prose poem, his most influential poetry used received forms. “Baudelaire accomplished what classical prosody had always required, or rather what it had inaugurated. … His prosody has the same spiritual monotony as Racine’s,” Yves Bonnefoy once remarked. And beyond matters of form, some of Baudelaire’s content was familiar too. His exacerbated ambivalence toward his Haitian-born lover Jeanne Duval, the subject of so many of his poems, is as ancient as Catullus’s odi et amo; praise of drunkenness dates back to the Greeks; and his proud sense of damnation, of his “Heart great with rancor and bitter desires,” would have been second-hand news to Lord Byron. Was the “new shudder” that Victor Hugo perceived in Baudelaire’s writing new enough to make him, rather than the last of the Romantics (the one in whose work Romanticism, you might say, curdled), the first of the moderns? Somehow I keep coming back to Nicholas of Cusa, that late medieval Renaissance man (1401-1464), a devout church leader and mathematical mystic who was at the same time one of the founders of modern experimental science—propagator, for example, of some of the first formal experiments in biology (proving that trees somehow absorb nourishment from the air, and that air, for that matter, has weight) and advocate, among other things, of the notion that the earth, far from being the center of the universe, might itself be in motion around the sun (this a good two generations before Copernicus), and yet, for all that, a cautionary skeptic as to the limits of that kind of quantifiable knowledge and thus, likewise, a critic of the then-reigning Aristotelian/Thomistic worldview. No, he would regularly insist, one could never achieve knowledge of God, or, for that matter, of the wholeness of existence, through the systematic accretion of more and more factual knowledge. Picture, he would suggest, an n-sided equilateral polygon nested inside a circle, and now keep adding to the number of its sides: triangle, square, pentagon, hexagon, and so forth. The more sides you added, the closer it might seem that you were getting to the bounding circle—and yet, he insisted, in another sense, the farther away you would in fact be getting. Because a million-sided regular polygon, say, has, precisely, a million sides and a million angles, whereas a circle has none, or maybe at most one.

Somehow I keep coming back to Nicholas of Cusa, that late medieval Renaissance man (1401-1464), a devout church leader and mathematical mystic who was at the same time one of the founders of modern experimental science—propagator, for example, of some of the first formal experiments in biology (proving that trees somehow absorb nourishment from the air, and that air, for that matter, has weight) and advocate, among other things, of the notion that the earth, far from being the center of the universe, might itself be in motion around the sun (this a good two generations before Copernicus), and yet, for all that, a cautionary skeptic as to the limits of that kind of quantifiable knowledge and thus, likewise, a critic of the then-reigning Aristotelian/Thomistic worldview. No, he would regularly insist, one could never achieve knowledge of God, or, for that matter, of the wholeness of existence, through the systematic accretion of more and more factual knowledge. Picture, he would suggest, an n-sided equilateral polygon nested inside a circle, and now keep adding to the number of its sides: triangle, square, pentagon, hexagon, and so forth. The more sides you added, the closer it might seem that you were getting to the bounding circle—and yet, he insisted, in another sense, the farther away you would in fact be getting. Because a million-sided regular polygon, say, has, precisely, a million sides and a million angles, whereas a circle has none, or maybe at most one. On the sub-tropical Japanese islands of Okinawa, they have a saying: Live far enough away from your family so you’re not running into them every day, but close enough to take them a warm bowl of soup – on foot. Many of us during the past 18 months would have benefited from living within walking distance of our family. We’ve had to make do with Zoom calls instead – and the

On the sub-tropical Japanese islands of Okinawa, they have a saying: Live far enough away from your family so you’re not running into them every day, but close enough to take them a warm bowl of soup – on foot. Many of us during the past 18 months would have benefited from living within walking distance of our family. We’ve had to make do with Zoom calls instead – and the  Within the broader discipline of philosophy, there is a split between what is called “analytic philosophy” and what is called “continental philosophy.” The gulf between these two camps is wide, and the dispute between them extremely acrimonious, although it is hard to articulate precisely what the difference between the two is. Any proposed account of this distinction – analytic philosophers are like this, while continentals are like that – will inevitably result in very angry objections. For one thing, any proposed distinction will inevitably mischaracterize several paradigmatic continental or analytic philosophers. But more importantly, the person proposing the distinction is usually a partisan of one camp or the other, and they characterize the distinction in terms that are extremely flattering to their own side. “Analytic philosophers prize rigor and clarity,” says that analytic philosopher, “whereas continentals do not.” “Go fuck yourself,” the continental philosopher replies.

Within the broader discipline of philosophy, there is a split between what is called “analytic philosophy” and what is called “continental philosophy.” The gulf between these two camps is wide, and the dispute between them extremely acrimonious, although it is hard to articulate precisely what the difference between the two is. Any proposed account of this distinction – analytic philosophers are like this, while continentals are like that – will inevitably result in very angry objections. For one thing, any proposed distinction will inevitably mischaracterize several paradigmatic continental or analytic philosophers. But more importantly, the person proposing the distinction is usually a partisan of one camp or the other, and they characterize the distinction in terms that are extremely flattering to their own side. “Analytic philosophers prize rigor and clarity,” says that analytic philosopher, “whereas continentals do not.” “Go fuck yourself,” the continental philosopher replies. Rats have gotten a bad reputation over the years for being dirty,

Rats have gotten a bad reputation over the years for being dirty,

In 2004 the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben was scheduled to spend the spring semester as a visiting professor at NYU. On January 5 of that year, however, the Department of Homeland Security launched a new program to collect fingerprints from foreign visitors. Though EU citizens were exempted, three days later Agamben announced that “personally, I have no intention of submitting myself to such procedures,” and he refused to come to the US. In a statement first published in La Repubblica, he warned that collecting fingerprints marked a new “threshold in the control and manipulation of bodies”—what Michel Foucault had named “biopolitics.” Agamben described fingerprint collection as a perfect example of this tyranny over bodies and called it “biopolitical tattooing,” analogous to the tattooing of numbers on prisoners’ arms at Auschwitz.

In 2004 the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben was scheduled to spend the spring semester as a visiting professor at NYU. On January 5 of that year, however, the Department of Homeland Security launched a new program to collect fingerprints from foreign visitors. Though EU citizens were exempted, three days later Agamben announced that “personally, I have no intention of submitting myself to such procedures,” and he refused to come to the US. In a statement first published in La Repubblica, he warned that collecting fingerprints marked a new “threshold in the control and manipulation of bodies”—what Michel Foucault had named “biopolitics.” Agamben described fingerprint collection as a perfect example of this tyranny over bodies and called it “biopolitical tattooing,” analogous to the tattooing of numbers on prisoners’ arms at Auschwitz. When David Szalay’s novel “

When David Szalay’s novel “