Gregory Martin at The American Scholar:

Charlotte’s Web, however, is a perfect book, a masterpiece about living and dying well. There should be some universal magic spell that prevents a child from seeing any Charlotte’s Web movie before reading the book. Evan is 22 now, a college senior studying psychology and philosophy, but he has still not read Charlotte’s Web. I read aloud to him so many books when he was little and later, well into his elementary years. I loved this, and he loved this. I loved reading to him as much as anything I have loved. That I did not read Charlotte’s Web aloud to Evan has to be considered one of the real failures, among many, of my parenting career.

How else to do right by one’s favorite authors than to pass them on, read them aloud, urge them on the ones we love? On anyone who will listen?

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Neuroscientists have been studying more cognition-based questions — like how the brain recognizes patterns, remembers information, or learns rules to get a reward — for some time now. “Studying tasks that tapped into real cognition opened up whole sets of neural properties you simply don’t see in basic sensory tasks,” says Miller. But the experimental setup rarely changed, and the strengths of classical neuroscience — precision and control — limited the reach of these studies.

Neuroscientists have been studying more cognition-based questions — like how the brain recognizes patterns, remembers information, or learns rules to get a reward — for some time now. “Studying tasks that tapped into real cognition opened up whole sets of neural properties you simply don’t see in basic sensory tasks,” says Miller. But the experimental setup rarely changed, and the strengths of classical neuroscience — precision and control — limited the reach of these studies. The Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge isn’t just long, it’s complicated in a way

The Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge isn’t just long, it’s complicated in a way  Kate Winslet has made a career out of playing strong, confident, forthright women: Lee Miller, Mare Sheehan, Rose DeWitt Bukater, Clementine Kruczynski. Her resume is studded with awards recognition (an Academy Award for Best Actress for 2008’s The Reader, a pair of Emmys for playing the eponymous characters in HBO’s Mare of Easttown in 2021 and Mildred Pierce in 2011, an armful of BAFTAs across a 27-year span) and boasts cumulative box-office earnings in the billions (working with

Kate Winslet has made a career out of playing strong, confident, forthright women: Lee Miller, Mare Sheehan, Rose DeWitt Bukater, Clementine Kruczynski. Her resume is studded with awards recognition (an Academy Award for Best Actress for 2008’s The Reader, a pair of Emmys for playing the eponymous characters in HBO’s Mare of Easttown in 2021 and Mildred Pierce in 2011, an armful of BAFTAs across a 27-year span) and boasts cumulative box-office earnings in the billions (working with  Elon Musk’s personal wealth now

Elon Musk’s personal wealth now  Legend has it that 18th-century Romantic painter Francisco Goya was once a porter here. Ernest Hemingway set the closing scene of The Sun Also Rises at a table in an upstairs dining room, and the signatures of Spanish kings throughout the centuries adorn one of the walls. There is also most definitely a ghost in the wine cellar.

Legend has it that 18th-century Romantic painter Francisco Goya was once a porter here. Ernest Hemingway set the closing scene of The Sun Also Rises at a table in an upstairs dining room, and the signatures of Spanish kings throughout the centuries adorn one of the walls. There is also most definitely a ghost in the wine cellar. I walk around the town in which I live and there aren’t drones in the sky or self-driving cars or sidewalk robots or anything like that. And when I spend time on the internet, aimlessly scrolling social media sites in the dead of night as I attempt to extract a burp from my newborn, I might occasionally see some synthetic images or video, but mostly I see what has always been on these feeds: pictures of people I do and don’t know, memes, and a mixture of news and jokes.

I walk around the town in which I live and there aren’t drones in the sky or self-driving cars or sidewalk robots or anything like that. And when I spend time on the internet, aimlessly scrolling social media sites in the dead of night as I attempt to extract a burp from my newborn, I might occasionally see some synthetic images or video, but mostly I see what has always been on these feeds: pictures of people I do and don’t know, memes, and a mixture of news and jokes. Back in the early 1930s Gilbert Seldes—a literary critic and early champion of popular culture—was asked to contribute an introduction to a volume of stories by Fitz-James O’Brien, now often regarded as the most original American writer of supernatural fiction between Edgar Allan Poe and Ambrose Bierce. At first Seldes declined, confessing that he’d never read anything by the man. But when the publisher jogged his memory, Seldes remembered that in some anthology or another he had in fact come across “The Diamond Lens,” O’Brien’s 1858 account of an obsessive microscopist who discovers an Eden-like world in a drop of water—and falls in love with the beautiful woman who lives in it.

Back in the early 1930s Gilbert Seldes—a literary critic and early champion of popular culture—was asked to contribute an introduction to a volume of stories by Fitz-James O’Brien, now often regarded as the most original American writer of supernatural fiction between Edgar Allan Poe and Ambrose Bierce. At first Seldes declined, confessing that he’d never read anything by the man. But when the publisher jogged his memory, Seldes remembered that in some anthology or another he had in fact come across “The Diamond Lens,” O’Brien’s 1858 account of an obsessive microscopist who discovers an Eden-like world in a drop of water—and falls in love with the beautiful woman who lives in it. Bardot’s significance was never confined to her acting. She mattered because she altered the image of womanhood at a moment when female beauty was expected to reassure. She unsettled instead. Her looseness, physical and emotional, her apparent boredom with approval, her refusal to perform refinement, all suggested a form of autonomy that was felt before it was articulated. She did not argue for freedom. She behaved as if it already belonged to her.

Bardot’s significance was never confined to her acting. She mattered because she altered the image of womanhood at a moment when female beauty was expected to reassure. She unsettled instead. Her looseness, physical and emotional, her apparent boredom with approval, her refusal to perform refinement, all suggested a form of autonomy that was felt before it was articulated. She did not argue for freedom. She behaved as if it already belonged to her. In April 2025, Donald Trump took the stage to mark the 100th day of his second term as US president. You might have expected a moment of triumph. He had reclaimed the presidency, consolidated power within the Republican Party, and issued a vast range of executive orders. But the mood wasn’t celebratory. It was combative. Trump spent most of his time attacking his predecessor Joe Biden, repeating false claims about the 2020 election, denouncing the press, and warning of threats posed by immigrants, ‘radical Left lunatics’ and corrupt elites. The tone was familiar: angry, aggrieved, unrelenting. Even in victory, the focus was on enemies and retribution.

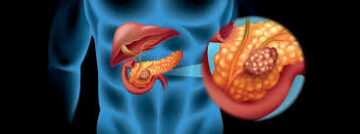

In April 2025, Donald Trump took the stage to mark the 100th day of his second term as US president. You might have expected a moment of triumph. He had reclaimed the presidency, consolidated power within the Republican Party, and issued a vast range of executive orders. But the mood wasn’t celebratory. It was combative. Trump spent most of his time attacking his predecessor Joe Biden, repeating false claims about the 2020 election, denouncing the press, and warning of threats posed by immigrants, ‘radical Left lunatics’ and corrupt elites. The tone was familiar: angry, aggrieved, unrelenting. Even in victory, the focus was on enemies and retribution. A diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is devastating news. Though it makes up only about 3 percent of cancers in the United States, it’s one of the deadliest, and on track for a dark achievement: By 2030, it’s expected to

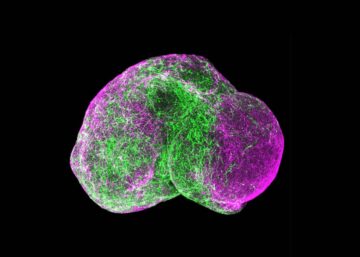

A diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is devastating news. Though it makes up only about 3 percent of cancers in the United States, it’s one of the deadliest, and on track for a dark achievement: By 2030, it’s expected to  When brain organoids were introduced roughly a decade ago, they were a scientific curiosity. The pea-sized blobs of brain tissue grown from stem cells mimicked parts of the human brain, giving researchers a 3D model to study, instead of the usual flat layer of neurons in a dish. Scientists immediately realized they were special. Mini brains developed nearly the whole range of human brain cells, including neurons that sparked with

When brain organoids were introduced roughly a decade ago, they were a scientific curiosity. The pea-sized blobs of brain tissue grown from stem cells mimicked parts of the human brain, giving researchers a 3D model to study, instead of the usual flat layer of neurons in a dish. Scientists immediately realized they were special. Mini brains developed nearly the whole range of human brain cells, including neurons that sparked with