Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Sally Kirkland (1941 – 2025) Actor

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

In Search of Lost Stein

Ryan Ruby in Bookforum:

DESPITE HER REPUTATION as a long-winded writer, Gertrude Stein had a talent for pithiness. Of Oakland, the town where she grew up, she famously remarked: “There is no there, there.” Of one of her literary nemeses, Ezra Pound: “A village explainer, excellent if you were a village, but if not, not.” Of the younger American expat writers who flocked to Paris during the ’20s: “You are all a lost generation.” Of the atomic age: “Everyone gets so much information all day long that they lose their common sense.” Of pithy remarks: “Remarks are not literature.”

DESPITE HER REPUTATION as a long-winded writer, Gertrude Stein had a talent for pithiness. Of Oakland, the town where she grew up, she famously remarked: “There is no there, there.” Of one of her literary nemeses, Ezra Pound: “A village explainer, excellent if you were a village, but if not, not.” Of the younger American expat writers who flocked to Paris during the ’20s: “You are all a lost generation.” Of the atomic age: “Everyone gets so much information all day long that they lose their common sense.” Of pithy remarks: “Remarks are not literature.”

According to Alice B. Toklas, the woman who had for forty years served as her devoted secretary, editor, cook, bouncer, companion, and lover—as well as the narrator of her most famous book—Stein kept her wits and her wit to the very end. On July 27, 1946, the two waited in a hospital in a suburb of Paris, where Stein, who was suffering from stomach cancer, would undergo the surgery that would kill her. Toklas recalls: “I sat next to her and she said to me in the early afternoon, What is the answer? I was silent. In that case, she said, what is the question?”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Padma Lakshmi’s Latest Cookbook is a ‘Love Letter’ to Immigrants

Erin McMullen in Time Magazine:

Padma Lakshmi, a fixture of American culinary television since the early aughts, knows that many people are used to hearing her speak in one language: food. So when she felt called to action in the wake of the 2016 election, frustrated by anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies, she channeled her desire for change into a new TV show—one that highlighted the cuisines of immigrant and Indigenous communities across the U.S.

Padma Lakshmi, a fixture of American culinary television since the early aughts, knows that many people are used to hearing her speak in one language: food. So when she felt called to action in the wake of the 2016 election, frustrated by anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies, she channeled her desire for change into a new TV show—one that highlighted the cuisines of immigrant and Indigenous communities across the U.S.

Taste the Nation, a Hulu docu-series that premiered in 2020, followed Lakshmi—an immigrant herself, having moved to the U.S. from India as a child—as she traversed the country in an effort to learn more about the cultures that have shaped American food for decades. The aptly-named series saw the former host of Top Chef sample Mexican cuisine in Texas, Thai dishes in Nevada, and Greek eats in Florida. It was her “Trojan horse,” a show that used food as a way to make people curious about America, its people, and its history.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, November 14, 2025

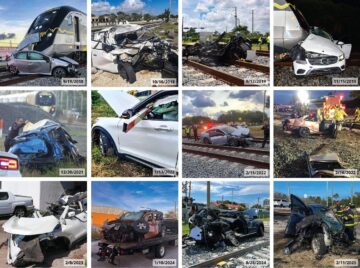

Killer Train

Brittany Wallman, Aaron Leibowitz, Shradha Dinesh, Susan Merriam, Daniel Rivero and Joshua Ceballos at the Miami Herald:

Brightline is the nation’s most dangerous passenger train, reporters found, killing someone every 13 days of service, on average. In addition to those deaths, 99 people have been injured. In at least 101 cases, the train crashed into vehicles, but no one was hurt.

Brightline is the nation’s most dangerous passenger train, reporters found, killing someone every 13 days of service, on average. In addition to those deaths, 99 people have been injured. In at least 101 cases, the train crashed into vehicles, but no one was hurt.

The company has not been found at fault for any of the deaths on its tracks. It has faced at least a dozen lawsuits for deaths and injuries, according to court records. None have gone to trial. Some have been settled for undisclosed amounts. In a written statement, Michael Lefevre, Brightline’s vice president of operations, reiterated what the company has been saying for years — that the deaths were self-inflicted.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

As the dams feeding Tehran run dry, Iran struggles with a dire water crisis

Maziar Motamedi at Al Jazeera:

Authorities are scrambling to provide drinking water across Iran, particularly in the capital, Tehran, as Iranians grapple with the effects of multiple ongoing crises.

Authorities are scrambling to provide drinking water across Iran, particularly in the capital, Tehran, as Iranians grapple with the effects of multiple ongoing crises.

If there is no rain by next month, water will have to be rationed in Tehran; in fact, the city of 10 million may even have to be evacuated, President Masoud Pezeshkian said in a speech on Friday.

While experts say evacuating the city is a last resort that will likely not come to pass, the president’s stark warning is indicative of the mammoth burden facing the country of more than 90 million, its ailing economy reeling under sanctions.

Iran is now grappling with its sixth consecutive year of drought, while heatwaves pushed temperatures above 50 degrees Celsius (122 degrees Fahrenheit) during the summer.

The past water year, ending in late September 2025, was one of the driest on record, with the current year shaping up to be worse, with Iran receiving only 2.3mm (0.09 inches) of precipitation by early November, down by 81 percent compared with the historical average of the same period, the Meteorological Organization said.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Mustafa Suleyman: Could LLMs Be The Route To Superintelligence?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

COP Can’t Cope With Climate Risks

Quico Toro at Persuasion:

The yearly Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change—COP, to habitués—has morphed, over the years, into a kind of travelling circus grotesquely mismatched to the problem it’s meant to address.

The yearly Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change—COP, to habitués—has morphed, over the years, into a kind of travelling circus grotesquely mismatched to the problem it’s meant to address.

There’s a soul-deadening regularity to the proceedings. Tens of thousands of politicians, negotiators, activists, NGO-types, journalists, and hangers-on of every description declare themselves shocked that global carbon emissions are even higher now than they were when they met a year earlier. Looking solemn, they make heartfelt pledges to do better, to really change this time. A year later, they do it all again.

Having gone through this rigamarole thirty times now, you’d think the world would have caught on that the COP process doesn’t work, and doing it harder won’t help.

But why doesn’t it work?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Jena Romantics: F. Schlegel, Novalis & the Athenaeum Journal

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Finding A Baudelaire For Our Time

Barry Schwabsky at The Point:

Everyone agrees that modern poetry in France—and therefore in Europe—starts with Charles Baudelaire. But no one agrees on why. His successors, Arthur Rimbaud and Stéphane Mallarmé, are each in their own way more patently radical, and the same is true of his American contemporary Walt Whitman. How modern do you have to be to be a modern? Compared to their works, those of Baudelaire, despite their sulfurous aroma, are far more traditional; while he was an early adopter of the prose poem, his most influential poetry used received forms. “Baudelaire accomplished what classical prosody had always required, or rather what it had inaugurated. … His prosody has the same spiritual monotony as Racine’s,” Yves Bonnefoy once remarked. And beyond matters of form, some of Baudelaire’s content was familiar too. His exacerbated ambivalence toward his Haitian-born lover Jeanne Duval, the subject of so many of his poems, is as ancient as Catullus’s odi et amo; praise of drunkenness dates back to the Greeks; and his proud sense of damnation, of his “Heart great with rancor and bitter desires,” would have been second-hand news to Lord Byron. Was the “new shudder” that Victor Hugo perceived in Baudelaire’s writing new enough to make him, rather than the last of the Romantics (the one in whose work Romanticism, you might say, curdled), the first of the moderns?

Everyone agrees that modern poetry in France—and therefore in Europe—starts with Charles Baudelaire. But no one agrees on why. His successors, Arthur Rimbaud and Stéphane Mallarmé, are each in their own way more patently radical, and the same is true of his American contemporary Walt Whitman. How modern do you have to be to be a modern? Compared to their works, those of Baudelaire, despite their sulfurous aroma, are far more traditional; while he was an early adopter of the prose poem, his most influential poetry used received forms. “Baudelaire accomplished what classical prosody had always required, or rather what it had inaugurated. … His prosody has the same spiritual monotony as Racine’s,” Yves Bonnefoy once remarked. And beyond matters of form, some of Baudelaire’s content was familiar too. His exacerbated ambivalence toward his Haitian-born lover Jeanne Duval, the subject of so many of his poems, is as ancient as Catullus’s odi et amo; praise of drunkenness dates back to the Greeks; and his proud sense of damnation, of his “Heart great with rancor and bitter desires,” would have been second-hand news to Lord Byron. Was the “new shudder” that Victor Hugo perceived in Baudelaire’s writing new enough to make him, rather than the last of the Romantics (the one in whose work Romanticism, you might say, curdled), the first of the moderns?

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Coming Back To Nicholas of Cusa

Lawrence Weschler at Wondercabinet:

Somehow I keep coming back to Nicholas of Cusa, that late medieval Renaissance man (1401-1464), a devout church leader and mathematical mystic who was at the same time one of the founders of modern experimental science—propagator, for example, of some of the first formal experiments in biology (proving that trees somehow absorb nourishment from the air, and that air, for that matter, has weight) and advocate, among other things, of the notion that the earth, far from being the center of the universe, might itself be in motion around the sun (this a good two generations before Copernicus), and yet, for all that, a cautionary skeptic as to the limits of that kind of quantifiable knowledge and thus, likewise, a critic of the then-reigning Aristotelian/Thomistic worldview. No, he would regularly insist, one could never achieve knowledge of God, or, for that matter, of the wholeness of existence, through the systematic accretion of more and more factual knowledge. Picture, he would suggest, an n-sided equilateral polygon nested inside a circle, and now keep adding to the number of its sides: triangle, square, pentagon, hexagon, and so forth. The more sides you added, the closer it might seem that you were getting to the bounding circle—and yet, he insisted, in another sense, the farther away you would in fact be getting. Because a million-sided regular polygon, say, has, precisely, a million sides and a million angles, whereas a circle has none, or maybe at most one.

Somehow I keep coming back to Nicholas of Cusa, that late medieval Renaissance man (1401-1464), a devout church leader and mathematical mystic who was at the same time one of the founders of modern experimental science—propagator, for example, of some of the first formal experiments in biology (proving that trees somehow absorb nourishment from the air, and that air, for that matter, has weight) and advocate, among other things, of the notion that the earth, far from being the center of the universe, might itself be in motion around the sun (this a good two generations before Copernicus), and yet, for all that, a cautionary skeptic as to the limits of that kind of quantifiable knowledge and thus, likewise, a critic of the then-reigning Aristotelian/Thomistic worldview. No, he would regularly insist, one could never achieve knowledge of God, or, for that matter, of the wholeness of existence, through the systematic accretion of more and more factual knowledge. Picture, he would suggest, an n-sided equilateral polygon nested inside a circle, and now keep adding to the number of its sides: triangle, square, pentagon, hexagon, and so forth. The more sides you added, the closer it might seem that you were getting to the bounding circle—and yet, he insisted, in another sense, the farther away you would in fact be getting. Because a million-sided regular polygon, say, has, precisely, a million sides and a million angles, whereas a circle has none, or maybe at most one.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

Saudade

A thousand years ago a song was sung

near a campfire at night

by a singer who was alone, exiled

perhaps, or seeking;

a song whose words were not meant

to be understood, only to be heard,

offered to the silence

and sung in the key of loss.

It confirmed the universe is empty

and dark and knows nothing of us.

Of what we offer, life takes what it wants

and goes.

Exhausted with living

we all listen for a sound

we don’t expect to hear.

A thousand years ago a singer

tended the last coals of a fire and sang

the most beautiful song ever sung,

which no one heard,

and it is the song I need now.

by Robert Rice

from Rattle #89, Fall 2025

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Want to live a long, healthy life? 6 secrets from Japan’s oldest people

From The World Economic Forum:

On the sub-tropical Japanese islands of Okinawa, they have a saying: Live far enough away from your family so you’re not running into them every day, but close enough to take them a warm bowl of soup – on foot. Many of us during the past 18 months would have benefited from living within walking distance of our family. We’ve had to make do with Zoom calls instead – and the loss of social connection has affected our well-being and mental health.

On the sub-tropical Japanese islands of Okinawa, they have a saying: Live far enough away from your family so you’re not running into them every day, but close enough to take them a warm bowl of soup – on foot. Many of us during the past 18 months would have benefited from living within walking distance of our family. We’ve had to make do with Zoom calls instead – and the loss of social connection has affected our well-being and mental health.

Socializing is one of the reasons many Okinawans live healthily to 100 and older. So says University of Hawaii geriatrician and Director of the Kuakini Center for Translational Research on Aging, Dr. Bradley Willcox, who with his anthropologist twin brother, Craig, of Okinawa International University, has been studying centenarians on the islands for more than 20 years. It’s one of the world’s five Blue Zones, where there are high concentrations of centenarians.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Jane Goodall’s last interview Recorded on 9/23/25

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, November 13, 2025

Philosophy’s long-running civil war heats up a bit

Matt Lutz at Humean Being:

Within the broader discipline of philosophy, there is a split between what is called “analytic philosophy” and what is called “continental philosophy.” The gulf between these two camps is wide, and the dispute between them extremely acrimonious, although it is hard to articulate precisely what the difference between the two is. Any proposed account of this distinction – analytic philosophers are like this, while continentals are like that – will inevitably result in very angry objections. For one thing, any proposed distinction will inevitably mischaracterize several paradigmatic continental or analytic philosophers. But more importantly, the person proposing the distinction is usually a partisan of one camp or the other, and they characterize the distinction in terms that are extremely flattering to their own side. “Analytic philosophers prize rigor and clarity,” says that analytic philosopher, “whereas continentals do not.” “Go fuck yourself,” the continental philosopher replies.

Within the broader discipline of philosophy, there is a split between what is called “analytic philosophy” and what is called “continental philosophy.” The gulf between these two camps is wide, and the dispute between them extremely acrimonious, although it is hard to articulate precisely what the difference between the two is. Any proposed account of this distinction – analytic philosophers are like this, while continentals are like that – will inevitably result in very angry objections. For one thing, any proposed distinction will inevitably mischaracterize several paradigmatic continental or analytic philosophers. But more importantly, the person proposing the distinction is usually a partisan of one camp or the other, and they characterize the distinction in terms that are extremely flattering to their own side. “Analytic philosophers prize rigor and clarity,” says that analytic philosopher, “whereas continentals do not.” “Go fuck yourself,” the continental philosopher replies.

Despite the difficulty with giving a strict characterization, analytic philosophy and continental philosophy have very different vibes.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rats Are Snatching Bats Out of the Air and Eating Them—and Researchers Got It on Video

Sarah Kuta at Smithsonian Magazine:

Rats have gotten a bad reputation over the years for being dirty, garbage-eating carriers of disease. But these ubiquitous rodents are also clever and capable of learning complex tasks, even using their imaginations to navigate in virtual reality.

Rats have gotten a bad reputation over the years for being dirty, garbage-eating carriers of disease. But these ubiquitous rodents are also clever and capable of learning complex tasks, even using their imaginations to navigate in virtual reality.

Now, new research adds another odd skill to their résumés: hunting bats. In a new study published in the journal Global Ecology and Conservation, scientists describe the first-ever observations of brown rats snatching bats out of the air, then chowing down.

The novel behavior is a “remarkable” example of the rodents’ ability to make the most of their environment, the researchers write.

But it may also spell bad news: The two species could be exchanging pathogens—interactions that could eventually trickle down to affect human health—and the rats, which are not native to Germany, might be killing enough bats to harm the local populations.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Joni Mitchell – Live at the Newport Folk Festival 2022

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Grant Sanderson: Why Laplace transforms are so useful

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Notes On Joni Mitchell

Rick Moody at Salamgundi:

1. The day on which we embarked to see Joni Mitchell play the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles (“we” defined as myself, my wife Laurel Nakadate, and our son Theo), having flown west from Boston, was the date of my own parents’ wedding anniversary, namely, October 19.

2. My parents had been divorced since, I think, 1971, or 53 years, on the occasion of the concert. I still think of them on October 19.

3. Is not divorce, any divorce, on the list of “petty wars” that the Joni Mitchell narrator of “Traveller (Hejira)” describes in that bit of song ravishment? (I’m using the demo/early version here.)

4. There are things I find keenly uncomfortable about Los Angeles. I like to walk, but L.A., because of its scale, requires a lot of driving. A constancy of highway transit, yes. A city of travelers.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Modeling the geopolitics of AI development

Alex Amadori, Gabriel Alfour, Andrea Miotti, and Eva Behrens at AI Scenarios:

We model national strategies and geopolitical outcomes under differing assumptions about AI development. We put particular focus on scenarios with rapid progress that enables highly automated AI R&D and provides substantial military capabilities.

Under non-cooperative assumptions—concretely, if international coordination mechanisms capable of preventing the development of dangerous AI capabilities are not established—superpowers are likely to engage in a race for AI systems offering an overwhelming strategic advantage over all other actors.

If such systems prove feasible, this dynamic leads to one of three outcomes:

- One superpower achieves an unchallengeable global dominance;

- Trailing superpowers facing imminent defeat launch a preventive or preemptive attack, sparking conflict among major powers;

- Loss-of-control of powerful AI systems leads to catastrophic outcomes such as human extinction.

Middle powers, lacking both the muscle to compete in an AI race and to deter AI development through unilateral pressure, find their security entirely dependent on factors outside their control: a superpower must prevail in the race without triggering devastating conflict, successfully navigate loss-of-control risks, and subsequently respect the middle power’s sovereignty despite possessing overwhelming power to do otherwise.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.