Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

How to Raise a Genius: Lessons from a 45-Year Study of Supersmart Children

Tom Clynes in Scientific American:

Many of the innovators who are advancing science, technology and culture are those whose unique cognitive abilities were identified and supported in their early years through enrichment programmes such as Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Talented Youth—which Stanley began in the 1980s as an adjunct to SMPY. At the start, both the study and the centre were open to young adolescents who scored in the top 1% on university entrance exams.Pioneering mathematicians Terence Tao and Lenhard Ng were one-percenters, as were Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, Google co-founder Sergey Brin and musician Stefani Germanotta (Lady Gaga), who all passed through the Hopkins centre.

Many of the innovators who are advancing science, technology and culture are those whose unique cognitive abilities were identified and supported in their early years through enrichment programmes such as Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Talented Youth—which Stanley began in the 1980s as an adjunct to SMPY. At the start, both the study and the centre were open to young adolescents who scored in the top 1% on university entrance exams.Pioneering mathematicians Terence Tao and Lenhard Ng were one-percenters, as were Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, Google co-founder Sergey Brin and musician Stefani Germanotta (Lady Gaga), who all passed through the Hopkins centre.

“Whether we like it or not, these people really do control our society,” says Jonathan Wai, a psychologist at the Duke University Talent Identification Program in Durham, North Carolina, which collaborates with the Hopkins centre. Wai combined data from 11 prospective and retrospective longitudinal studies, including SMPY, to demonstrate the correlation between early cognitive ability and adult achievement. “The kids who test in the top 1% tend to become our eminent scientists and academics, our Fortune 500 CEOs and federal judges, senators and billionaires,” he says.

Such results contradict long-established ideas suggesting that expert performance is built mainly through practice—that anyone can get to the top with enough focused effort of the right kind. SMPY, by contrast, suggests that early cognitive ability has more effect on achievement than either deliberate practice or environmental factors such as socio-economic status.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

An Alternative-Medicine Believer’s Journey Back to Science

Alan Levinovitz in Wired:

Jim and Louise Laidler lost their faith on a trip to Disneyland in 2002, while having breakfast in Goofy’s Kitchen.

Jim and Louise Laidler lost their faith on a trip to Disneyland in 2002, while having breakfast in Goofy’s Kitchen.

The Laidlers are doctors, and their sons, Ben and David, had been diagnosed with autism. For several years, on the advice of doctors and parents, the Laidlers treated their children with a wide range of alternative medicine techniques designed to stem or even reverse autistic symptoms. They gave their boys regular supplements of vitamin B12, magnesium, and dimethylglycine. They kept David’s diet free of gluten and casein, heeding the advice of experts who warned that even the smallest bit of gluten would cause severe regression. They administered intravenous infusions of secretin, said to have astonishing therapeutic effects for a high percentage of autistic children.

Using substances known as chelating agents, the Laidlers also worked to rid Ben and David of heavy metals thought to be accumulated through vaccines and environmental pollutants. With a PhD in biology as well as his MD, Jim Laidler had become an expert on chelation, speaking nationally and internationally about it at conferences dedicated to autism and alternative approaches. But by the time the family took a trip to Disneyland, Jim was starting to doubt the attitude fostered at conferences like Defeat Autism Now!, where he first learned about chelation. He cringed when he heard of parents mortgaging their homes to pay for wildly expensive and unproven treatments. Alarms went off when parents and doctors would advocate dangerous protocols—hyper-dosing with vitamin A, using extreme forms of chelation. When he spoke out against them, a prominent conference organizer took him aside and warned him never to criticize anyone’s approach, no matter how crazy or dangerous it seemed.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

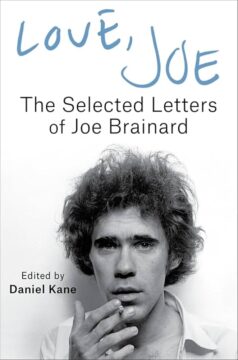

LOVE, JOE: The Selected Letters of Joe Brainard

Dwight Garner at the NYT:

This book review is a Trojan horse. Ostensibly it concerns a collection of letters titled “Love, Joe,” written by the downtown artist and writer Joe Brainard (1941-94) to friends including the poets John Ashbery, Ted Berrigan, Anne Waldman and James Schuyler. Before we get to those letters, a historical wrong must be righted. Next year is the 55th anniversary of the publication of Brainard’s experimental memoir, “I Remember.” I hadn’t read it until I picked it up in preparation to write this piece. Now I consider it one of the best books I know.

This book review is a Trojan horse. Ostensibly it concerns a collection of letters titled “Love, Joe,” written by the downtown artist and writer Joe Brainard (1941-94) to friends including the poets John Ashbery, Ted Berrigan, Anne Waldman and James Schuyler. Before we get to those letters, a historical wrong must be righted. Next year is the 55th anniversary of the publication of Brainard’s experimental memoir, “I Remember.” I hadn’t read it until I picked it up in preparation to write this piece. Now I consider it one of the best books I know.

This newspaper missed two opportunities to review “I Remember.” The first was when the book appeared in 1970. The second was when it anchored a 2012 omnibus called “The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard,” issued by the Library of America. So, let’s spend just a moment on it. It’s a small but real American classic. Each sentence in Brainard’s short, stream-of-consciousness memoir begins with the same words: “I remember.” The book, which chronicles his childhood in Oklahoma in the 1940s and ’50s and his later decades in New York City, dispenses small cubes of pleasure on every page. Its cumulative effect is sly but enormous.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

Stebbin’s Gulch

Ages ago

The water pours

It pours

It pours

Ever along the slant

Of downgrade

Dashing its silver thumbs

Against the rocks

Or pausing to carve

A sudden curled space

Where the flashing fish

Splash or drowse

While the kingfisher overhead

Rattles and stares

And so it continues for miles

This bolt of light,

It’s only industry

As for purpose

There is none,

It is simply

One of those gorgeous things

That was made

To do what it does perfectly

And to last,

As almost nothing does,

Almost forever.

by Mary Oliver

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, December 5, 2024

Playing with Reality: How Games Have Shaped Our World

Julien Crockett in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

JULIEN CROCKETT: You dedicate Playing with Reality to the next generation, writing, “If play is the engine of creation, I cannot wait to see what new worlds you build.” A recurring theme in your book is the primacy of play and games to what it means to be human—that playing games is universal, an instinct. What makes games and play so important to understanding ourselves?

JULIEN CROCKETT: You dedicate Playing with Reality to the next generation, writing, “If play is the engine of creation, I cannot wait to see what new worlds you build.” A recurring theme in your book is the primacy of play and games to what it means to be human—that playing games is universal, an instinct. What makes games and play so important to understanding ourselves?

KELLY CLANCY: Play is something that predates humans. It’s fundamental to how animals engage in and understand the world. It’s how we test and figure out the rules of our environment, how social relationships work. Part of the idea to focus on play in the book was generated from David Graeber and David Wengrow’s book The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (2021), where they go through different ancient societies and show not only how incredibly diverse they were—contrary to the idea that there is a monolithic trajectory from hunter-gatherer to agriculturalist to industrial society—but also how incredibly playful all of these societies were. More recently, at events like Carnival in Renaissance Europe, people would put on costumes and participate in taboo things like gambling, having affairs, and drinking. There were all of these opportunities to release the strictures of society and try something new.

This is something that I think we’re missing in our current society but that maybe the internet is giving us—an opportunity to put on a new mask, a new personality, and to act in a way that we wouldn’t necessarily in our everyday interactions.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

2025 will be the year of AI agents

Azeem Azhar at Exponential View:

I’m at DealBook Summit in NYC today and I just heard Sam Altman speak about his view on the next few years:

I’m at DealBook Summit in NYC today and I just heard Sam Altman speak about his view on the next few years:

I expect that in 2025, we will have systems that people look at, even people who are sceptical of current progress, and say ‘Wow, I did not expect that’. Agents are the thing everyone is talking about for good reason. This idea that you can give an AI system a pretty complicated task, the kind of task you’d give to a very smart human, that takes a while to go off and do and use a bunch of tools and create something of value. That’s the kind of thing I’d expect next year. And that’s a huge deal. If that works as well as we hope it does, that can really transform things.

Agents have been on my roadmap for a while. Last year, I spoke about our billion agent future and invested in a couple of startups building agentic systems. In today’s post, we look at how we think we’ll go from AI assistants like ChatGPT to billions of agents supporting us in the background.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sam Altman on the Future of A.I. and Society

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Cass Sunstein on Campus Free Speech

Yascha Mounk at his own Substack:

Yascha Mounk: You’re an incredibly prolific author who’s influenced me in many ways, but your latest book is on a subject that I’m also very interested in, which is free speech and particularly the role that free speech should play on campus.

This is obviously a timely issue. What do you think that smart people are getting wrong about that subject right now?

Cass Sunstein: Well, I think that one mistake is that people think that universities are covered by the same principles, regardless of whether they’re public or private. And as a legal matter, public universities are governed by the First Amendment and private universities just aren’t. There’s also a lot of talk about incitement without a lot of clarity about what that particularly entails. So if I say something like, “If you don’t buy my book there’s going to be a revolution,” that’s kind of hopelessly useless talk on the part of an author and that would not be regulable as incitement.

Cass Sunstein: Well, I think that one mistake is that people think that universities are covered by the same principles, regardless of whether they’re public or private. And as a legal matter, public universities are governed by the First Amendment and private universities just aren’t. There’s also a lot of talk about incitement without a lot of clarity about what that particularly entails. So if I say something like, “If you don’t buy my book there’s going to be a revolution,” that’s kind of hopelessly useless talk on the part of an author and that would not be regulable as incitement.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Notes From a Pioneer On a Speck in Space

Few things that grow here poison us.

Most of the animals are small.

Those big enough to kill us do it in a way

Easy to understand, easy to defend against.

The air, here, is just what the blood needs.

We don’t us helmets or space suits.

The star, here, doesn’t burn you if you

Stay outside as much as you should.

The worst of our winters are bearable.

Water, both salt and sweet, is everywhere.

The things that live in it are easily gathered.

Mostly, you can eat them raw with safety and pleasure.

Yesterday my wife and I brought back

Shells, driftwood, stones, and other curiosities

Found on the beach of the immense

Fresh-water Sea we live by.

She was al excited by a slender white stone which:

“Exactly fits the hand!”

I couldn’t share her wonder;

Here, almost everything does.

Lew Welsh

from Ring of Bone

Grey Fox Press, 1979

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Science could solve some of the world’s biggest problems. Why aren’t governments using it?

Helen Pearson in Nature:

Nature’s survey — which took place before the US election in November — together with more than 20 interviews, revealed where some of the biggest obstacles to providing science advice lie. Eighty per cent of respondents thought policymakers lack sufficient understanding of science — but 73% said that researchers don’t understand how policy works. “It’s a constant tension between the scientifically illiterate and the politically clueless,” says Paul Dufour, a policy specialist at the University of Ottawa in Canada.

Nature’s survey — which took place before the US election in November — together with more than 20 interviews, revealed where some of the biggest obstacles to providing science advice lie. Eighty per cent of respondents thought policymakers lack sufficient understanding of science — but 73% said that researchers don’t understand how policy works. “It’s a constant tension between the scientifically illiterate and the politically clueless,” says Paul Dufour, a policy specialist at the University of Ottawa in Canada.

But it’s a time of reinvention and evolution in science advice, too. Finland is one country experimenting with different models for providing advice. Many groups, including the US National Academy of Sciences in Washington DC, are trying to speed up the supply of advice to match the rapid pace at which policymakers work, or to incorporate conflicting views. Last year, the United Nations secretary-general, António Guterres, launched a Scientific Advisory Board. Many people in the field say that science-advice systems need further change. Tackling issues such as intergenerational disadvantage, youth mental health, immigration and responses to climate change require different ways of operating, says Peter Gluckman, former chief science adviser to the New Zealand prime minister and now at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. “Science advice is not designed for that at the moment.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Does Teaching Literature and Writing Have a Future?

Phil Christman in Plough:

To wake up one morning and learn that one’s job might soon be “disrupted,” or outright eliminated, by the emergence of an overhyped new technology that excites rich people is – let’s start here – a pretty common experience by now. It puts you in good company. A club that includes linotype-machine operators, taxi drivers, some farm workers, and the original Luddites, but somehow never includes capital owners or their profligate children: this is, all things considered, not a bad club, and one would wish to join it but for the sparsity of the accommodations. But if the prediction of redundancy comes true, this solidarity in misfortune will probably prove cold comfort.

To wake up one morning and learn that one’s job might soon be “disrupted,” or outright eliminated, by the emergence of an overhyped new technology that excites rich people is – let’s start here – a pretty common experience by now. It puts you in good company. A club that includes linotype-machine operators, taxi drivers, some farm workers, and the original Luddites, but somehow never includes capital owners or their profligate children: this is, all things considered, not a bad club, and one would wish to join it but for the sparsity of the accommodations. But if the prediction of redundancy comes true, this solidarity in misfortune will probably prove cold comfort.

Say, for example, you’re a college English teacher, and a significant portion of the nation’s venture capitalists seems convinced that a machine can now do – or will soon do, very soon, just a few more gigatons of water from now – what you are supposedly training your students to do. Say as well that these same machines, supposedly, are only one or two more clicks of Progress’s wheel away from being able to judge and grade the work thus generated. Clearly, you and your thousands of colleagues are now free to seek exciting new opportunities in our ever-moving economy – that is, to reap the punishment that you deserve for having cared about writing and reading in the first place. You ought to have learned to code, a skill that is itself also supposedly on its way to being rendered redundant by this new technology. Funny how that works out.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, December 4, 2024

Starring Ida Lupino

Farran Smith Nehme at The Current:

When Patrick McGilligan interviewed Ida Lupino in 1974, he was already exhibiting a now well-established critical preference: he was far more interested in her directing work. It makes sense, in a way. Director Dorothy Arzner retired in 1943. By the time Lupino directed her first film, in 1949, women feature-film directors in Hollywood consisted of—well, her. She was unique. She was a pioneer.

When Patrick McGilligan interviewed Ida Lupino in 1974, he was already exhibiting a now well-established critical preference: he was far more interested in her directing work. It makes sense, in a way. Director Dorothy Arzner retired in 1943. By the time Lupino directed her first film, in 1949, women feature-film directors in Hollywood consisted of—well, her. She was unique. She was a pioneer.

But, as we hope to illustrate with this twelve-film series on the Criterion Channel, it would be a serious mistake to neglect Ida Lupino’s acting in favor of the eight features she made as a director. (Nor should her considerable work in television be counted out, but that’s another topic.) Lupino was one of the best, most vivid and original actresses in Hollywood, making permanent classics with directors such as Raoul Walsh, Nicholas Ray, Michael Curtiz, and Vincent Sherman. She played “spirited, tough, offbeat” characters, as McGilligan put it. And by her own account, Lupino’s taste in roles shaped what she chose to do as a director. “I liked the strong characters,” she told McGilligan, “something that has some intestinal fortitude, some guts to it. Just a straight role drives me up the wall. Playing a nice woman who just sits there, that’s my greatest limitation.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Ida Lupino – Documentary

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Imperfect Parfit

Daniel Kodsi and John Maier in The Philosophers’ Magazine:

Philosophers tend to tolerate a high degree of personal strangeness in one another. More specifically, they tend not to worry – at least explicitly or on the record – about whether the weird philosophical beliefs and the weird non-philosophical actions of a colleague might have a common source. The methodological norm rather is that ideas must stand or fall on their intrinsic merits; apart from anything else, this is probably good politics. Making the obvious psychological peculiarities of an author too operative a consideration within academic life might risk implicating an impractically large number of people. (And in that case, one probably wouldn’t trust most of them to apply the relevant criteria accurately anyway.) But this does make philosophy different from other areas of life, where we readily make informative connections, in both directions, between the strangeness of the person and the strangeness of his beliefs, often with a view to discrediting one or the other.

Philosophers tend to tolerate a high degree of personal strangeness in one another. More specifically, they tend not to worry – at least explicitly or on the record – about whether the weird philosophical beliefs and the weird non-philosophical actions of a colleague might have a common source. The methodological norm rather is that ideas must stand or fall on their intrinsic merits; apart from anything else, this is probably good politics. Making the obvious psychological peculiarities of an author too operative a consideration within academic life might risk implicating an impractically large number of people. (And in that case, one probably wouldn’t trust most of them to apply the relevant criteria accurately anyway.) But this does make philosophy different from other areas of life, where we readily make informative connections, in both directions, between the strangeness of the person and the strangeness of his beliefs, often with a view to discrediting one or the other.

Even in academic philosophy, however, individual eccentricity sometimes becomes too overwhelming to escape remark. In the case of Derek Parfit, one of the first things either a critic or admirer will acknowledge is just how odd a man he was.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Renaissance In Drawing

Michael Prodger at The New Statesman:

The complicated, multi-figure compositions evolved through studies of groups, individual figures, and through more general drawings of limbs, moving bodies or muscles in action. Among the most beautiful of Leonardo’s preparatory drawings are those showing horses. One red chalk and ink study from the Royal Collection summarises in extraordinary beauty both his powers of observation and his quest for the most telling pictorial moment: the horse is shown rearing but both head and legs are sketched in several positions as he sought the perfect arrangement. They transmit both equine energy and movement, as though he were condensing a flick-book of images into one drawing.

Michelangelo focused on twisting male bodies, treating the musculature with great care but rarely spending time on the faces of his warriors. In one rapid pen and ink sketch he did imagine a melee of mounted combatants similar to Leonardo’s, but perhaps for that very reason he took the idea no further.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Review of “Living on Earth: Life, Consciousness and the Making of the Natural World” by Peter Godfrey-Smith

Alan C. Love in Nature:

Philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith has devoted his career to examining how animal minds evolved. He blends formidable analytical skills with a deep curiosity about the natural world, mostly experienced at first hand in his native Australia. While writing his latest book, Living on Earth, he spent many hours scrutinizing noisy parrots and cockatoos in his back garden, weeks observing gobies building underwater towers made of shells and seaweed and years closely watching how octopuses behave (P. Godfrey-Smith et al. PLoS ONE 17, e0276482; 2022). The result is an inclusive perspective on Earth’s many distinct minds and agents that urges readers to consider humans’ collective choices and their diverse consequences.

Philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith has devoted his career to examining how animal minds evolved. He blends formidable analytical skills with a deep curiosity about the natural world, mostly experienced at first hand in his native Australia. While writing his latest book, Living on Earth, he spent many hours scrutinizing noisy parrots and cockatoos in his back garden, weeks observing gobies building underwater towers made of shells and seaweed and years closely watching how octopuses behave (P. Godfrey-Smith et al. PLoS ONE 17, e0276482; 2022). The result is an inclusive perspective on Earth’s many distinct minds and agents that urges readers to consider humans’ collective choices and their diverse consequences.

Living on Earth offers an extended philosophical meditation on life, mind, the world and our place in it, completing a trilogy of works on the nexus of agency, sensation and felt experience. His 2016 book Other Minds explored octopus cognition and evolution. And Metazoa (2020) appraised the subjective experiences of animals, concluding that there exists an “animal way of being” that arises from the integration of sensory information in nervous systems. This implies that sentience and subjectivity — life-shaping combinations of perception, goals and values — are widespread across the tree of life.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Benedict Evans: AI Eats the World

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

South Koreans Must Not Let Their President’s Failed Self-Coup Go to Waste

Quico Toro at Persuasion:

The political spasm that gripped South Korea last night has been widely seen as a portent of doom, but it need not be. Taking a page from Peru’s political playbook, Yoon Suk Yeol, South Korea’s unpopular, thin-skinned, ineffective president attempted an autogolpe, or self-coup—a power-play against the institutions of the country he was elected to lead.

The political spasm that gripped South Korea last night has been widely seen as a portent of doom, but it need not be. Taking a page from Peru’s political playbook, Yoon Suk Yeol, South Korea’s unpopular, thin-skinned, ineffective president attempted an autogolpe, or self-coup—a power-play against the institutions of the country he was elected to lead.

Following a series of deadlocked budget negotiations with the opposition-run legislature, Yoon stunned the nation with a late-night speech declaring martial law on the flimsy pretext that the state was under threat. The move would formally put the country under military rule, suspending guarantees of free speech and assembly. Yoon sent soldiers into parliament to try to intimidate opposition lawmakers.

The power grab fell apart after a night full of drama when parliament voted to reverse the martial law decree, forcing Yoon to backtrack a scant six hours after his initial move. The near-instant collapse of this power-grab made for dramatic news footage that seemed to show a democracy spiraling into crisis. And yet, if deftly handled, the whole episode could well leave South Korea’s democracy stronger.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

The Association of Man and Woman

Whatever badness there was

sometimes

was not of us,

but between us.

Because there was goodness,

which felt like a sure base.

While badness felt only

like incidents upon it.

The badness was only

the way you and I needed to behave,

sometimes.

Not what we were.

The badness was only

a small,

transient,

insignificant

pain,

Like the tiny, instant

pain

from the prick of a rose’s thorn,

taking joy,

for a second,

away from the fragrance of the rose.

by Peggy Freydberg

from Poems From the Pond

—The title is from a poem called “East Coker” by T.S. Eliot in Four Quartets.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.