See also this by Scott Aaronson.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Theo Padnos at Persuasion:

In the fall of 2012, when Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the military power now in charge of Syria, was a mere minor terrorist organization, a band of their fighters in Aleppo took me prisoner. Back then they were known as Jabhat al-Nusra. I remained in the group’s custody for two years—often in solitary confinement cells, but not always. During this time, it often happened that news of some stupendous victory would make its way, via the fighters’ two-way radios, into our prisons. It was a surreal experience then to listen as a government checkpoint got blown into the sky, for instance, or a truckload of government troops fell into my captors’ hands.

In the fall of 2012, when Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the military power now in charge of Syria, was a mere minor terrorist organization, a band of their fighters in Aleppo took me prisoner. Back then they were known as Jabhat al-Nusra. I remained in the group’s custody for two years—often in solitary confinement cells, but not always. During this time, it often happened that news of some stupendous victory would make its way, via the fighters’ two-way radios, into our prisons. It was a surreal experience then to listen as a government checkpoint got blown into the sky, for instance, or a truckload of government troops fell into my captors’ hands.

What’s going on now, however, is surreal beyond anything I saw or heard when I was in Syria. I’ve spent the past few days watching my former captors’ wildest dreams come true. Actually, I suspect that all Syrians, in every corner of the world, are watching these events unfold in a mood of unremitting shock and awe.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Patricia Craig at the Dublin Review of Books:

The thing that had precipitated Warner into the literary limelight, and earned her quite a lot of money, was her novel of 1926, Lolly Willowes. As an assertion of female autonomy and idiosyncrasy, it was both timely and captivating. It was also prescient, with its theme of decamping to the country about to be enacted in the life of its author (though perhaps without so sorcerous a resolution). Laura (Lolly) Willowes is a wry old-maidish lady occupying a rather put-upon role in the London household of her married brother, when she suddenly takes flight to a hamlet in the Chilterns called Great Mop, enters into a compact with the Devil and becomes a witch. Despite its subject matter, the book is not excessively whimsical – or its whimsey is tempered by a stern ironic overtone. A style at once mischievous and elegant is one of Warner’s hallmarks, whether it’s applied to a mediaeval nunnery beset by money worries (The Corner That Held Them, 1948), the beguiling and ruthless Cat’s Cradle Book (1960), or the distinctly unfairylike Kingdoms of Elfin (1977), her last subversive flight-of-fancy, carried out with an eldritch inventiveness.

The thing that had precipitated Warner into the literary limelight, and earned her quite a lot of money, was her novel of 1926, Lolly Willowes. As an assertion of female autonomy and idiosyncrasy, it was both timely and captivating. It was also prescient, with its theme of decamping to the country about to be enacted in the life of its author (though perhaps without so sorcerous a resolution). Laura (Lolly) Willowes is a wry old-maidish lady occupying a rather put-upon role in the London household of her married brother, when she suddenly takes flight to a hamlet in the Chilterns called Great Mop, enters into a compact with the Devil and becomes a witch. Despite its subject matter, the book is not excessively whimsical – or its whimsey is tempered by a stern ironic overtone. A style at once mischievous and elegant is one of Warner’s hallmarks, whether it’s applied to a mediaeval nunnery beset by money worries (The Corner That Held Them, 1948), the beguiling and ruthless Cat’s Cradle Book (1960), or the distinctly unfairylike Kingdoms of Elfin (1977), her last subversive flight-of-fancy, carried out with an eldritch inventiveness.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

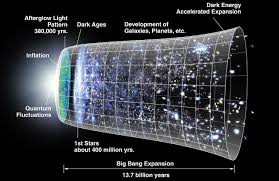

Daniel Linford at Aeon Magazine:

As the 20th century progressed, questions began to emerge about the Big Bang. Was it truly the Universe’s origin? The observable Universe may once have expanded from a hot, dense state, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the entire Universe did so, or that there was nothing before the hot, dense state.

As the 20th century progressed, questions began to emerge about the Big Bang. Was it truly the Universe’s origin? The observable Universe may once have expanded from a hot, dense state, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the entire Universe did so, or that there was nothing before the hot, dense state.

The FLRW models also came under criticism. Each of them assumed that the Universe is spatially homogeneous and isotropic. Scientists wanted to know if the catastrophe showing up in some FLRW models was a byproduct of such unrealistic assumptions. Because the Einstein field equations are so difficult to solve in anything but the simplest cases, scientists turned to Newton’s theory of gravity for guidance. In some Newtonian models – which involve FLRW-like equations – there’s also a past cataclysm where the gravitational field becomes undefined. But unlike in the FLRW models, Newtonian theory can be extended past the cataclysm.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Kyle Buchanan in The New York Times:

Nicole Kidman’s eyes widened. “Haven’t you been to the Rockettes?” she asked. “I go every year. Oh yeah, I’m obsessed!”

Nicole Kidman’s eyes widened. “Haven’t you been to the Rockettes?” she asked. “I go every year. Oh yeah, I’m obsessed!”

Over celery root soup at the Empire Diner in Manhattan last week, the 57-year-old Oscar winner regaled me with stories about the high-kicking Christmas spectacular, which she had attended the night before with her children and husband, the singer Keith Urban: “I was saying to my husband, ‘Why do we love it so much?’ And he said, ‘Because it’s a memory. You’re remembering the kid in you.’” Lately, Kidman has been thinking a lot about this sort of thing, tracing her life and career as part of a continuum. Her new film, “Babygirl,” is one such reconnection: Though she has recently been seen in splashy streaming series like “The Perfect Couple” and “Lioness: Special Ops,” it marks a return to the kind of risky, auteur-driven filmmaking she used to be acclaimed for.

“Babygirl” could earn Kidman her sixth Oscar nomination and has already won her the prestigious Volpi Cup for best actress at the Venice Film Festival in September, though Kidman had to miss that ceremony after the death of her mother, Janelle, at 84.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Morgan Meis at The Easel:

“So strong is the belief in life what is most fragile in life–real life, I mean–that in the end this belief is lost.” This is the first sentence of André Breton’s famous, infamous, notorious, and rarely actually read first Surrealist Manifesto. Breton was born in a small town in Normandy, France in 1896. He was thus a very young man at the outbreak of WWI. As for nearly everyone of that generation, the war was a defining and devastating experience. I myself had an obsession with learning about WWI around ten years ago. I remember reading some first-person accounts of soldiers describing the experience of gas attacks in the trenches of the Western Front. I had to put the book down. It was one of the few times in my life that I found myself literally unable to read through my tears.

“So strong is the belief in life what is most fragile in life–real life, I mean–that in the end this belief is lost.” This is the first sentence of André Breton’s famous, infamous, notorious, and rarely actually read first Surrealist Manifesto. Breton was born in a small town in Normandy, France in 1896. He was thus a very young man at the outbreak of WWI. As for nearly everyone of that generation, the war was a defining and devastating experience. I myself had an obsession with learning about WWI around ten years ago. I remember reading some first-person accounts of soldiers describing the experience of gas attacks in the trenches of the Western Front. I had to put the book down. It was one of the few times in my life that I found myself literally unable to read through my tears.

Breton spent much of his wartime years at a neurological ward in the city of Nantes as a stretcher bearer and nurse. After Nantes, Breton was a student at the psychiatric clinic for the Second Army in Saint-Dizier. There he was to come into contact with many soldiers suffering from shell shock. Breton became, understandably, preoccupied with madness, neurological disorders, and then, through a correspondence with Sigmund Freud, the emerging psychoanalytic theories of the unconscious. Madness seemed to Breton to make much more sense of the world, inner and outer, than any other theory, especially theories that stressed the rational nature of human, beast, and cosmos.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

David A. Kessler in the New York Times:

As Donald Trump gets ready to return to the White House on Jan. 20, he must be prepared to tackle one issue immediately: the possibility that the spreading avian flu might mutate to enable human-to-human transmission.

As Donald Trump gets ready to return to the White House on Jan. 20, he must be prepared to tackle one issue immediately: the possibility that the spreading avian flu might mutate to enable human-to-human transmission.

I was the Biden administration’s chief science officer during Covid-19. I was a co-leader of Operation Warp Speed, which began in Mr. Trump’s first term to accelerate the development of Covid-19 vaccines. I worked on the purchase and rollout of hundreds of millions of doses and on developing antiviral treatments. One of my jobs was to assess the trajectory of the virus.

Now I am back at my job teaching at the medical school at the University of California, San Francisco. I have been monitoring the spread of bird flu, also known as H5N1, and discussing the situation with colleagues around the country. My concern is growing.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

Excessive prices charged by health care providers are overwhelmingly the reason why Americans’ health care costs so cripplingly much. But they’ve outsourced the actual collection of those fees to insurance companies, so that your experience in the medical system feels smooth and friendly and comfortable. The insurance companies are simply hired to play the bad guy — and they’re paid a relatively modest fee for that service. So you get to hate UnitedHealthcare and Cigna, while the real people taking away your life’s savings and putting you at risk of bankruptcy get to play Mother Theresa.

Excessive prices charged by health care providers are overwhelmingly the reason why Americans’ health care costs so cripplingly much. But they’ve outsourced the actual collection of those fees to insurance companies, so that your experience in the medical system feels smooth and friendly and comfortable. The insurance companies are simply hired to play the bad guy — and they’re paid a relatively modest fee for that service. So you get to hate UnitedHealthcare and Cigna, while the real people taking away your life’s savings and putting you at risk of bankruptcy get to play Mother Theresa.

So the way to make our health care system affordable is not to browbeat insurers, in the hope that they will be able to reduce their profits and pay for us to have cheap health care. Insurance companies simply do not have the power to do that, even if you threaten to shoot them. What we need is to reduce costs within the actual medical system itself.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

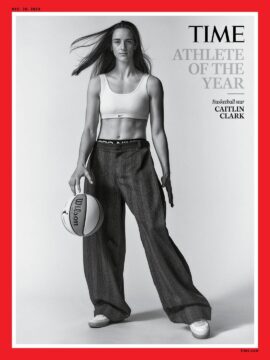

Sean Gregory in Time Magazine:

Few jobs require less physical exertion than rebounding for Caitlin Clark. On an early-November morning in downtown Indianapolis, Clark, the two-time college national player of the year for the University of Iowa, reigning WNBA Rookie of the Year from the Indiana Fever, and emergent American sports icon, sprints to different spots along the three-point line at the Fever practice gym, trying to bang as many shots as possible over a six-minute span. A Fever coach has tasked me with standing under the basket to retrieve her misses. But as Clark runs all over the court to launch long-range bombs, I barely have to move. Swish, swish, swish. She hits 14 shots in a row. A dozen in a row. Eleven in a row. Swish, swish, swish. Nine in a row. Another nine.

Few jobs require less physical exertion than rebounding for Caitlin Clark. On an early-November morning in downtown Indianapolis, Clark, the two-time college national player of the year for the University of Iowa, reigning WNBA Rookie of the Year from the Indiana Fever, and emergent American sports icon, sprints to different spots along the three-point line at the Fever practice gym, trying to bang as many shots as possible over a six-minute span. A Fever coach has tasked me with standing under the basket to retrieve her misses. But as Clark runs all over the court to launch long-range bombs, I barely have to move. Swish, swish, swish. She hits 14 shots in a row. A dozen in a row. Eleven in a row. Swish, swish, swish. Nine in a row. Another nine.

Sure, she’s putting on this display in practice. But her ability is still mesmerizing. Clark, 22, takes shots with a degree of difficulty never before witnessed in the women’s game; her signature 30-ft. launches, from near half-court on team logos across America, are akin to home-run balls, hanging high in the air. Can she actually make that flabbergasting attempt? Yes! it turns out. Over and over again.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Davide Castelvecchi in Nature:

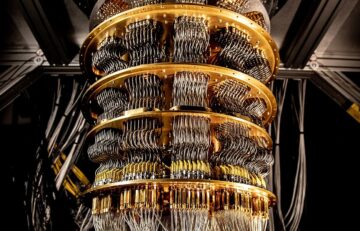

Researchers at Google have built a chip that has enabled them to demonstrate the first ‘below threshold’ quantum calculations — a key milestone in the quest to build quantum computers that are accurate enough to be useful. The experiment, described on 9 December in Nature1, shows that with the right error-correction techniques, quantum computers can perform calculations with increasing accuracy as they are scaled up — with the rate of this improvement exceeding a crucial threshold. Current quantum computers are too small and too error-prone for most commercial or scientific applications.

Researchers at Google have built a chip that has enabled them to demonstrate the first ‘below threshold’ quantum calculations — a key milestone in the quest to build quantum computers that are accurate enough to be useful. The experiment, described on 9 December in Nature1, shows that with the right error-correction techniques, quantum computers can perform calculations with increasing accuracy as they are scaled up — with the rate of this improvement exceeding a crucial threshold. Current quantum computers are too small and too error-prone for most commercial or scientific applications.

“This has been a goal for 30 years,” said Michael Newman, a research scientist at Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, California, at a press conference announcing the feat. The achievement means that by the end of the decade, quantum computers could enable scientific discoveries that are impossible even with the most powerful supercomputers imaginable, said Charina Chou, the chief operating officer of Google’s quantum-computing arm. “That’s the reason we’re building these things in the first place,” Newman added.

“This work shows a truly remarkable technological breakthrough,” says Chao-Yang Lu, a quantum physicist at the University of Science and Technology of China in Shanghai.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Nathaniel Scharping at Noema:

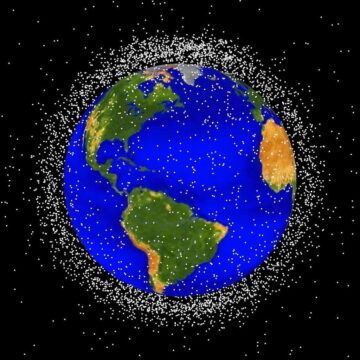

“Everywhere that humans go, they cause ecological problems. The environmental history is clear about this,” Daniel Capper, an adjunct professor of philosophy at the Metropolitan State University of Denver, who is a vocal proponent of such a movement, recently told me. Capper, who has a Walt Whitman beard and speaks with a genial kind of urgency, argues that commonly-held beliefs about the value of land and wilderness on Earth should hold just as much sway in space. He is part of a small but growing chorus of intellectuals who argue that we must carve out protections sooner rather than later — backed by a concrete theoretical and legal framework — for certain areas of the solar system. The United Nations has convened a working group on the use of space resources, and the International Astronomical Union has set up a different working group to delineate places of special scientific value on the moon.

“Everywhere that humans go, they cause ecological problems. The environmental history is clear about this,” Daniel Capper, an adjunct professor of philosophy at the Metropolitan State University of Denver, who is a vocal proponent of such a movement, recently told me. Capper, who has a Walt Whitman beard and speaks with a genial kind of urgency, argues that commonly-held beliefs about the value of land and wilderness on Earth should hold just as much sway in space. He is part of a small but growing chorus of intellectuals who argue that we must carve out protections sooner rather than later — backed by a concrete theoretical and legal framework — for certain areas of the solar system. The United Nations has convened a working group on the use of space resources, and the International Astronomical Union has set up a different working group to delineate places of special scientific value on the moon.

Some researchers have proposed creating a planetary park system in space, while others advocate for a circular space economy that minimizes the need for additional resources.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Annie Ernaux at the Paris Review:

If it hadn’t been for a philosophy classmate at the Lycée Jeanne-d’Arc, I never would have entered the municipal library. I wouldn’t have dared. I vaguely assumed it was open only to university students and professors. Not at all, my classmate told me, everyone’s allowed in, you can even settle down and work there. It was winter. When I would return after class to my closet-size room in the Catholic girls’ dorm, I found it gloomy and awfully chilly. Going to a café was out of the question, I didn’t have any money. The thought of working on my philosophy essays, surrounded by books, somewhere that was surely well heated, was an appealing prospect. The first time I entered the municipal library, at once shy and determined, I suppose, I was struck by the silence, by the sight of people reading or writing as they sat at long rows of tables pushed together and overhung by lamps. I was struck by its hushed and studious atmosphere, which had something religious about it. There was that very particular smell—a little like incense—which I would rediscover later, elsewhere, in other venerable libraries. A sanctuary that required treading cautiously, almost on tiptoe: the opposite of the commotion and confusion of the lycée. An impressive and severe world of knowledge. I didn’t know its rituals, which I had to learn: how to consult the card catalogue, separated into “Authors” and “Subjects”; how to record the call numbers accurately; how to deposit the card into a basket, before waiting, occasionally a long time, sometimes shorter, for the requested book. I got into the habit of coming to the library regularly and writing my philosophy essays there.

If it hadn’t been for a philosophy classmate at the Lycée Jeanne-d’Arc, I never would have entered the municipal library. I wouldn’t have dared. I vaguely assumed it was open only to university students and professors. Not at all, my classmate told me, everyone’s allowed in, you can even settle down and work there. It was winter. When I would return after class to my closet-size room in the Catholic girls’ dorm, I found it gloomy and awfully chilly. Going to a café was out of the question, I didn’t have any money. The thought of working on my philosophy essays, surrounded by books, somewhere that was surely well heated, was an appealing prospect. The first time I entered the municipal library, at once shy and determined, I suppose, I was struck by the silence, by the sight of people reading or writing as they sat at long rows of tables pushed together and overhung by lamps. I was struck by its hushed and studious atmosphere, which had something religious about it. There was that very particular smell—a little like incense—which I would rediscover later, elsewhere, in other venerable libraries. A sanctuary that required treading cautiously, almost on tiptoe: the opposite of the commotion and confusion of the lycée. An impressive and severe world of knowledge. I didn’t know its rituals, which I had to learn: how to consult the card catalogue, separated into “Authors” and “Subjects”; how to record the call numbers accurately; how to deposit the card into a basket, before waiting, occasionally a long time, sometimes shorter, for the requested book. I got into the habit of coming to the library regularly and writing my philosophy essays there.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

They like to write

where people are.

They like a little noise

with their silence.

They want to look up

and see something.

They want to be surprised.

They like the flow

of bodies around them.

Or perhaps it’s just loneliness–

yes, that too.

But more than that:

they like the atmosphere

a little smoke laden.

They like aromas–

coffee, tobacco, meat frying.

They like the sudden revelation

as eyes look off

or blur with tears

looking across a table.

Where others court eternity,

they’re in love with the moment

in all its tawdriness and glory,

that instant when truth appears

out of nowhere–a truth

as simple and as natural

as people sitting together

in a room over coffee

in all their vulnerability

and their humanness.

by Albert Huffstickler

from Poetic Outlaws

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Justin Taylor at Bookforum:

The Bob Dylan Archive had long been a subject of rumor and legend. Few outside the singer’s inner circle knew for sure whether it existed, let alone what it contained. It was kind of hard to picture Mr. Dont Look Back himself boxing up old notebooks for posterity. But if he didn’t, someone did. When the sale was announced in March 2016, the New York Times described it as “deeper and more vast than even most Dylan experts could imagine, promising untold insight into the songwriter’s work. . . . A private trove of his work, dating back to his earliest days as an artist, including lyrics, correspondence, recordings, films and photographs.”

The Bob Dylan Archive had long been a subject of rumor and legend. Few outside the singer’s inner circle knew for sure whether it existed, let alone what it contained. It was kind of hard to picture Mr. Dont Look Back himself boxing up old notebooks for posterity. But if he didn’t, someone did. When the sale was announced in March 2016, the New York Times described it as “deeper and more vast than even most Dylan experts could imagine, promising untold insight into the songwriter’s work. . . . A private trove of his work, dating back to his earliest days as an artist, including lyrics, correspondence, recordings, films and photographs.”

Steadman Upham, then the president of the University of Tulsa, promised that “we will be set up for serious scholars and for people who have a record of being Dylanologists.” Upham died in 2017, and GKFF has since bought out the university’s stake in the Archive, but the promise of access has been kept. Two early hires were the curator Michael Chaiken (who has worked on the archives of Norman Mailer, Nicholas Ray, and D. A. Pennebaker), and the poet/biographer/Dylan-freak Robert Polito. Though it would be years before the Center would open its doors, Chaiken and Polito began bringing writers to Tulsa.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Kristie Frederick Daugherty at Literary Hub:

When Taylor Swift announced the title of her new album The Tortured Poets Department at the Grammy Awards in February, a question popped into my mind: How can poets and poetry enter into conversation with Swift? As a debut-era Swiftie, I knew that her lyrics contain all of the elements of poetry, and that her songwriting is simply unparalleled and literary.

When Taylor Swift announced the title of her new album The Tortured Poets Department at the Grammy Awards in February, a question popped into my mind: How can poets and poetry enter into conversation with Swift? As a debut-era Swiftie, I knew that her lyrics contain all of the elements of poetry, and that her songwriting is simply unparalleled and literary.

As quickly as the question formed in my mind, so did an answer: Ask the best poets writing today to respond with a poem to one specific song of Swift’s without using direct lyrics or titles; then, create a one-of-a-kind ekphrastic poetry anthology which leans into the spirit of Swift’s songwriting, highlighting the way she interacts with her huge fan base whom she has trained to search for “Easter Eggs” in everything from her songwriting to the clothes she wears.

I started with Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Diane Seuss, who not only said yes, but also offered a list of a poets to contact. From that moment the project blossomed into something absolutely beautiful, with 113 poets joyfully agreeing to take part.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.