Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

On Evgeny Sholpo’s Variophone

Lauren Rosati at Artforum:

IN THE SUMMER OF 1917, the Russian engineer and inventor Evgeny Sholpo (1891–1951) wrote “The Enemy of Music,” a polemical science-fiction essay describing a colossal instrument he called the Mechanical Orchestra. Combining miles of slatted black paper tape with a network of electrical wires, pipes, levers, tuning forks, sine wave oscillators, and horns, this fictional sound machine allowed a piece of music to unfold automatically, rendering the musical performer obsolete. “Now,” Sholpo proclaimed, “we will receive ready-made pieces of music according to a specific recipe.” Years later, while working at the Central Laboratory of Wire Communication, a Soviet film lab in Leningrad, Sholpo attempted to bring this speculative project to life, incorporating elements of the fictive Mechanical Orchestra into a functional device called the Variophone, a proto-synthesizer used for scoring films that could reproduce—theoretically—any spoken or musical sound using abstract visual forms cut from paper. The Bureau of Realization of Inventions at the state-run film production company Lenfilm Studios agreed to fund the project; Sholpo built the first prototype in late 1931.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Falling for Fungi

Bob Hirshon in Discover Magazine:

For thousands of years, people have been using fungi to bake bread and brew beer (yeasts), as nutritious foods (mushrooms and truffles), and, more recently, as a source of life-saving antibiotics (penicillin, neomycin and many more). And yet, an estimated 95% of all fungus species remain undiscovered. Fortunately, thousands of energetic citizen scientists like you can help explore this diverse and fascinating kingdom of organisms, thanks to projects like FUNDIS, Mushroom Observer and others featured in this newsletter. And in many parts of the world, October is prime mushroom season.

For thousands of years, people have been using fungi to bake bread and brew beer (yeasts), as nutritious foods (mushrooms and truffles), and, more recently, as a source of life-saving antibiotics (penicillin, neomycin and many more). And yet, an estimated 95% of all fungus species remain undiscovered. Fortunately, thousands of energetic citizen scientists like you can help explore this diverse and fascinating kingdom of organisms, thanks to projects like FUNDIS, Mushroom Observer and others featured in this newsletter. And in many parts of the world, October is prime mushroom season.

Also, October is the perfect time to contribute migratory bird sightings to help monitor and protect birds! Learn more at SciStarter.org/flyways and through our latest SciStarter podcast episode. Whether you’re looking down at shrooms or up at birds, this is the perfect month to enjoy nature and contribute to citizen science!

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The End of the Ivy League?

Max Krupnick in Harvard Magazine:

With one minute left in Harvard’s last men’s basketball game of the 2023-2024 season, sophomore Chisom Okpara drove toward the basket, leaped, and released the ball. It clanked off the rim back into his hands. On the second attempt, he made the shot, his twenty-fifth point of the game. He did not know that would be his final Crimson bucket.

With one minute left in Harvard’s last men’s basketball game of the 2023-2024 season, sophomore Chisom Okpara drove toward the basket, leaped, and released the ball. It clanked off the rim back into his hands. On the second attempt, he made the shot, his twenty-fifth point of the game. He did not know that would be his final Crimson bucket.

Okpara was happy with his team, academics, and social life. But in April, star first-year point guard Malik Mack entered the transfer portal, which allowed coaches from other schools to recruit him. Soon after, fellow Ivy League sophomores Danny Wolf (Yale) and Kalu Anya (Brown) followed suit. Anya, a childhood friend, counseled Okpara to “just enter your name,” Okpara recalls. “You don’t know what’s going to happen. You can always come back.” Once Okpara entered the transfer portal, schools ranging from Auburn and Texas to Stanford and Vanderbilt pursued him. These schools, he said, told him he could make between $200,000 and $500,000 by playing for their basketball team. On May 22, he committed to Stanford, where he will play against stronger competitors while earning a significant amount of money.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Heraclitus: Pre-Socratic Philosophy

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

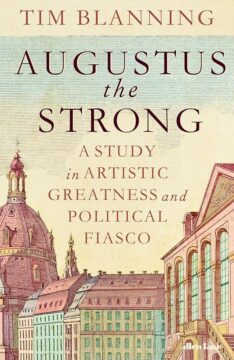

Augustus the Strong: A Study in Artistic Greatness and Political Fiasco

Ritchie Robertson at Literary Review:

Unsuccessful in politics and war, Augustus turned to culture. He transformed Dresden into a city which, even after the notorious bombing raid of February 1945, is still handsome. The highlights include the Zwinger, a palace complex that served as a setting for festivities, the Frauenkirche and the 437-metre-long Augustus Bridge, which linked the centre with the New Town on the other side of the Elbe, helping to create an integrated urban landscape. Next door to the Zwinger, Augustus built the largest opera house in Germany. Blanning enthuses about his success in attracting architects, artists and musicians to Saxony, the most famous being Johann Sebastian Bach, who arrived in Leipzig, Saxony’s other main city, in 1723.

Unsuccessful in politics and war, Augustus turned to culture. He transformed Dresden into a city which, even after the notorious bombing raid of February 1945, is still handsome. The highlights include the Zwinger, a palace complex that served as a setting for festivities, the Frauenkirche and the 437-metre-long Augustus Bridge, which linked the centre with the New Town on the other side of the Elbe, helping to create an integrated urban landscape. Next door to the Zwinger, Augustus built the largest opera house in Germany. Blanning enthuses about his success in attracting architects, artists and musicians to Saxony, the most famous being Johann Sebastian Bach, who arrived in Leipzig, Saxony’s other main city, in 1723.

Augustus was determined to outshine other Baroque rulers in the scale and splendour of the festivities he staged. In 1719, his only legitimate son, Frederick Augustus, married Archduchess Maria Josepha of Austria, daughter of the recently deceased Emperor Joseph I.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

Beer Bottle

In the burned-

out highway

ditch the throw-

away beer

bottle lands

standing up

unbroken,

like a cat

thrown off

of a roof

to kill it,

landing hard

and dazzled

in the sun,

right side up;

sort of a

miracle

by Ted Kooser

from Strong Measures

Harper Collins, 1986

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, October 21, 2024

Have you ever wanted to step into a painting?

Brooks Riley in Art at First Sight:

A painting is not something we step into. We might crave a landscape, a room, a street, a scene or a background, but we can’t inhabit the painter’s vision of it. Our eyes inch closer as they focus on areas of the work, but the view stops there: We remain outsiders, left out in the cold.

A painting is not something we step into. We might crave a landscape, a room, a street, a scene or a background, but we can’t inhabit the painter’s vision of it. Our eyes inch closer as they focus on areas of the work, but the view stops there: We remain outsiders, left out in the cold.

Nowhere have I felt this as much as in the 10th century Southern Tang era painted scroll The Night Revels of Han Xizai, a work I fell in love with for a special reason: I wanted to be there. I wanted to step inside that painted scroll and move among the participants in the low intimate light of a nighttime gathering—joining what looked to be a mondain salon where socializing was stirred with art and music as the guests sipped tea and other beverages, sat around an ancient booth designed for lively conversation, plopped casually on a king-sized daybed, arm propped on bended knee (a sitting pose I recognize from an old friend), or joined in the music-making with percussion or flute.

There is so much going on in this scroll—a 12th-century copy of the original by Gu Hongzhong—only some of it mysterious.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Dario Amodei: How AI Could Transform the World for the Better

Dario Amodei at his own website:

I think and talk a lot about the risks of powerful AI. The company I’m the CEO of, Anthropic, does a lot of research on how to reduce these risks. Because of this, people sometimes draw the conclusion that I’m a pessimist or “doomer” who thinks AI will be mostly bad or dangerous. I don’t think that at all. In fact, one of my main reasons for focusing on risks is that they’re the only thing standing between us and what I see as a fundamentally positive future. I think that most people are underestimating just how radical the upside of AI could be, just as I think most people are underestimating how bad the risks could be.

I think and talk a lot about the risks of powerful AI. The company I’m the CEO of, Anthropic, does a lot of research on how to reduce these risks. Because of this, people sometimes draw the conclusion that I’m a pessimist or “doomer” who thinks AI will be mostly bad or dangerous. I don’t think that at all. In fact, one of my main reasons for focusing on risks is that they’re the only thing standing between us and what I see as a fundamentally positive future. I think that most people are underestimating just how radical the upside of AI could be, just as I think most people are underestimating how bad the risks could be.

In this essay I try to sketch out what that upside might look like—what a world with powerful AI might look like if everything goes right. Of course no one can know the future with any certainty or precision, and the effects of powerful AI are likely to be even more unpredictable than past technological changes, so all of this is unavoidably going to consist of guesses. But I am aiming for at least educated and useful guesses, which capture the flavor of what will happen even if most details end up being wrong. I’m including lots of details mainly because I think a concrete vision does more to advance discussion than a highly hedged and abstract one.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Liberals have forgotten that in order for our lives not to be nasty, brutish and short, we need stability

Jennifer M Morton in Aeon:

Alongside equality, freedom and opportunity, fear has long played a powerful role in political discourse. In ordinary life, fear is often a fitting response to danger. If you encounter a snake while out on a hike, fear will lead you to back away and exercise caution. If the snake is poisonous, fear will have saved your life. By contrast, the fears that dominate political discourse are less concrete. We are told to fear elites, terrorists, religious zealots, godless atheists, sexists, feminists, Marxists and the enemies of democracy. Yet even as these purported poisons are less obviously lethal, political rhetoricians have long understood that making them salient is a powerful way to shape citizens’ motivations. As Donald Trump told Bob Woodward: real power is fear.

Alongside equality, freedom and opportunity, fear has long played a powerful role in political discourse. In ordinary life, fear is often a fitting response to danger. If you encounter a snake while out on a hike, fear will lead you to back away and exercise caution. If the snake is poisonous, fear will have saved your life. By contrast, the fears that dominate political discourse are less concrete. We are told to fear elites, terrorists, religious zealots, godless atheists, sexists, feminists, Marxists and the enemies of democracy. Yet even as these purported poisons are less obviously lethal, political rhetoricians have long understood that making them salient is a powerful way to shape citizens’ motivations. As Donald Trump told Bob Woodward: real power is fear.

It is tempting to think that political fear is largely manufactured – a cynical ploy to manipulate the masses. Trump’s dark vision of the United States would seem to be a prime example of this. Yet, fear can be fitting in politics. Citizens face real dangers from failed political leadership, as lethal to our livelihood as snake bites.

Thomas Hobbes, the 17th-century political philosopher, understood fear.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Scott Aaronson, renowned computer scientist known for his no nonsense take on, well, everything, joins Brian Greene to demystify the state of quantum computation, AI, and much more

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How the Human Brain Contends With the Strangeness of Zero

Yasemin Saplakoglu in Quanta Magazine:

Around 2,500 years ago, Babylonian traders in Mesopotamia impressed two slanted wedges into clay tablets. The shapes represented a placeholder digit, squeezed between others, to distinguish numbers such as 50, 505 and 5,005. An elementary version of the concept of zero was born.

Around 2,500 years ago, Babylonian traders in Mesopotamia impressed two slanted wedges into clay tablets. The shapes represented a placeholder digit, squeezed between others, to distinguish numbers such as 50, 505 and 5,005. An elementary version of the concept of zero was born.

Hundreds of years later, in seventh-century India, zero took on a new identity. No longer a placeholder, the digit acquired a value and found its place on the number line, before 1. Its invention went on to spark historic advances in science and technology. From zero sprang the laws of the universe, number theory and modern mathematics. “Zero is, by many mathematicians, definitely considered one of the greatest — or maybe the greatest — achievement of mankind,” said the neuroscientist Andreas Nieder(opens a new tab), who studies animal and human intelligence at the University of Tübingen in Germany. “It took an eternity until mathematicians finally invented zero as a number.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

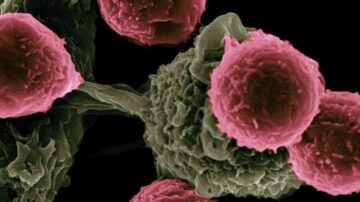

Autoimmune Diseases Stopped in Their Tracks by ‘Phenomenal’ Donor Cell Therapy

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

For the first time, an off-the-shelf CAR T cell therapy has been used to treat potentially life-threatening autoimmune disorders in three people. With a single shot, the treatment rapidly reversed their debilitating symptoms for up to a year. The treatment changed one recipient’s life. Diagnosed with systemic sclerosis—an autoimmune condition that wrecked his muscles and joints—the 57-year-old man, who the study identifies by his last name, Gong, regained his life just two weeks after the injection. He could move the muscles around his mouth to smile. His fingers again danced across a keyboard at work.

For the first time, an off-the-shelf CAR T cell therapy has been used to treat potentially life-threatening autoimmune disorders in three people. With a single shot, the treatment rapidly reversed their debilitating symptoms for up to a year. The treatment changed one recipient’s life. Diagnosed with systemic sclerosis—an autoimmune condition that wrecked his muscles and joints—the 57-year-old man, who the study identifies by his last name, Gong, regained his life just two weeks after the injection. He could move the muscles around his mouth to smile. His fingers again danced across a keyboard at work.

After a year, he told Nature, “I feel very good.”

Gong is part of an ongoing clinical trial to genetically reprogram healthy donor cells into a universal “living drug.” The trial, set to end in 2025, could upend current interventions for untreatable autoimmune disorders. These life-long diseases are mostly managed, but not cured, with immunosuppressant drugs. Though helpful, the medications drastically lower a person’s ability to battle infectious diseases, making it hard to fight off bacterial or viral attacks.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Dua Lipa And George Saunders

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, October 20, 2024

Against False Universals

Seyla Benhabib in Boston Review:

I first arrived in Frankfurt, in this city of immigrants and exiles, in the fall of 1980, as a foreign student and scholar whose life was forever changed by her encounter with it. In Frankfurt I met brilliant friends and scholars from all over the world who gathered in Jürgen Habermas’s “Doktoranden-Kolloquium” on Monday evenings in the old Department of Philosophy on Dantestrasse—alas, a building which no longer exists! In Frankfurt, I also learned about many famous intellectuals whose lives intersected for various periods in this city of migrants, among them none other than Hannah Arendt and Theodor Adorno.

Any consideration of Arendt and Adorno as thinkers who share intellectual affinities is likely to be thwarted from the start by the profound dislike which Arendt in particular seems to have borne towards Adorno. In 1929 Adorno was among members of the faculty of the University of Frankfurt who would be evaluating Arendt’s first husband Günther Anders’s habilitation. Adorno found the work unsatisfactory, thus bringing to an end Anders’s hopes for a university career. It is also in this period that Arendt’s notorious statement regarding Adorno—“Der kommt uns nicht ins Haus,” meaning that Adorno was not to set foot in their apartment in Frankfurt—was uttered.

This hostility on Arendt’s part never diminished, while Adorno encountered it with a cultivated politesse. Arendt’s temper flared up several more times at Adorno: first, when she was wrongly convinced that Adorno and his colleagues were preventing the publication of Walter Benjamin’s posthumous manuscripts, and secondly, when Adorno’s critique of Heidegger—The Jargon of Authenticity—appeared in 1964.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

AMLO’s Surrender

Camilo Ruiz Tassinari in Phenomenal World:

Lopezobradorismo is without a doubt the most significant political movement to have emerged in Mexico over the past three decades. Since 2018, it has reconstituted the country’s post-authoritarian political system. The movement’s new leader, Claudia Sheinbaum won the Presidency with 60 percent of the votes in early June. With a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress, the Movement for National Regeneration (Morena) will have the power to completely rewrite the country’s constitutional compact.

The reach of Morena’s popularity—leading twenty-two out of thirty-two states with its allies—is astounding. For twenty years, Mexican politics was a three way game between the National Action Party (PAN) on the center-right, the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) on the center-left, and a shape-shifting Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) which had ruled the country for most of the twentieth century. During those two decades presidents seldom had a majority in congress and any constitutional change required corrupt bargains between the parties’ grandees. That game is now over: the PRD has practically disappeared, the PRI has hollowed out as most of its leaders moved to Morena, and the PAN has shrunk into a local organization of socially conservative families in the Catholic center-north. Morena has gained more electoral support than any party throughout the country’s quarter century of democracy.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Libby Titus (1947 – 2024) Singer/Songwriter

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why Nobelists Fail

Sanjay G Reddy over at reddytoread:

When I first encountered the ideas central to the winners of this year’s three Nobel Prize in Economics around two and a half decades ago I was startled. The excessive economy of their framework for understanding a complex global reality combined with a set of premises that looked starkly ideological. Despite the time that has passed, the reams that have been written, and the imprimatur these ideas have now received, these charges remain pertinent.

The point of view of the authors remains narrowly focused – even fixated – on property rights, seeing them as defining inclusive economic institutions and as underpinning inclusive political institutions, the coupled concepts at the center of their understanding of Why Nations Fail, the sizable volume in which two of the authors elaborated and extended their view. It is understandable that this perspective enjoys a resonance among property holders and enthusiasts, both in the economic discipline and more broadly in society, as it is reflection of a common sense that prevails in such quarters, but it provides an inadequate guide to understanding either democracy or development. This is because property rights play more diverse and ambivalent roles in both phenomena than they acknowledge. Their view is ahistorical. It misses essential aspects of the colonial experience (such as the impact of ethnic and racial prejudices and solidarities based on the global color line) and its resulting legacies. It also misunderstands the sources of success of rising nations in the contemporary world, such as the role of developmental states.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Coming Second Copernican Revolution

Adam Frank in Noema:

“Today is not your first arrival here.” — Hongzhi Zhengjue, 1091-1157 CE

Across 15,000 generations, human beings have looked out at the sentinel stars and felt the pressing weight of myriad existential questions: Are we alone? Are there other planets also orbiting distant suns? If so, have any of these other worlds also birthed life, or is the drama of our Earth a singular cosmic accident? And what about other minds and civilizations? Have others in the universe, through their success as tool-builders and world-makers, also brought themselves to the brink of collapse?

Across 15,000 generations, human beings have looked out at the sentinel stars and felt the pressing weight of myriad existential questions: Are we alone? Are there other planets also orbiting distant suns? If so, have any of these other worlds also birthed life, or is the drama of our Earth a singular cosmic accident? And what about other minds and civilizations? Have others in the universe, through their success as tool-builders and world-makers, also brought themselves to the brink of collapse?

Remarkably, the first answers to these questions are beginning to arrive. Just as Copernicus reimagined the architecture of our solar system five centuries ago, we are once again in a revolution that pivots on planets. A new science called astrobiology has changed the night sky. It already shows us that nearly every star in the galaxy hosts a family of worlds. Using powerful new instruments and theoretical methods, we’re also learning how to search these distant worlds for alien biospheres. In this way, across the next few decades, we might finally gain answers to the ancient question of our place among life, planets and the cosmos.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

All History Is Environmental History

Ramin Skibba in Undark:

In Amrith’s view, all history is environmental history. And that includes both environmental effects on societies and those societies’ impacts on the environment. He cites evidence, for example, suggesting that a “medieval warm period” spanned most of Europe and parts of North America and western Asia through the 13th century. The period’s benign climate and rainfall, he argues, allowed societies to clear land, expand cultivation, build cities, and grow their populations. He also assesses the rise and fall of the Mongols, who swept across Asia quickly before being thwarted by limited grasses for their horses, intense snowstorms and earthquakes, and deadly plagues that the Mongolian expansion helped spread.

In Amrith’s view, all history is environmental history. And that includes both environmental effects on societies and those societies’ impacts on the environment. He cites evidence, for example, suggesting that a “medieval warm period” spanned most of Europe and parts of North America and western Asia through the 13th century. The period’s benign climate and rainfall, he argues, allowed societies to clear land, expand cultivation, build cities, and grow their populations. He also assesses the rise and fall of the Mongols, who swept across Asia quickly before being thwarted by limited grasses for their horses, intense snowstorms and earthquakes, and deadly plagues that the Mongolian expansion helped spread.

In his analysis, the colonial expansions of the 15th through the early 20th centuries transformed the global distribution of power and wealth while devastating both Indigenous populations and the natural world through deforestation and other ecological harms.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.