Sarah Scoles at Undark:

How autonomous and semi-autonomous technology will operate in the future is up in the air, and the U.S. government will have to decide what limitations to place on its development and use. Those decisions may come sooner rather than later—as the technology advances, global conflicts continue to rage, and other countries are faced with similar choices—meaning that the incoming Trump administration may add to or change existing American policy. But experts say autonomous innovations have the potential to fundamentally change how war is waged: In the future, humans may not be the only arbiters of who lives and dies, with decisions instead in the hands of algorithms.

How autonomous and semi-autonomous technology will operate in the future is up in the air, and the U.S. government will have to decide what limitations to place on its development and use. Those decisions may come sooner rather than later—as the technology advances, global conflicts continue to rage, and other countries are faced with similar choices—meaning that the incoming Trump administration may add to or change existing American policy. But experts say autonomous innovations have the potential to fundamentally change how war is waged: In the future, humans may not be the only arbiters of who lives and dies, with decisions instead in the hands of algorithms.

For some experts, that’s a net-positive: It could reduce casualties and soldiers’ stress. But others claim that it could instead result in more indiscriminate death, with no direct accountability, as well as escalating conflicts between nuclear-armed nations.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

There are paintings that push beyond the confines of their chronology, with auras that have little to do with the orderly genre from which they emerge or even the painters who painted them. Obliterating the frames around them, they break through the fourth wall, headed straight for the viewer’s psyche like a parasite—settling into that part of the mind where we read and recognize ourselves.

There are paintings that push beyond the confines of their chronology, with auras that have little to do with the orderly genre from which they emerge or even the painters who painted them. Obliterating the frames around them, they break through the fourth wall, headed straight for the viewer’s psyche like a parasite—settling into that part of the mind where we read and recognize ourselves. S

S It started, like many good things, as a joke. NBC was filming a preview of its 1984 lineup, and Selma Diamond, a comedian in her sixties, had been tasked with introducing “Miami Vice,” a flashy affair of Ferraris, cocaine cartels, and designer sports jackets. She pretended to misunderstand. “ ‘Miami Nice’?” At last, a show about retirees, with their mink coats and cha-cha lessons. She got a laugh. And some execs thought it might not be a terrible idea.

It started, like many good things, as a joke. NBC was filming a preview of its 1984 lineup, and Selma Diamond, a comedian in her sixties, had been tasked with introducing “Miami Vice,” a flashy affair of Ferraris, cocaine cartels, and designer sports jackets. She pretended to misunderstand. “ ‘Miami Nice’?” At last, a show about retirees, with their mink coats and cha-cha lessons. She got a laugh. And some execs thought it might not be a terrible idea.

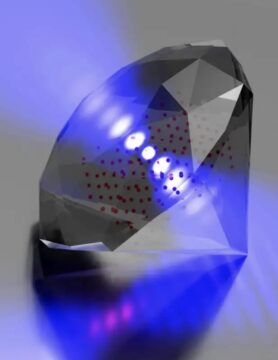

The famous marketing slogan about how a diamond is forever may only be a slight exaggeration for a diamond-based system capable of storing information for millions of years – and now researchers have created one with a record-breaking storage density of 1.85 terabytes per cubic centimetre.

The famous marketing slogan about how a diamond is forever may only be a slight exaggeration for a diamond-based system capable of storing information for millions of years – and now researchers have created one with a record-breaking storage density of 1.85 terabytes per cubic centimetre. Regular Noahpinion readers will know that I’m

Regular Noahpinion readers will know that I’m  I ONCE ASKED Breyten Breytenbach, the exiled South African poet and painter, why, in his opinion, after the fiasco of his clandestine return to his homeland in 1975 (traveling incognito as a would-be revolutionary organizer), the calamity of his arrest (his cover having likely been blown before he even entered the country, such that not only was he arrested but virtually everyone he’d contacted was arrested as well), the debacle of his trial (his appalling, groveling breakdown, his operatic recantations and expressions of contrition, all to no avail), after his being sentenced to nine years’ hard time in the country’s notorious penal system, why, I asked him, why had the authorities who allowed him to go on writing in prison nevertheless forbidden him to paint?

I ONCE ASKED Breyten Breytenbach, the exiled South African poet and painter, why, in his opinion, after the fiasco of his clandestine return to his homeland in 1975 (traveling incognito as a would-be revolutionary organizer), the calamity of his arrest (his cover having likely been blown before he even entered the country, such that not only was he arrested but virtually everyone he’d contacted was arrested as well), the debacle of his trial (his appalling, groveling breakdown, his operatic recantations and expressions of contrition, all to no avail), after his being sentenced to nine years’ hard time in the country’s notorious penal system, why, I asked him, why had the authorities who allowed him to go on writing in prison nevertheless forbidden him to paint? Dreams can transport us anywhere—from soaring above treetops to reliving the grind of office life—but what do they truly reveal? A recent survey by Talker Research for Newsweek asked 1,000 U.S. adults about their most

Dreams can transport us anywhere—from soaring above treetops to reliving the grind of office life—but what do they truly reveal? A recent survey by Talker Research for Newsweek asked 1,000 U.S. adults about their most  Students, colleagues, and friends all saw how seriously Edward Said took clothes. “Our usual ritual upon meeting after some time apart,” a friend remembers, “was for him to look me up and down and pass withering judgments on the condition of my shoes, and to berate my obstinate reluctance to engage a proper tailor.” Said insisted another friend, a colleague at Columbia University, buy a jacket he “didn’t need (and couldn’t afford) . . .. but I couldn’t withstand the force of Edward’s solicitude, and finally went and bought one. Black. Cashmere. Very nice. I wore it for ages.” In all these accounts, Said’s clothes set him apart. “[O]ne of the features that distinguished him from the rest of us,” a fellow seminar participant recalls, “was his immaculate dress sense: everything was meticulously chosen, down to the socks. It is almost impossible to visualize him any other way.”

Students, colleagues, and friends all saw how seriously Edward Said took clothes. “Our usual ritual upon meeting after some time apart,” a friend remembers, “was for him to look me up and down and pass withering judgments on the condition of my shoes, and to berate my obstinate reluctance to engage a proper tailor.” Said insisted another friend, a colleague at Columbia University, buy a jacket he “didn’t need (and couldn’t afford) . . .. but I couldn’t withstand the force of Edward’s solicitude, and finally went and bought one. Black. Cashmere. Very nice. I wore it for ages.” In all these accounts, Said’s clothes set him apart. “[O]ne of the features that distinguished him from the rest of us,” a fellow seminar participant recalls, “was his immaculate dress sense: everything was meticulously chosen, down to the socks. It is almost impossible to visualize him any other way.” Not too long ago, Brad Pitt and Eric Bana starred in a (loose)

Not too long ago, Brad Pitt and Eric Bana starred in a (loose)