Bruce Robbins at The Baffler:

Did the novels of the twentieth century accomplish anything? Edwin Frank, who is known for his love of the genre, is convinced they did. In his stylish, selective survey Stranger Than Fiction: Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel, he focuses on the genre’s formal innovations, which take readers’ minds off their somewhat vulgar appetite for suspenseful plot and relatable character and teach them to be satisfied, instead, with something like a diet of single sentences, exquisitely prepared. The genre’s masterworks urge us to set a slower pace, savoring what each novelist puts on the table and realizing, as we push back our chairs, how much more substantial the meal was than what we thought we wanted.

There is both instruction and pleasure to be had from Frank’s commentaries on modernist sentence-making. In German, as he notes, the run-on sentence doesn’t violate any rules, but Kafka takes the run-on and runs away with it, adding “slight nervous shifts of tone and implication, abrupt introductions of unforeseen elements that are then absorbed without comment, as if expected.” This procedure makes these sentences “an endless surprise, entertaining disconcerting, effortless, tortured, suddenly funny, and wonderfully sad.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

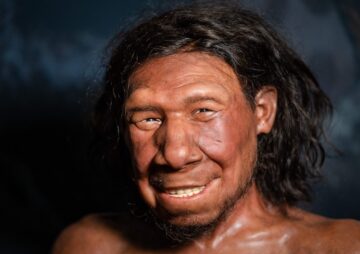

Do you find it easy to wake up early? You may have Neanderthals in your ancestry.

Do you find it easy to wake up early? You may have Neanderthals in your ancestry.

Now it was June, and we were at the National Hot Rod Association’s Nostalgia Nationals at Beech Bend Raceway in Bowling Green, Kentucky. The weather was brutal, and it was forecast to remain so: sunny, low to mid-nineties, wiltingly humid. In the distance, an antique roller coaster creaked along wooden tracks, and I wondered who would choose to ride it when there were so many cars to ogle and races to watch and people to meet.

Now it was June, and we were at the National Hot Rod Association’s Nostalgia Nationals at Beech Bend Raceway in Bowling Green, Kentucky. The weather was brutal, and it was forecast to remain so: sunny, low to mid-nineties, wiltingly humid. In the distance, an antique roller coaster creaked along wooden tracks, and I wondered who would choose to ride it when there were so many cars to ogle and races to watch and people to meet. Like the writing of book reviews, the live author interview has been placed under the sign of “marketing and publicity,” and treated less as a distinct skill than part of an ethos of service—something that “professional” writers do for other writers and for their publishers—as well as signaling everyone’s support for the perennially endangered small bookstores and event spaces that host them. The assumption is that the interviewer, like the interviewee, has something to sell. Since everyone is engaged in promotion, no one has to be paid. The sense that the interview is a devalued form, anyone can do it, especially if they published a book a year before the book under discussion, makes it a kind of professional corvée for writers whose value accrues elsewhere. This can often have a corrosive effect on the quality of the events. I have been to evenings where it appears the interviewer hasn’t even read the author’s book. More recently they have become another opportunity to indulge in guilty feelings and remind everyone in attendance that something more important and painful is happening elsewhere. In general, people come to these things to look rather than to listen and they do them to be seen rather than heard. The author will be signing books afterwards; there will be free drinks before you go out to pay for drinks; you can take a selfie if you want.

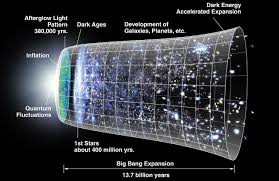

Like the writing of book reviews, the live author interview has been placed under the sign of “marketing and publicity,” and treated less as a distinct skill than part of an ethos of service—something that “professional” writers do for other writers and for their publishers—as well as signaling everyone’s support for the perennially endangered small bookstores and event spaces that host them. The assumption is that the interviewer, like the interviewee, has something to sell. Since everyone is engaged in promotion, no one has to be paid. The sense that the interview is a devalued form, anyone can do it, especially if they published a book a year before the book under discussion, makes it a kind of professional corvée for writers whose value accrues elsewhere. This can often have a corrosive effect on the quality of the events. I have been to evenings where it appears the interviewer hasn’t even read the author’s book. More recently they have become another opportunity to indulge in guilty feelings and remind everyone in attendance that something more important and painful is happening elsewhere. In general, people come to these things to look rather than to listen and they do them to be seen rather than heard. The author will be signing books afterwards; there will be free drinks before you go out to pay for drinks; you can take a selfie if you want. The number of neurons in the human brain is comparable to the number of stars in the Milky Way galaxy. Unlike the stars, however, in the case of neurons the real action is in how they are directly connected to each other: receiving signals over synapses via their dendrites, and when appropriately triggered, sending signals down the axon to other neurons (glossing over some complications). So a major step in understanding the brain is to map its wiring diagram, or

The number of neurons in the human brain is comparable to the number of stars in the Milky Way galaxy. Unlike the stars, however, in the case of neurons the real action is in how they are directly connected to each other: receiving signals over synapses via their dendrites, and when appropriately triggered, sending signals down the axon to other neurons (glossing over some complications). So a major step in understanding the brain is to map its wiring diagram, or

In 2016, an essay arrived in our offices from John J. Lennon, then incarcerated at Attica Correctional Facility in New York. “

In 2016, an essay arrived in our offices from John J. Lennon, then incarcerated at Attica Correctional Facility in New York. “ Jaime Teevan joined

Jaime Teevan joined

Trump’s political rebirth is unparalleled in American history. His first term ended in disgrace, with his attempts to overturn the 2020 election results culminating in the attack on the U.S. Capitol. He was shunned by most party officials when he announced his candidacy in late 2022 amid multiple criminal investigations. Little more than a year later, Trump cleared the Republican field, clinching one of the fastest contested presidential primaries in history. He spent six weeks during the general election in a New York City courtroom, the first former President to be

Trump’s political rebirth is unparalleled in American history. His first term ended in disgrace, with his attempts to overturn the 2020 election results culminating in the attack on the U.S. Capitol. He was shunned by most party officials when he announced his candidacy in late 2022 amid multiple criminal investigations. Little more than a year later, Trump cleared the Republican field, clinching one of the fastest contested presidential primaries in history. He spent six weeks during the general election in a New York City courtroom, the first former President to be  Annie Rauwerda: I started back in high school editing typos and adding things that I noticed were missing — like items to lists. But I had never done anything more than that because I was afraid of it because there are so many rules. Like, I’d seen the talk pages. And many of Wikipedia’s policies and guidelines and essays are very wordy.

Annie Rauwerda: I started back in high school editing typos and adding things that I noticed were missing — like items to lists. But I had never done anything more than that because I was afraid of it because there are so many rules. Like, I’d seen the talk pages. And many of Wikipedia’s policies and guidelines and essays are very wordy. An optical fibre technology can help chips communicate with each other at the speed of light, enabling them to transmit 80 times as much information as they could using traditional electrical connections. That could significantly speed up the training times required for large artificial intelligence models – from months to weeks – while also reducing the energy and emissions costs for data centres.

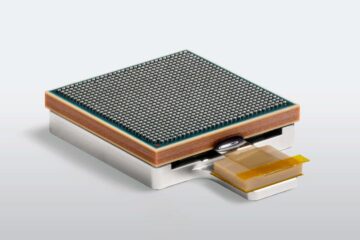

An optical fibre technology can help chips communicate with each other at the speed of light, enabling them to transmit 80 times as much information as they could using traditional electrical connections. That could significantly speed up the training times required for large artificial intelligence models – from months to weeks – while also reducing the energy and emissions costs for data centres. In the fall of 2012, when Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the military power now in charge of Syria, was a mere minor terrorist organization, a band of their fighters in Aleppo took me prisoner. Back then they were known as Jabhat al-Nusra. I remained in the group’s custody for two years—often in solitary confinement cells, but not always. During this time, it often happened that news of some stupendous victory would make its way, via the fighters’ two-way radios, into our prisons. It was a surreal experience then to listen as a government checkpoint got blown into the sky, for instance, or a truckload of government troops fell into my captors’ hands.

In the fall of 2012, when Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the military power now in charge of Syria, was a mere minor terrorist organization, a band of their fighters in Aleppo took me prisoner. Back then they were known as Jabhat al-Nusra. I remained in the group’s custody for two years—often in solitary confinement cells, but not always. During this time, it often happened that news of some stupendous victory would make its way, via the fighters’ two-way radios, into our prisons. It was a surreal experience then to listen as a government checkpoint got blown into the sky, for instance, or a truckload of government troops fell into my captors’ hands. The thing that had precipitated Warner into the literary limelight, and earned her quite a lot of money, was her novel of 1926, Lolly Willowes. As an assertion of female autonomy and idiosyncrasy, it was both timely and captivating. It was also prescient, with its theme of decamping to the country about to be enacted in the life of its author (though perhaps without so sorcerous a resolution). Laura (Lolly) Willowes is a wry old-maidish lady occupying a rather put-upon role in the London household of her married brother, when she suddenly takes flight to a hamlet in the Chilterns called Great Mop, enters into a compact with the Devil and becomes a witch. Despite its subject matter, the book is not excessively whimsical – or its whimsey is tempered by a stern ironic overtone. A style at once mischievous and elegant is one of Warner’s hallmarks, whether it’s applied to a mediaeval nunnery beset by money worries (The Corner That Held Them, 1948), the beguiling and ruthless Cat’s Cradle Book (1960), or the distinctly unfairylike Kingdoms of Elfin (1977), her last subversive flight-of-fancy, carried out with an eldritch inventiveness.

The thing that had precipitated Warner into the literary limelight, and earned her quite a lot of money, was her novel of 1926, Lolly Willowes. As an assertion of female autonomy and idiosyncrasy, it was both timely and captivating. It was also prescient, with its theme of decamping to the country about to be enacted in the life of its author (though perhaps without so sorcerous a resolution). Laura (Lolly) Willowes is a wry old-maidish lady occupying a rather put-upon role in the London household of her married brother, when she suddenly takes flight to a hamlet in the Chilterns called Great Mop, enters into a compact with the Devil and becomes a witch. Despite its subject matter, the book is not excessively whimsical – or its whimsey is tempered by a stern ironic overtone. A style at once mischievous and elegant is one of Warner’s hallmarks, whether it’s applied to a mediaeval nunnery beset by money worries (The Corner That Held Them, 1948), the beguiling and ruthless Cat’s Cradle Book (1960), or the distinctly unfairylike Kingdoms of Elfin (1977), her last subversive flight-of-fancy, carried out with an eldritch inventiveness. A

A Nicole Kidman’s eyes widened. “Haven’t you been to the Rockettes?” she asked. “I go every year. Oh yeah, I’m obsessed!”

Nicole Kidman’s eyes widened. “Haven’t you been to the Rockettes?” she asked. “I go every year. Oh yeah, I’m obsessed!”