Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

On Mona Chollet And The Limits of Comparative Feminism

Hannah Felt Garner at The Millions:

Though it’s not presented as such in her introduction or conclusion, femicide, as the ne plus ultra of patriarchal logic, is at the core of Chollet’s analysis in Reinventing Love. In a chapter entitled “Real Men,” Chollet argues that intimate partner violence should be thought of not as an aberration but rather as the most logical outcome of gender norms. She quotes feminist therapist Elisende Coladan in suggesting that, instead of calling abusive partners “narcissists,” such men should more readily be called the “healthy children of patriarchy.” Taking this logic further, Chollet spends a large chunk of this chapter analyzing with great curiosity what’s going on with the women who fall in love with known serial killers, from Shirlee Book, who married the 1970s serial rapist, torturer, and strangler Kenneth Bianchi, to the dozens of young women who came out in support of Ted Bundy during his trial. While it may be tempting to dismiss these women as lunatics, she writes, “we may also wonder if the killers and their groupies are simply pushing to the limit the usual gender roles that in smaller doses constitute our everyday reality. If virility is linked to strength, to domination, to the exercise of violence, then what could be more virile than an assassin?”

Though it’s not presented as such in her introduction or conclusion, femicide, as the ne plus ultra of patriarchal logic, is at the core of Chollet’s analysis in Reinventing Love. In a chapter entitled “Real Men,” Chollet argues that intimate partner violence should be thought of not as an aberration but rather as the most logical outcome of gender norms. She quotes feminist therapist Elisende Coladan in suggesting that, instead of calling abusive partners “narcissists,” such men should more readily be called the “healthy children of patriarchy.” Taking this logic further, Chollet spends a large chunk of this chapter analyzing with great curiosity what’s going on with the women who fall in love with known serial killers, from Shirlee Book, who married the 1970s serial rapist, torturer, and strangler Kenneth Bianchi, to the dozens of young women who came out in support of Ted Bundy during his trial. While it may be tempting to dismiss these women as lunatics, she writes, “we may also wonder if the killers and their groupies are simply pushing to the limit the usual gender roles that in smaller doses constitute our everyday reality. If virility is linked to strength, to domination, to the exercise of violence, then what could be more virile than an assassin?”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, December 15, 2024

Nikki Giovanni (1943 – 2024) Poet And Writer

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

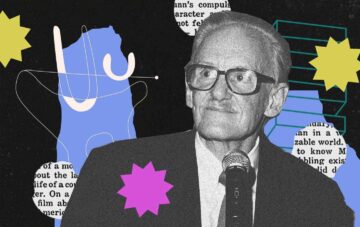

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

Zachary Fine in The Nation:

It can be argued, with some important caveats and qualifications, that Peter Schjeldahl was the most inventive, entertaining, and self-observing art critic to have ever worked in the English language. For 60 years, give or take, he struck himself like a tuning fork against works of art and attempted to transcribe the way his nerves vibrated to the aesthetic. These transcriptions involved dense, epigrammatic sentences, zany metaphors, and a chatty authority that was both deceptively approachable and disarmingly smart. Although he put himself in the bloodline of poet-critics like Baudelaire and Frank O’Hara, their prose never approaches anything like the constant, look-at-me lexical wizardry of an exhibition review by Schjeldahl. His writing credo: “Concentrated. At least one idea per sentence. Melodious, I hope. With jokes.”

It can be argued, with some important caveats and qualifications, that Peter Schjeldahl was the most inventive, entertaining, and self-observing art critic to have ever worked in the English language. For 60 years, give or take, he struck himself like a tuning fork against works of art and attempted to transcribe the way his nerves vibrated to the aesthetic. These transcriptions involved dense, epigrammatic sentences, zany metaphors, and a chatty authority that was both deceptively approachable and disarmingly smart. Although he put himself in the bloodline of poet-critics like Baudelaire and Frank O’Hara, their prose never approaches anything like the constant, look-at-me lexical wizardry of an exhibition review by Schjeldahl. His writing credo: “Concentrated. At least one idea per sentence. Melodious, I hope. With jokes.”

From his early pieces in ARTnews in the 1960s to his final review in The New Yorker in 2022, Schjeldahl’s career spanned from Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and Andy Warhol’s golden years to Bidenomics and Beeple, with only one brief interruption in the mid-1970s—when he tried to quit art criticism and get back to poetry (his true love), but realized “there was nothing else that I did very well that they pay you for.” Having a career that lasts over half a century is not unusual, but being an art critic for that long definitely is. An art critic must endure (or enjoy) the constant grind of gallery-going and press junkets, an oppressively swampy environment of mega-wealth and self-congratulation, and the never-ending churn of the “new.” It’s also a job that easily corrupts, as Schjeldahl discovered—gallerists try to buy you, artists try to sleep with you—and like many writers, critics have a talent for alienating friends and family (as Schjeldahl did), falling prey to substance abuse and addiction (as Schjeldahl did), and seesawing between narcissism and self-loathing (as Schjeldahl did). He was also, to the dismay of his family, prone to breakfasts of bacon and Entenmann’s chocolate donuts, negligent in matters of dental hygiene, and a lifelong smoker—typically three packs a day.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Seven Deadly Sins – the biology of human frailty

Philip Ball in The Guardian:

‘From Adam has sprung one mass of sinners and godless men,” wrote St Augustine, arguably the key architect of the Christian doctrine of original sin. The notion that babies are born with this indelible stain, the residue of Adam’s fall in Eden, can seem one of the most pernicious features of Christian dogma. But as Guy Leschziner argues in Seven Deadly Sins, we could interpret Augustine’s austere judgment as an acknowledgment that we are inherently inclined to do things we shouldn’t. The catalogue of seven direst vices first adduced by Tertullian and immortalised in Dante’s Divine Comedy – pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust, gluttony and sloth – may seem arbitrary, but we can all recognise aspects of them in ourselves.

‘From Adam has sprung one mass of sinners and godless men,” wrote St Augustine, arguably the key architect of the Christian doctrine of original sin. The notion that babies are born with this indelible stain, the residue of Adam’s fall in Eden, can seem one of the most pernicious features of Christian dogma. But as Guy Leschziner argues in Seven Deadly Sins, we could interpret Augustine’s austere judgment as an acknowledgment that we are inherently inclined to do things we shouldn’t. The catalogue of seven direst vices first adduced by Tertullian and immortalised in Dante’s Divine Comedy – pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust, gluttony and sloth – may seem arbitrary, but we can all recognise aspects of them in ourselves.

Leschziner, a consultant neurologist at Guy’s Hospital in London, explores the physiological and psychological roots of these “failings” and argues that, in mild degree, all might be considered not just universal but necessary human attributes. The goal, he implies, is not to renounce them but to align our natural impulses with the demands of living healthily and productively in society. Seven Deadly Sins takes the case-study format pioneered by Oliver Sacks in using dysfunction to explore the neurological origins of behaviour. It is a profoundly humane book, occasionally compromised by excessive clinical detail and perhaps more so by its lack of wider context.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Amazing Kreskin (1935 – 2024) Mentalist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

There Was a Time

There was a time

when Time evoked tomorrows.

Today, it speaks only of yesterdays.

Where has the promise gone

of fraternité sans frontières?

Where are the tears we shed,

the blood to irrigate an earth,

once yours, now mine,

once mine, now yours?

Why must my only view

of you be through

the barrel of a gun?

Why must I search for you

in the debris of a divided sun?

How long will this daily suicide last?

Will we have separate heavens there, as well,

or find ourselves sharing

another common hell?

by F.S. Aijazuddin

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Martial Solal (1927 – 2024) Jazz Pianist and Composer

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Erdoğan’s Syria?

Cihan Tuğal in Sidecar:

Turkish pro-government circles are euphoric – not only because an Islamist-led coalition toppled the dictator they detested, but also because they believe that their president orchestrated the whole operation. In the earliest days of the Arab Spring, the AKP’s calculation was that the uprisings would produce a few governments that would adopt the ‘Turkish model’, combining conservative religion, formal democracy and neoliberal governance. Syria’s Islamists appeared to fit the bill. Yet after Assad’s violent crackdown against civilian protests made such a transition impossible, Turkey began to arm a series of rebel militias, joining Western powers, Russia and Iran in a race to militarize and sectarianize the conflict. This resulted in a de facto partitioning of the country into separate Shia, Sunni and Kurdish regions. At least four million Syrians crossed into Turkey, fueling anti-immigrant sentiment there. The stalemate appeared to be endless, until Islamist-led forces finally captured Damascus last week.

Since then, Islamist newspapers have hailed Erdoğan as the commander of the ‘Syrian Revolution’, ‘the Conqueror of Syria’ and ‘the greatest revolutionary of the 21st century’. While some on the Turkish right had begun to doubt the government’s Syria policy, holding it responsible for the refugee crisis, now the Erdoğanists seem vindicated. With Assad toppled, they are expecting both a domestic reconsolidation of power around the ruling AKP and a massive increase in Turkish influence across the region – with many announcing the effective end of Western control.

The opposition, by contrast, views the fall of Assad as the outcome of an American game in which Erdoğan and the jihadis were pawns.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Return of the Future and the Last Man

Carlos Bravo Regidor interviews Ivan Krastev in The Ideas Letter:

Carlos Bravo Regidor: The year 2024 is coming to an end and it might be fitting to kick off this conversation by asking you about its significance—not necessarily in terms of what is to follow, but rather in terms of what has happened and what it means retrospectively. How would you assess 2024 in light of where we were coming from and where it leaves us?

Ivan Krastev: 2024 is certainly going to be remembered as a turning point. When the year started, everybody was pointing at its unusual combination of wars and elections. And there was this sense of change, of something ending and something else starting, and that was felt everywhere. But the strongest sign of the fact that we’re living in a moment of radical change is not what we’re discussing about the future; it’s what we’re discussing about the past. If you look at 2024 and you go back to the debates about what happened in, for example,1989, you’ll see how different that conversation is today. Because, in a certain way, it’s not simply about this cliché that the post–Cold War world was ending: It’s more about how we’ve realized there was always something about it, something more, that we weren’t ready to see. And now we are.

Today we see 1989 as something more than the fall of the Berlin Wall; it was about the massacre at Tiananmen Square, too. So, it meant not only the end of communism in Europe, but also the resilience of communism in China, which has turned out to be quite important, perhaps even more important, historically. And 1989 was significant for radical Islam: It was that year that for the first time an Islamist country defeated a superpower. In fact, a 2019 survey conducted by the Levada Center, an independent pollster, asked Russians what was for them the most important thing that happened in 1989, and most answered not elections in Poland, not Tiananmen, not the Berlin Wall, but the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan. That wasn’t about the end of communism; it was about Moscow losing its superpower mystique.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Political Investments

Andrew Yamakawa Elrod and Tim Barker interview Thomas Ferguson in Phenomenal World:

Andrew elrod: One thing that struck me about the 2024 election, and really about Democratic strategy since the 2022 midterms, was the degree to which the party seemed to be engineering a demobilizing operation.

Thomas ferguson: Let’s put it in very simple English. Joe Biden was the consensus candidate of the Democratic Party establishment in 2020 because he was the only one who was broadly acceptable within the Party, looked viable against Trump, and could hold off Sanders. His candidacy was strongly reminiscent of Paul von Hindenburg’s second run for president in the last days of the Weimar Republic, when everyone from liberal elements of big business to the Social Democrats united around the doddering octogenarian as the only candidate capable of defeating Hitler.

I like to start the discussion of recent American politics with the 2014 midterm elections, which I analyzed in a piece with Walter Dean Burnham. The big story in 2014 was the stupendous decline in voting turnout compared to the presidential election in 2012. The turnout drop off was the second largest ever in percentage terms. Only the 1942 decline was greater, because millions of voters were shipping out across the globe to serve in World War II. But in many states turnout in 2014 collapsed to astonishingly low levels, akin to those of the Federalist era (when property suffrage laws limited voting).

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, December 13, 2024

Reasons to be Cheerful with David Byrne

NPR’s Scott Simon sat down with David Byrne five years after the legendary musician, artist and former Talking Heads frontman launched a nonprofit online magazine called Reasons to be Cheerful. The magazine offers good news in a market otherwise dominated by doom and gloom. In this episode, Byrne discusses the origins of Reasons to be Cheerful, the stories that have stuck with him, and his personal reflections on cheer in our world today.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Silurian Hypothesis: It was the Cephalopods

Klaus M. Stiefel at his own website:

A hypothesis called “The Silurian hypothesis” wins the title of “most interesting hypothesis most likely to be false” for all of science. In brief, the hypothesis postulates that previously a species different from ours had achieved high intelligence and technological civilization on this planet. The Silurian hypothesis (named after “Silurian” aliens in the brainy British TV series “Doctor Who”) was initially proposed by two astronomers, Gavin A. Schmidt and Adam Frank, as a thought experiment, to see if it would even be feasible to detect the traces of such a hypothetical civilization which had existed many millions of years ago. Would there still be detectable changes in the sedimentation patterns if someone (not human) had built cities and military bases a hundred million years ago? Would ancient trash dumps be conserved somewhere, somehow? Would there be changes in the patterns of radioisotopes in the rocks as a result of an ancient nuclear war?

A hypothesis called “The Silurian hypothesis” wins the title of “most interesting hypothesis most likely to be false” for all of science. In brief, the hypothesis postulates that previously a species different from ours had achieved high intelligence and technological civilization on this planet. The Silurian hypothesis (named after “Silurian” aliens in the brainy British TV series “Doctor Who”) was initially proposed by two astronomers, Gavin A. Schmidt and Adam Frank, as a thought experiment, to see if it would even be feasible to detect the traces of such a hypothetical civilization which had existed many millions of years ago. Would there still be detectable changes in the sedimentation patterns if someone (not human) had built cities and military bases a hundred million years ago? Would ancient trash dumps be conserved somewhere, somehow? Would there be changes in the patterns of radioisotopes in the rocks as a result of an ancient nuclear war?

So, in their original paper, Schmidt & Frank didn’t actually voice belief in an ancient civilization, but pondered the question if and how it would be detectable. They conclude that no ruins of ancient football stadiums, highways or housing projects would survive geological time. In contrast, unusual episodes of global warming and the presence of certain artificial radioisotopes (Plutonium-244 and Curium-247) would give an ancient civilization away. Mass extinctions could be a sign of an ancient smart, technological, fast-expanding species.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Large drones have been spotted flying over the US for weeks, and state and federal officials say they still have no idea who is behind the flights

Jeremy Hsu in New Scientist:

Mysterious drones have been swarming the night skies above New Jersey and other nearby states for a month. They have been spotted over several US military sites. They have been videoed over houses and apartment buildings. A swarm was seen following a US Coast Guard rescue boat at the same time that New Jersey police reported 50 drones arriving on land from the ocean. But no one seems to know who is piloting them, or whether it is a coordinated effort.

Mysterious drones have been swarming the night skies above New Jersey and other nearby states for a month. They have been spotted over several US military sites. They have been videoed over houses and apartment buildings. A swarm was seen following a US Coast Guard rescue boat at the same time that New Jersey police reported 50 drones arriving on land from the ocean. But no one seems to know who is piloting them, or whether it is a coordinated effort.

The incidents have drawn the attention of state governors and legislators, as well as members of the US Congress, and the FBI has launched an investigation, asking for the public to report sightings.

Witnesses describe the drones as being as loud as lawnmowers, with some approaching the size of a small car – significantly larger than a typical quadcopter or multirotor drone that anyone can purchase.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Watch this bird-inspired drone leap into the air

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Liberalism and the Non-European: Isaiah Berlin and Edward Said

Beatriz Silva in the Journal of the History of Ideas blog:

“November is a mournful month in the history of Palestine,” Edward Said began his eulogy in memory of Sir Isaiah Berlin in 1997. With the news of Berlin’s passing came an outpour of newspaper articles written by the philosopher’s admirers, friends, and scholars, honoring the man who remains one of the major liberal thinkers of the Cold War. Said’s text, published in the pan-Arab newspaper Al-Hayat, went relatively unnoticed. In the first few paragraphs, the Columbia University professor remembers a man with whom he shared intellectual roots: a skilled orator and a philosopher with an astonishing breadth of knowledge that extended well beyond philosophy. The second part of the text takes an introspective turn, as Said confesses to the reader: “None of us [Palestinians]—and I do not excuse myself at all were able to engage with Berlin on the question of Palestine.” With this reflection, Said hints at an aspect of Berlinian scholarship that persists inadequately addressed: the British philosopher’s unwavering commitment to the state of Israel and, most importantly, his dismissal of the experiences of Palestinians since 1948. In highlighting what has tended to be written off as a mere footnote in Berlin’s life, Said suggests a re-evaluation of the Oxford don’s liberal theory by asking: who was Isaiah Berlin’s liberalism for?

“November is a mournful month in the history of Palestine,” Edward Said began his eulogy in memory of Sir Isaiah Berlin in 1997. With the news of Berlin’s passing came an outpour of newspaper articles written by the philosopher’s admirers, friends, and scholars, honoring the man who remains one of the major liberal thinkers of the Cold War. Said’s text, published in the pan-Arab newspaper Al-Hayat, went relatively unnoticed. In the first few paragraphs, the Columbia University professor remembers a man with whom he shared intellectual roots: a skilled orator and a philosopher with an astonishing breadth of knowledge that extended well beyond philosophy. The second part of the text takes an introspective turn, as Said confesses to the reader: “None of us [Palestinians]—and I do not excuse myself at all were able to engage with Berlin on the question of Palestine.” With this reflection, Said hints at an aspect of Berlinian scholarship that persists inadequately addressed: the British philosopher’s unwavering commitment to the state of Israel and, most importantly, his dismissal of the experiences of Palestinians since 1948. In highlighting what has tended to be written off as a mere footnote in Berlin’s life, Said suggests a re-evaluation of the Oxford don’s liberal theory by asking: who was Isaiah Berlin’s liberalism for?

The two intellectuals met for the last time at a London restaurant in 1996. “Unfailingly cordial,” as Said described Berlin’s treatment of himself, “he called out to me and insisted on chatting briefly with me about the eighteenth-century Italian philosopher Vico.” Berlin and Said’s shared interest in Giambattista Vico indicates that the two academics shared more in common than one might expect.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Brady Corbet’s Outsider American Epic

Alexandra Schwartz at The New Yorker:

“Cinema is frequently associated with glamour, but the reality is that it’s labor,” Corbet told me. In the case of “The Brutalist,” his work seemed to be paying off. Initial reactions had been ecstatic. At Venice, where the film premièred, in early September, viewers had applauded for somewhere between twelve minutes (according to Variety) and thirteen minutes and five seconds (according to Deadline), longer than for any other festival entry but Pedro Almodóvar’s, and Corbet won the Silver Lion for Best Director. The film, which will be released in late December, was already being discussed as a Best Picture contender, and Brody as a Best Actor front-runner. (This week, it was nominated for both awards, plus five more, by the Golden Globes.)

“Cinema is frequently associated with glamour, but the reality is that it’s labor,” Corbet told me. In the case of “The Brutalist,” his work seemed to be paying off. Initial reactions had been ecstatic. At Venice, where the film premièred, in early September, viewers had applauded for somewhere between twelve minutes (according to Variety) and thirteen minutes and five seconds (according to Deadline), longer than for any other festival entry but Pedro Almodóvar’s, and Corbet won the Silver Lion for Best Director. The film, which will be released in late December, was already being discussed as a Best Picture contender, and Brody as a Best Actor front-runner. (This week, it was nominated for both awards, plus five more, by the Golden Globes.)

Corbet found the swell of advance enthusiasm gratifying, if bewildering. “Historically, if something is really radical, people initially don’t like it,” he said. “What’s very unusual about ‘The Brutalist’ is that people are connecting with it much faster than I expected them to. I’m very touched, but I’m also completely confused.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Brady Corbet And Others On The Brutalist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

Shoulders Are For Emergencies Only

Talk to me, Poem . . . I’m all alone . . . Nobody understands what

I’m saying . . .

Have you been in jail, Poem . . . A lot of poems go to jail . . . like

a lot of women who get tired of no-good men . . . Do-no-good-

poems beat up on people . . . Do-no-good-poems say I’m sorry the

next day . . .

I know poems get lost . . . because they’re always being found . . .

There are Wanted posters . . . milk bottles . . . and lonesome

guitars in the night . . . looking for a poem to take home . . .

I know poems get neglected . . . just like doo-wop singing on the

back porch and the deacons opening church with Leaning on the

Everlasting Arms . . . people forget what got them over . . . what

saved them

What are your plans, Poem . . . Give it up . . . I hear you’re a rap

star now . . . going for the Grammy and the gold . . . everybody

singing your praises . . .Do you ever miss your home . . .

The sign on I-81 says: Shoulders Are For Emergencies Only . . .

Ride me, Poem . . . I think I’ve got the blues . . .

by Nikki Giovanni

from Quilting the Black-Eyed Pea

Harper Perennial, 2002

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Funny Compliments That’ll Win Everyone Over

Charlotte Andersen in Reader’s Digest:

The chance of meeting a person like you is the only reason I talk to strangers.

The chance of meeting a person like you is the only reason I talk to strangers.

- Being friends with you is like peeing my pants: warm, a relief and something the whole world will eventually see.

- You inspire me! Not enough to cure cancer but enough to load the dishwasher. And the dishwasher is definitely my most pressing problem.

- You’re the only one I let control the music when I drive.

- No one understands me like you do—not even me.

- You’re so efficient, you can cook Minute rice in 30 seconds.

- I saved a sample of your DNA … just in case cloning ever becomes legal.

- I brag to all my friends about you.

- I love your weird so much, it has become my normal.

- Thanks for inviting me over. You’ve got a real nice joint here—your elbow, specifically.

- You’re my rock when I hit rock bottom. Thanks for softening the fall.

- One of my favorite hobbies is hanging out with smart people. I got into it after I met you.

- Whenever I’m upset, you’re the first person I want to talk to … which probably sucks for you, but you handle it like a champ!

- You’re the only person who understands my sign language when I’m crying.

- Confession: You make me laugh so hard I pee a little.

- Are we bad at being good or just really good at being bad? Not that it matters.

- I love you like waffles love Nutella.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.