There is no escape from the angst outside

but the world within; find it. — Roshi Bob

Hiding Places

There are hiding places in my room

where beautiful poems are hidden

Poems hidden away in boxes

on sheets of brown paper

Poems of spirit and magic

workers hands hidden in boxes

beautiful thighs

there are blue skies hidden in my room

dolphins and seagulls

the heaving of breasts and oceans

there are skies in my room

there are flies in my room

there are streets in my room

there are a thousand nights hidden in boxes

there are drunks in my poems

there are a million stars on the roof of my room

all hidden away in boxes

there are steps down side streets

there is a crazed eye of a poet in my room

there are old Arabs exploring the desert near Escalon

there are sparrows and bluebirds and wildcats in my room

there are elephants and tigers

there are skinny Italian girls in my room

there are letters from Peru and England

and Germany and Russia in my room

There are the steps of Odessa in my room

the Volga river in my room

there are dreams in the night of my room

there are flowers

there is the dance of affirmation in my room

the steps of young poets carrying knapsacks full of poems

there are the Pictures of an Exhibition in my room

Moussorgsky and Shostakovich

and Charlie Mingus in my room

Composers and painters all singing in my room

all hidden away in boxes

one night when the moon is full

they will come out and do a dance

by Jack Micheline

from Poetic Outlaws

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Electing Donald J. Trump once could be dismissed as a fluke, an aberration, a terrible mistake—a consequential one, to be sure, yet still fundamentally an error. But America has now twice elected him as its President. It is a disastrous revelation about what the United States really is, as opposed to the country that so many hoped that it could be. His victory was a worst-case scenario—that a convicted felon, a chronic liar who mismanaged a deadly once-in-a-century pandemic, who tried to overturn the last election and unleashed a violent mob on the nation’s Capitol, who calls America “a garbage can for the world,” and who threatens retribution against his political enemies could win—and yet, in the early morning hours of Wednesday, it happened.

Electing Donald J. Trump once could be dismissed as a fluke, an aberration, a terrible mistake—a consequential one, to be sure, yet still fundamentally an error. But America has now twice elected him as its President. It is a disastrous revelation about what the United States really is, as opposed to the country that so many hoped that it could be. His victory was a worst-case scenario—that a convicted felon, a chronic liar who mismanaged a deadly once-in-a-century pandemic, who tried to overturn the last election and unleashed a violent mob on the nation’s Capitol, who calls America “a garbage can for the world,” and who threatens retribution against his political enemies could win—and yet, in the early morning hours of Wednesday, it happened. P

P We’re living at an exceptional moment in history. And this year’s US election is the most consequential I have witnessed since I became aware of American elections in 1980. Reagan’s two victories were critical to reviving American unity of purpose, breathing life into the economy and accelerating the demise of the Soviet Union.

We’re living at an exceptional moment in history. And this year’s US election is the most consequential I have witnessed since I became aware of American elections in 1980. Reagan’s two victories were critical to reviving American unity of purpose, breathing life into the economy and accelerating the demise of the Soviet Union. Adam Przeworski, a political scientist, left his native Poland a few months before the 1968 Prague Spring uprising and found he could not return home. To avoid being arrested as a dissident by the Communist government, he accepted a job abroad at a university in Santiago, Chile — only to watch his adopted country collapse into autocracy a few years later. In 1973, a violent coup installed a military dictatorship, led by Gen. Augusto Pinochet, wiping out Chilean democracy in one brutal stroke. “Nobody expected that it would be as bloody as it was,” Przeworski told me. “Or that it would last for 17 years.”

Adam Przeworski, a political scientist, left his native Poland a few months before the 1968 Prague Spring uprising and found he could not return home. To avoid being arrested as a dissident by the Communist government, he accepted a job abroad at a university in Santiago, Chile — only to watch his adopted country collapse into autocracy a few years later. In 1973, a violent coup installed a military dictatorship, led by Gen. Augusto Pinochet, wiping out Chilean democracy in one brutal stroke. “Nobody expected that it would be as bloody as it was,” Przeworski told me. “Or that it would last for 17 years.” Tomorrow – if we are so lucky – there will be a result. The great function that has consumed us for so long will return 0 or 1. The pundits who guessed 51-49 will be hailed as prophets; the pundits who guessed 49-51 will get bullied out of public life. The winner’s campaign operatives will be praised as world-historic geniuses, the loser’s mocked forever as utter nincompoops. Thousands of lifelong public servants who backed Mr. 49% will be tossed from DC like used toilet paper and replaced with thousands of hacks who backed Mr. 51%. Funding streams will go dry. Whole lands will turn to economic deserts. Fortunes will be destroyed. A few people will make good on their exile and suicide threats. Most won’t. The Union will either survive or not. If it survives, we’ll do it all over again four years later.

Tomorrow – if we are so lucky – there will be a result. The great function that has consumed us for so long will return 0 or 1. The pundits who guessed 51-49 will be hailed as prophets; the pundits who guessed 49-51 will get bullied out of public life. The winner’s campaign operatives will be praised as world-historic geniuses, the loser’s mocked forever as utter nincompoops. Thousands of lifelong public servants who backed Mr. 49% will be tossed from DC like used toilet paper and replaced with thousands of hacks who backed Mr. 51%. Funding streams will go dry. Whole lands will turn to economic deserts. Fortunes will be destroyed. A few people will make good on their exile and suicide threats. Most won’t. The Union will either survive or not. If it survives, we’ll do it all over again four years later. Drama serial Kabhi Main Kabhi Tum has driven its audience to a riotous appreciation that reaches far beyond the nation’s borders. Amassing millions of views on each episode uploaded on YouTube, the series takes us through the unsteady domestic lives of Sharjeena and Mustafa, who navigate the difficulties of love and honour in tandem after an eleventh-hour marital compromise. The narrative explores the bearing of financial and familial burdens on unprepared married couples, as well as the consequences of denouncing tradition to rescue dignity. Fans have praised the drama for its poised portrayal of an ordinary love story. Here’s a thorough breakdown of why the series has acquired international love.

Drama serial Kabhi Main Kabhi Tum has driven its audience to a riotous appreciation that reaches far beyond the nation’s borders. Amassing millions of views on each episode uploaded on YouTube, the series takes us through the unsteady domestic lives of Sharjeena and Mustafa, who navigate the difficulties of love and honour in tandem after an eleventh-hour marital compromise. The narrative explores the bearing of financial and familial burdens on unprepared married couples, as well as the consequences of denouncing tradition to rescue dignity. Fans have praised the drama for its poised portrayal of an ordinary love story. Here’s a thorough breakdown of why the series has acquired international love. Welcome to the healthier, happier world of 2030. Heart attacks and strokes are down 20%. A drop in food consumption has left more money in people’s wallets. Lighter passengers are saving airlines 100 million litres of fuel each year. And billions of people are enjoying a better quality of life, with improvements to their mental and physical health.

Welcome to the healthier, happier world of 2030. Heart attacks and strokes are down 20%. A drop in food consumption has left more money in people’s wallets. Lighter passengers are saving airlines 100 million litres of fuel each year. And billions of people are enjoying a better quality of life, with improvements to their mental and physical health. Fifty years ago in West Germany, a country at the heart of the growing European Communities, several innovations jumped off the production line. One was a government led by a new, outward-looking chancellor, Helmut Schmidt, who helped set up the first World Economic Summit in 1975. Another was the Volkswagen Golf, a car with an in-built radio and cassette player, perfect for cross-continental drives.

Fifty years ago in West Germany, a country at the heart of the growing European Communities, several innovations jumped off the production line. One was a government led by a new, outward-looking chancellor, Helmut Schmidt, who helped set up the first World Economic Summit in 1975. Another was the Volkswagen Golf, a car with an in-built radio and cassette player, perfect for cross-continental drives. I always try to assess facts as objectively as I can, and I always present my view of the world openly and honestly. But this is not a neutral or nonpartisan blog. I strongly endorse Kamala Harris for President, and I think the Democrats — despite some flaws — are a better choice than the Republicans at this moment in history.

I always try to assess facts as objectively as I can, and I always present my view of the world openly and honestly. But this is not a neutral or nonpartisan blog. I strongly endorse Kamala Harris for President, and I think the Democrats — despite some flaws — are a better choice than the Republicans at this moment in history. I mostly stand by the reasoning in my 2016 post,

I mostly stand by the reasoning in my 2016 post,  Several surveys suggest that many Americans still believe crime is

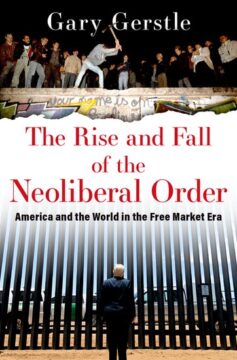

Several surveys suggest that many Americans still believe crime is  In his book “

In his book “ You can’t judge a book by its cover, but sometimes you can judge a writer’s standing by it. My 1990s-era paperback edition of “The Portable Dorothy Parker” shows the poet, critic, playwright and resident wit of the Algonquin Round Table looking stricken. Her eyes are sunken and shadowy; her hair is barely tamed; her eyes are glazed. At the time, that’s how we liked her — American literature’s cautionary tale. A notice encourages the reader to go see “Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle,” a bitter ensemble film from 1994 starring Jennifer Jason Leigh playing Parker as she begins to lose faith in writing, men and herself. Look at that book cover, and it’s clear the loss of faith is complete.

You can’t judge a book by its cover, but sometimes you can judge a writer’s standing by it. My 1990s-era paperback edition of “The Portable Dorothy Parker” shows the poet, critic, playwright and resident wit of the Algonquin Round Table looking stricken. Her eyes are sunken and shadowy; her hair is barely tamed; her eyes are glazed. At the time, that’s how we liked her — American literature’s cautionary tale. A notice encourages the reader to go see “Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle,” a bitter ensemble film from 1994 starring Jennifer Jason Leigh playing Parker as she begins to lose faith in writing, men and herself. Look at that book cover, and it’s clear the loss of faith is complete. I see at least two reasons to doubt that we are ready to abandon past transcendent realities. First, our modern ideas about morality don’t make sense without them. When secular neo-Enlightenment humanists, neo-Kantians, and effective altruists champion equality and universal human rights, they are trying to pluck an ethic from its metaphysical roots. They are essentially preaching from the theistic pulpit after tearing down the crucifix. (And we saw how that worked out for effective altruist Sam Bankman-Fried.) This hamstrung morality might limp along if the broader culture is still breathing the air of Christian values, even unconsciously, but the deeper we get inside the immanent frame, the more opportunity we give an anti-humanist Nietzsche to come along and say that our ethics are incompatible with our materialist anthropology. And what if this Nietzsche turns out to be an AI system that concludes that the best way to fix climate change is to wipe out humanity? Our moral demands may well be writing checks that our moral sources can’t cash.

I see at least two reasons to doubt that we are ready to abandon past transcendent realities. First, our modern ideas about morality don’t make sense without them. When secular neo-Enlightenment humanists, neo-Kantians, and effective altruists champion equality and universal human rights, they are trying to pluck an ethic from its metaphysical roots. They are essentially preaching from the theistic pulpit after tearing down the crucifix. (And we saw how that worked out for effective altruist Sam Bankman-Fried.) This hamstrung morality might limp along if the broader culture is still breathing the air of Christian values, even unconsciously, but the deeper we get inside the immanent frame, the more opportunity we give an anti-humanist Nietzsche to come along and say that our ethics are incompatible with our materialist anthropology. And what if this Nietzsche turns out to be an AI system that concludes that the best way to fix climate change is to wipe out humanity? Our moral demands may well be writing checks that our moral sources can’t cash.