Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

Regular Noahpinion readers will know that I’m not very excited about a second Trump term. I don’t think the next four years are going to be hell on Earth or that they’ll lead to the collapse of the nation, but I do think Trump is probably going to degrade our institutions, foment chaos, appease our enemies overseas, and appoint a lot of very unqualified people.

Regular Noahpinion readers will know that I’m not very excited about a second Trump term. I don’t think the next four years are going to be hell on Earth or that they’ll lead to the collapse of the nation, but I do think Trump is probably going to degrade our institutions, foment chaos, appease our enemies overseas, and appoint a lot of very unqualified people.

BUT, I also do have to admit that Trump’s first term turned out much better than I expected! Trump did foment social and political chaos, but consider the following:

- The economy demonstrated strong growth, with workers at the bottom of the distribution reaping especially large wage gains.

- Thanks to Trump’s rhetoric, the U.S. belatedly woke up to the various threats posed by China, and realized that unilateral free trade has many drawbacks.

- Trump did not lock Hillary Clinton up, or persecute his political enemies in general.

- Trump did great on Covid relief spending, carrying American households through the pandemic and propelling a rapid economic recovery after the pandemic.

- Trump’s Operation Warp Speed was the best Covid vaccine development effort in the world, creating new and highly effective vaccines in a very short period of time, and saving a very large number of lives.

- Very few U.S. government institutions suffered long-lasting damage as a result of Trump.

That’s not the best-case scenario for how Trump’s first term could have turned out, but it’s very far from the worst. All in all, if you told me in November 2016 that this is how Trump’s term would go, I would have breathed a sigh of relief (well, except for learning that we were going to have a giant pandemic, but that was hardly Trump’s fault).

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I ONCE ASKED Breyten Breytenbach, the exiled South African poet and painter, why, in his opinion, after the fiasco of his clandestine return to his homeland in 1975 (traveling incognito as a would-be revolutionary organizer), the calamity of his arrest (his cover having likely been blown before he even entered the country, such that not only was he arrested but virtually everyone he’d contacted was arrested as well), the debacle of his trial (his appalling, groveling breakdown, his operatic recantations and expressions of contrition, all to no avail), after his being sentenced to nine years’ hard time in the country’s notorious penal system, why, I asked him, why had the authorities who allowed him to go on writing in prison nevertheless forbidden him to paint?

I ONCE ASKED Breyten Breytenbach, the exiled South African poet and painter, why, in his opinion, after the fiasco of his clandestine return to his homeland in 1975 (traveling incognito as a would-be revolutionary organizer), the calamity of his arrest (his cover having likely been blown before he even entered the country, such that not only was he arrested but virtually everyone he’d contacted was arrested as well), the debacle of his trial (his appalling, groveling breakdown, his operatic recantations and expressions of contrition, all to no avail), after his being sentenced to nine years’ hard time in the country’s notorious penal system, why, I asked him, why had the authorities who allowed him to go on writing in prison nevertheless forbidden him to paint? Dreams can transport us anywhere—from soaring above treetops to reliving the grind of office life—but what do they truly reveal? A recent survey by Talker Research for Newsweek asked 1,000 U.S. adults about their most

Dreams can transport us anywhere—from soaring above treetops to reliving the grind of office life—but what do they truly reveal? A recent survey by Talker Research for Newsweek asked 1,000 U.S. adults about their most  Students, colleagues, and friends all saw how seriously Edward Said took clothes. “Our usual ritual upon meeting after some time apart,” a friend remembers, “was for him to look me up and down and pass withering judgments on the condition of my shoes, and to berate my obstinate reluctance to engage a proper tailor.” Said insisted another friend, a colleague at Columbia University, buy a jacket he “didn’t need (and couldn’t afford) . . .. but I couldn’t withstand the force of Edward’s solicitude, and finally went and bought one. Black. Cashmere. Very nice. I wore it for ages.” In all these accounts, Said’s clothes set him apart. “[O]ne of the features that distinguished him from the rest of us,” a fellow seminar participant recalls, “was his immaculate dress sense: everything was meticulously chosen, down to the socks. It is almost impossible to visualize him any other way.”

Students, colleagues, and friends all saw how seriously Edward Said took clothes. “Our usual ritual upon meeting after some time apart,” a friend remembers, “was for him to look me up and down and pass withering judgments on the condition of my shoes, and to berate my obstinate reluctance to engage a proper tailor.” Said insisted another friend, a colleague at Columbia University, buy a jacket he “didn’t need (and couldn’t afford) . . .. but I couldn’t withstand the force of Edward’s solicitude, and finally went and bought one. Black. Cashmere. Very nice. I wore it for ages.” In all these accounts, Said’s clothes set him apart. “[O]ne of the features that distinguished him from the rest of us,” a fellow seminar participant recalls, “was his immaculate dress sense: everything was meticulously chosen, down to the socks. It is almost impossible to visualize him any other way.” Not too long ago, Brad Pitt and Eric Bana starred in a (loose)

Not too long ago, Brad Pitt and Eric Bana starred in a (loose)  If you follow any path of ancestry back far enough, you’ll reach the same single point. Whether you begin with gorillas or ginkgo trees or bacteria that live deep in the bowels of the Earth — or yourself, for that matter — all roads lead to LUCA, the “last universal common ancestor.” This ancient, single-celled organism (or, possibly, population of single-celled organisms) was the progenitor of every varied form that makes a life for itself on our planet today.

If you follow any path of ancestry back far enough, you’ll reach the same single point. Whether you begin with gorillas or ginkgo trees or bacteria that live deep in the bowels of the Earth — or yourself, for that matter — all roads lead to LUCA, the “last universal common ancestor.” This ancient, single-celled organism (or, possibly, population of single-celled organisms) was the progenitor of every varied form that makes a life for itself on our planet today. Who could have seen Donald Trump’s resounding victory coming? Ask the question of an American intellectual these days and you may meet with embittered silence. Ask a European intellectual and you will likely hear the name of Wolfgang Streeck, a German sociologist and theorist of capitalism.

Who could have seen Donald Trump’s resounding victory coming? Ask the question of an American intellectual these days and you may meet with embittered silence. Ask a European intellectual and you will likely hear the name of Wolfgang Streeck, a German sociologist and theorist of capitalism. I

I “My friend is a late-in-life medical student with a graduate degree in art history. His hobbies include feeling sad on rainy nights, wearing expensive pajamas and reading the same John Cheever stories over and over again. He knows every smoking-allowed dive bar in Philadelphia. He sculls before class, plays tennis on the city courts and has an encyclopedic knowledge of Bill Evans recordings. His favorite things are small, impractical and impossible to find: a paperback edition of Lydia Davis’s “The Cows,” a pair of hand-painted Qajar dynasty equestrian tiles and a trompe l’oeil pen holder in the shape of a daikon radish.” — Michael, Philadelphia; budget: $75 to $100

“My friend is a late-in-life medical student with a graduate degree in art history. His hobbies include feeling sad on rainy nights, wearing expensive pajamas and reading the same John Cheever stories over and over again. He knows every smoking-allowed dive bar in Philadelphia. He sculls before class, plays tennis on the city courts and has an encyclopedic knowledge of Bill Evans recordings. His favorite things are small, impractical and impossible to find: a paperback edition of Lydia Davis’s “The Cows,” a pair of hand-painted Qajar dynasty equestrian tiles and a trompe l’oeil pen holder in the shape of a daikon radish.” — Michael, Philadelphia; budget: $75 to $100 Dmitri Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, one of the mainstays of the twentieth-century orchestral repertory, ends with an unapologetic display of musical bombast. The coda consists of thirty-five triple-forte bars in the key of D major, anchored on grandiloquent, fanfare-like gestures in the brass. The strings saw away at the note A, playing it no fewer than two hundred and fifty-two times, the winds piping along with them. The timpani pound relentlessly on D and A, the final notes accentuated by elephantine bass-drum thwacks. It is the pum-pum-pum-pum of “Also Sprach Zarathustra” run amok. The audience invariably springs to its feet.

Dmitri Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, one of the mainstays of the twentieth-century orchestral repertory, ends with an unapologetic display of musical bombast. The coda consists of thirty-five triple-forte bars in the key of D major, anchored on grandiloquent, fanfare-like gestures in the brass. The strings saw away at the note A, playing it no fewer than two hundred and fifty-two times, the winds piping along with them. The timpani pound relentlessly on D and A, the final notes accentuated by elephantine bass-drum thwacks. It is the pum-pum-pum-pum of “Also Sprach Zarathustra” run amok. The audience invariably springs to its feet. Throughout his career as a historian of science, Shapin has shown that scientific authority rests not simply on established fact but also on what people consider truth—and truth has a fundamentally social character. He has done this in books such as Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life (co-written with Simon Schaffer, 1985), A Social History of Truth: Civility and Science in Seventeenth-Century England (1994), The Scientific Life: A Moral History of a Late Modern Vocation (2008), and the admirably subtitled collection Never Pure: Historical Studies of Science as If It Was Produced by People with Bodies, Situated in Time, Space, Culture, and Society, and Struggling for Credibility and Authority (2010). These works have made him a leading scholar of the Scientific Revolution, which supplies many of his case studies (see Shapin’s The Scientific Revolution, 1996). How do scientists (or “natural philosophers”) earn each other’s trust and the public’s trust? How do they establish what counts as scientific truth, and why do we believe them? These questions go far beyond the institutional settings of the sciences. They extend, Shapin argues in Eating and Being, into our kitchens and dining rooms.

Throughout his career as a historian of science, Shapin has shown that scientific authority rests not simply on established fact but also on what people consider truth—and truth has a fundamentally social character. He has done this in books such as Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life (co-written with Simon Schaffer, 1985), A Social History of Truth: Civility and Science in Seventeenth-Century England (1994), The Scientific Life: A Moral History of a Late Modern Vocation (2008), and the admirably subtitled collection Never Pure: Historical Studies of Science as If It Was Produced by People with Bodies, Situated in Time, Space, Culture, and Society, and Struggling for Credibility and Authority (2010). These works have made him a leading scholar of the Scientific Revolution, which supplies many of his case studies (see Shapin’s The Scientific Revolution, 1996). How do scientists (or “natural philosophers”) earn each other’s trust and the public’s trust? How do they establish what counts as scientific truth, and why do we believe them? These questions go far beyond the institutional settings of the sciences. They extend, Shapin argues in Eating and Being, into our kitchens and dining rooms. For decades, Big Food has been marketing products to people who can’t stop eating, and now, suddenly, they can. The active ingredient in Ozempic, as in Wegovy, Zepbound and several other similar new drugs, mimics a natural hormone, called glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), that slows digestion and signals fullness to the brain. Around seven million Americans now take a GLP-1 drug, and Morgan Stanley estimates that by

For decades, Big Food has been marketing products to people who can’t stop eating, and now, suddenly, they can. The active ingredient in Ozempic, as in Wegovy, Zepbound and several other similar new drugs, mimics a natural hormone, called glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), that slows digestion and signals fullness to the brain. Around seven million Americans now take a GLP-1 drug, and Morgan Stanley estimates that by  The Secretary of Health and Human Services oversees an enormous federal agency in charge of Medicare, Medicaid, federally funded biomedical research, public health, and drug approval. In other words, it’s a very important job—and the health of the American people is in that person’s hands.

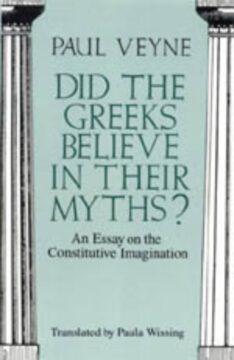

The Secretary of Health and Human Services oversees an enormous federal agency in charge of Medicare, Medicaid, federally funded biomedical research, public health, and drug approval. In other words, it’s a very important job—and the health of the American people is in that person’s hands. By 1140, when the Italian monk Gratian compiled the first collection of ecclesiastical laws, the Corpus Juris Canonici, the last Olympic Games were 747 years in the past, held in the same year that the Oracle of Delphi delivered its last prophecy, a little more than a century before the Byzantine emperor Justinian I closed Plato’s Academy, in 529 CE. Ever since Rome became Christian, starting with its legalization by Constantine I in 313 and then its establishment as the religion of the empire by Theodosius 380, Europe had existed in the long dusk of its classical past, the ancient rites discarded or suppressed, the oracles made mute, the gods gone silent. Yet within Gratian’s compendium, with its stipulations for restitution and penitence, there is a curious section that mandates a “penance for forty days on bread and water” for those who have “observed Thursday in honor of Jupiter.” In another section, there is discussion of the punishment warranted for those caught worshipping Diana, the Roman goddess of the hunt. If these penitentials reflect a reality in the twelfth century, are we then to imagine that in the age of Peter Abelard and Hildegard von Bingen and of the Cathedrals at Notre Dame and Westminster Abbey, that there were people still genuflecting before Jupiter?

By 1140, when the Italian monk Gratian compiled the first collection of ecclesiastical laws, the Corpus Juris Canonici, the last Olympic Games were 747 years in the past, held in the same year that the Oracle of Delphi delivered its last prophecy, a little more than a century before the Byzantine emperor Justinian I closed Plato’s Academy, in 529 CE. Ever since Rome became Christian, starting with its legalization by Constantine I in 313 and then its establishment as the religion of the empire by Theodosius 380, Europe had existed in the long dusk of its classical past, the ancient rites discarded or suppressed, the oracles made mute, the gods gone silent. Yet within Gratian’s compendium, with its stipulations for restitution and penitence, there is a curious section that mandates a “penance for forty days on bread and water” for those who have “observed Thursday in honor of Jupiter.” In another section, there is discussion of the punishment warranted for those caught worshipping Diana, the Roman goddess of the hunt. If these penitentials reflect a reality in the twelfth century, are we then to imagine that in the age of Peter Abelard and Hildegard von Bingen and of the Cathedrals at Notre Dame and Westminster Abbey, that there were people still genuflecting before Jupiter?