From Harper’s Magazine:

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

There in the park where I played as a kid

I saw them painting the brown grass green.

Just us early risers and the unfolding of the nascent day—

the clustered clarity of it all impinging trenchantly

on my slowly developing take of things

so early in the morning—

Entering into commerce I saw those who were unable

doing the best they could—

compromised by issues which they’ll never overcome

but loved nonetheless by someone somewhere—

and there was a twang in the rusty heartstrings.

Later in the darkness I saw something altogether

different—it looked like a searing flame but it was just

the flickering glow of a huge TV—the actualities

dawning, yawning; colored as they were with their

unsettling palette of tempered uncertainty.

Recollecting the future while anticipating the past

I set out to reconcile the paradoxes

only to arrive somewhere else entirely

and undergo the heavyweight realization that the

paradoxes have long since—maybe even always—

been wholly reconciled.

by Mark Terrill

from Empty Mirror

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sahana Sitaraman in The Scientist:

Glucose is the fuel to the cellular engine. It powers the cell’s functions and serves as the raw material for synthesizing various essential biomolecules, including the sugar backbone of DNA and RNA. It is crucial for the growth and proliferation of all cells in the body, including cancer cells. Yet, cancer cells thrive despite the fact that their surrounding environment—the tumor microenvironment—is severely depleted of glucose.1 In a new study published today (November 26) in Nature Metabolism, researchers at New York University Grossman School of Medicine reported that in the presence of certain chemotherapy drugs, cancer cells rewire their metabolisms to use a glucose-depleted tumor microenvironment to their advantage and escape death.2 “Our study shows how cancer cells manage to offset the impact of low-glucose tumor microenvironments, and how these changes in cancer cell metabolism minimize chemotherapy’s effectiveness,” said Richard Possemato, a cancer biologist and coauthor of the paper, in a press release.

Glucose is the fuel to the cellular engine. It powers the cell’s functions and serves as the raw material for synthesizing various essential biomolecules, including the sugar backbone of DNA and RNA. It is crucial for the growth and proliferation of all cells in the body, including cancer cells. Yet, cancer cells thrive despite the fact that their surrounding environment—the tumor microenvironment—is severely depleted of glucose.1 In a new study published today (November 26) in Nature Metabolism, researchers at New York University Grossman School of Medicine reported that in the presence of certain chemotherapy drugs, cancer cells rewire their metabolisms to use a glucose-depleted tumor microenvironment to their advantage and escape death.2 “Our study shows how cancer cells manage to offset the impact of low-glucose tumor microenvironments, and how these changes in cancer cell metabolism minimize chemotherapy’s effectiveness,” said Richard Possemato, a cancer biologist and coauthor of the paper, in a press release.

The improved understanding of the tumor microenvironment’s impact on the growth and survival of cancer cells will help guide the development of targeted treatments and predict responses to drugs under specific conditions.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Edith Hall at Aeon Magazine:

I’m an Aristotle scholar but also an enthusiast for his ideas. I’ve studied his work in the original Greek, and even made a pilgrimage to his birthplace and the various places he lived. He was the most brilliant philosopher ever to have lived. I believe that his Nicomachean Ethics offers us a guide for how to live good lives and flourish. Oddly, though, for a writer whose thinking was so clear and, in many ways, modern, people with radically different stances have tried to claim him for their own.

I’m an Aristotle scholar but also an enthusiast for his ideas. I’ve studied his work in the original Greek, and even made a pilgrimage to his birthplace and the various places he lived. He was the most brilliant philosopher ever to have lived. I believe that his Nicomachean Ethics offers us a guide for how to live good lives and flourish. Oddly, though, for a writer whose thinking was so clear and, in many ways, modern, people with radically different stances have tried to claim him for their own.

He often features as a darling of Right-wing ideologues: his Politics is the first text in Benjamin Wiker’s 10 Books Every Conservative Must Read (2010); his authority is invoked on the Breitbart News website. Yet he is celebrated by Marxists for identifying the importance of economic factors in political history, having been heroised in Hugo Gellert’s Karl Marx’ ‘Capital’ in Lithographs (1934). Over the past decade, Aristotle’s face has appeared in Greek wall-art protesting against austerity along with his statement that poverty engenders revolution and crime. On the other hand, his (misinterpreted) views on elites, women and slavery in his Politics are often censured, especially since the advent of ‘cancel’ culture. Yet he has a significant record and potential as a radical and reforming force. This has been overlooked because his views on constitutional issues, the equality of women and even slavery have often been misrepresented, distorted and downright falsified.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

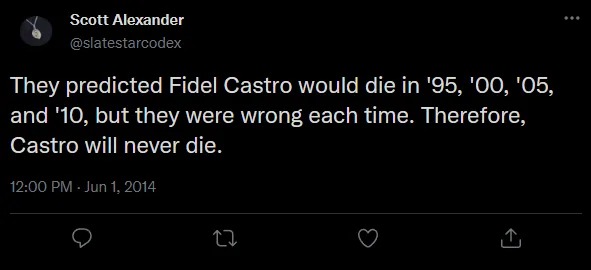

Scott Alexander at Astral Codex Ten:

Suppose something important will happen at a certain unknown point. As someone approaches that point, you might be tempted to warn that the thing will happen. If you’re being appropriately cautious, you’ll warn about it before it happens. Then your warning will be wrong. As things continue to progress, you may continue your warnings, and you’ll be wrong each time. Then people will laugh at you and dismiss your predictions, since you were always wrong before. Then the thing will happen and they’ll be unprepared.

Suppose something important will happen at a certain unknown point. As someone approaches that point, you might be tempted to warn that the thing will happen. If you’re being appropriately cautious, you’ll warn about it before it happens. Then your warning will be wrong. As things continue to progress, you may continue your warnings, and you’ll be wrong each time. Then people will laugh at you and dismiss your predictions, since you were always wrong before. Then the thing will happen and they’ll be unprepared.

Toy example: suppose you’re a doctor. Your patient wants to try a new experimental drug, 100 mg. You say “Don’t do it, we don’t know if it’s safe”. They do it anyway and it’s fine. You say “I guess 100 mg was safe, but don’t go above that.” They try 250 mg and it’s fine. You say “I guess 250 mg was safe, but don’t go above that.” They try 500 mg and it’s fine. You say “I guess 500 mg was safe, but don’t go above that.”

They say “Haha, as if I would listen to you! First you said it might not be safe at all, but you were wrong. Then you said it might not be safe at 250 mg, but you were wrong. Then you said it might not be safe at 500 mg, but you were wrong. At this point I know you’re a fraud! Stop lecturing me!” Then they try 1000 mg and they die.

The lesson is: “maybe this thing that will happen eventually will happen now” doesn’t count as a failed prediction.

I’ve noticed this in a few places recently.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Quico Toro at Persuasion:

Are hurricanes getting more intense due to climate change? This is one of those questions that seems straightforward—almost banal—but gets weirder the closer you look into it. The discussion atmospheric scientists are having about the drivers of the trend towards stronger hurricanes has shockingly little in common with the simplified story you get in the press.

Are hurricanes getting more intense due to climate change? This is one of those questions that seems straightforward—almost banal—but gets weirder the closer you look into it. The discussion atmospheric scientists are having about the drivers of the trend towards stronger hurricanes has shockingly little in common with the simplified story you get in the press.

The standard media narrative begins by comparing hurricane trends so far this century with the three preceding decades. They stress that sea surface temperatures have risen substantially since the late 20th century, and warm oceans are hurricane fuel: the hotter the ocean, the stronger the storm.

“Warm Air and Warm Oceans Power Storms Like Debby,” ran a New York Times headline this summer. Last week, Axios reported that “Due to warming ocean waters and air temperatures from human emissions of greenhouse gasses, tropical storms and hurricanes are now delivering heavier precipitation than just a few decades ago.”

The message is that there’s a nice, neat, clean relationship: more greenhouse gas emissions means a hotter planet, which means warmer oceans, which means stronger hurricanes.

The end.

But this story isn’t quite right.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Patrick Fealey in Esquire:

3:00 a.m., parked in a public lot across the street from the town beach in Westerly, Rhode Island. Just woke up, sleep evasive. It’s my first week out here. I pour an iced coffee from my cooler. I’m walking around the front of the Toyota I’m now living in when a car pulls into the lot, comes toward me. I see only headlights illuminating my fatigue and the red plastic party cup in my hand. Must be a cop. Someone gets out and approaches. It is a cop, young. I’m not afraid, exactly, but I’m also not yet used to being homeless.

3:00 a.m., parked in a public lot across the street from the town beach in Westerly, Rhode Island. Just woke up, sleep evasive. It’s my first week out here. I pour an iced coffee from my cooler. I’m walking around the front of the Toyota I’m now living in when a car pulls into the lot, comes toward me. I see only headlights illuminating my fatigue and the red plastic party cup in my hand. Must be a cop. Someone gets out and approaches. It is a cop, young. I’m not afraid, exactly, but I’m also not yet used to being homeless.

“How you doing?” he says.

“Good.”

“Just hanging out?”

“Yes.”

“Are you okay?”

“Yes.”

“Do you need anything?”

“No.”

“Okay. Just checking. Have a good night.”

In the morning, I awake with back pain. Sleeping in the driver’s seat will be an acquired skill.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Green midnight at the nightingale’s northernmost border. The heavy leaves

hang entranced deafening the automobiles’ rush towards some neon line.

The path of the nightingale’s voice is not beside the point. It is like a break-through,

like a rooster’s madness, but beautiful and without vanity. I was in prison

and it visited me. I was sick and it attended me. Then I did not heed it,

but I do now. Time’s stream flows down from the sun and moon through

the tick-tock, tick-tockings of all clocks. But just here, no time exists – only

the nightingale’s voice. It has the power to ring notes as polished as

the night sky’s scythe of light.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Ruvani Ranasinha in The Guardian:

Two years ago, on Boxing Day 2022, novelist and screenwriter Hanif Kureishi suffered a fall in Rome that left him paralysed. Since then, with the help of family members, he has been recounting his devastating experience of “becoming divorced from [himself]” on Substack and in a memoir, Shattered, published earlier this year.

Two years ago, on Boxing Day 2022, novelist and screenwriter Hanif Kureishi suffered a fall in Rome that left him paralysed. Since then, with the help of family members, he has been recounting his devastating experience of “becoming divorced from [himself]” on Substack and in a memoir, Shattered, published earlier this year.

The author, who turns 70 next month, has had to adjust just about everything in his life. But that hasn’t stemmed his creative output: as well as the memoir, this year Kureishi adapted his acclaimed novel The Buddha of Surburbia for stage with the theatre director Emma Rice, which has just finished a second run at the Barbican in London. For those wanting to dive deeper into the author’s work, there’s plenty to explore: from his early essays and screenplays to his novels, memoirs and short stories, Kureishi’s biographer Ruvani Ranasinha suggests some good ways in.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

As a medical doctor, my mother isn’t afraid of needles. But when she recently began injecting insulin daily for her newly diagnosed diabetes, the shots became a frustrating nuisance. A jab is a standard way to deliver insulin, antibodies, RNA vaccines, GLP-1 drugs such as Ozempic, and other large molecules. Compared to small chemicals—say, aspirin—these drugs often contain molecules that are easily destroyed if taken as pills, making injection the best option.

As a medical doctor, my mother isn’t afraid of needles. But when she recently began injecting insulin daily for her newly diagnosed diabetes, the shots became a frustrating nuisance. A jab is a standard way to deliver insulin, antibodies, RNA vaccines, GLP-1 drugs such as Ozempic, and other large molecules. Compared to small chemicals—say, aspirin—these drugs often contain molecules that are easily destroyed if taken as pills, making injection the best option.

But no one likes needles. Discomfort aside, they can also cause infection, skin irritation, and other side effects. Scientists have long tried to avoid injections with other drug delivery options—most commonly, pills—if they can overcome the downsides. This month, researchers from MIT and the pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk took inspiration from squids to engineer ingestible capsules that burst inside the stomach and other parts of the digestive system. The pills mimic a squid-like jet to “spray” their cargo into tissue. They make use of two spraying mechanisms. One works best in larger organs, such as the stomach and colon. Another delivers treatments in narrower organs, like the esophagus.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Jonathan Clark in Esquire:

On March 20, 1995, members of a religious cult released toxic gas in three Tokyo subways, killing thirteen people. Some months later, the Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami happened to be reading the letters page of a banal Ladies’ Home Journal–type magazine in which a reader described her husband’s psychological inability to return to his job at the transit authority after surviving the terrorist attack. Murakami decided to interview survivors to examine the many traumatic effects of such a horrific event. The resulting book, Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche, is an oral history in the vein of Studs Terkel. In one of the few moments that come from Murakami and not the victims, he inadvertently summarizes one of the core themes of his fiction. Without the ego, he explains, we lose the “narrative” of our identities, which, for him, is vital for our ability to connect with others.

On March 20, 1995, members of a religious cult released toxic gas in three Tokyo subways, killing thirteen people. Some months later, the Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami happened to be reading the letters page of a banal Ladies’ Home Journal–type magazine in which a reader described her husband’s psychological inability to return to his job at the transit authority after surviving the terrorist attack. Murakami decided to interview survivors to examine the many traumatic effects of such a horrific event. The resulting book, Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche, is an oral history in the vein of Studs Terkel. In one of the few moments that come from Murakami and not the victims, he inadvertently summarizes one of the core themes of his fiction. Without the ego, he explains, we lose the “narrative” of our identities, which, for him, is vital for our ability to connect with others.

Of course, a narrative is a “story,” and “stories” are neither logic, nor ethics. It is a dream you continue to have. You might, in fact, not even be aware of it. But, just like breathing, you continue incessantly to see this dream. In this dream you are just an existence with two faces. You are at once corporeal and shadow. You are the “maker” of the narrator, and at the same time you are the “player” who experiences the narrative.

Translated by Matthew Carl Strecher

The inescapable duality of human consciousness—that is the terrain of much of Murakami’s fiction. What drew him to this work of reportage also animates his inventions. Murakami’s approach to consciousness is less representational than literal, with many of his characters literally being transported to a realm created by (or wholly inside of) their minds.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Susan Dominus in The New York Times:

In the days after Daphna Cardinale delivered her second child, she experienced a rare sense of calm and wonder. The feeling was a relief after so much worrying: She and her husband, Alexander, had tried for three years to conceive before turning to in vitro fertilization, and Daphna, once pregnant, had frequent and painful early contractions. But now, miraculously, here was their baby, their perfect baby, May, with black hair plastered on her head. (May is a nickname that her parents requested to protect her privacy.)

In the days after Daphna Cardinale delivered her second child, she experienced a rare sense of calm and wonder. The feeling was a relief after so much worrying: She and her husband, Alexander, had tried for three years to conceive before turning to in vitro fertilization, and Daphna, once pregnant, had frequent and painful early contractions. But now, miraculously, here was their baby, their perfect baby, May, with black hair plastered on her head. (May is a nickname that her parents requested to protect her privacy.)

Because everything about May felt like an unexpected gift, Daphna was not surprised to find that she was an easy newborn: a good eater, a strong sleeper. The couple settled May into her lavender bedroom in their home in a suburb of Los Angeles. Daphna, on leave from her work as a therapist, was grateful for the bounty of two children, overjoyed that she could deliver to her older daughter, Olivia, then 5, the sister she had begged for since she could speak in full sentences.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Dario Amodei at his own website:

I think and talk a lot about the risks of powerful AI. The company I’m the CEO of, Anthropic, does a lot of research on how to reduce these risks. Because of this, people sometimes draw the conclusion that I’m a pessimist or “doomer” who thinks AI will be mostly bad or dangerous. I don’t think that at all. In fact, one of my main reasons for focusing on risks is that they’re the only thing standing between us and what I see as a fundamentally positive future. I think that most people are underestimating just how radical the upside of AI could be, just as I think most people are underestimating how bad the risks could be.

I think and talk a lot about the risks of powerful AI. The company I’m the CEO of, Anthropic, does a lot of research on how to reduce these risks. Because of this, people sometimes draw the conclusion that I’m a pessimist or “doomer” who thinks AI will be mostly bad or dangerous. I don’t think that at all. In fact, one of my main reasons for focusing on risks is that they’re the only thing standing between us and what I see as a fundamentally positive future. I think that most people are underestimating just how radical the upside of AI could be, just as I think most people are underestimating how bad the risks could be.

In this essay I try to sketch out what that upside might look like—what a world with powerful AI might look like if everything goes right. Of course no one can know the future with any certainty or precision, and the effects of powerful AI are likely to be even more unpredictable than past technological changes, so all of this is unavoidably going to consist of guesses. But I am aiming for at least educated and useful guesses, which capture the flavor of what will happen even if most details end up being wrong. I’m including lots of details mainly because I think a concrete vision does more to advance discussion than a highly hedged and abstract one.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

James O’Donnell at the MIT Technology Review:

Imagine sitting down with an AI model for a spoken two-hour interview. A friendly voice guides you through a conversation that ranges from your childhood, your formative memories, and your career to your thoughts on immigration policy. Not long after, a virtual replica of you is able to embody your values and preferences with stunning accuracy.

Imagine sitting down with an AI model for a spoken two-hour interview. A friendly voice guides you through a conversation that ranges from your childhood, your formative memories, and your career to your thoughts on immigration policy. Not long after, a virtual replica of you is able to embody your values and preferences with stunning accuracy.

That’s now possible, according to a new paper from a team including researchers from Stanford and Google DeepMind, which has been published on arXiv and has not yet been peer-reviewed.

Led by Joon Sung Park, a Stanford PhD student in computer science, the team recruited 1,000 people who varied by age, gender, race, region, education, and political ideology. They were paid up to $100 for their participation. From interviews with them, the team created agent replicas of those individuals. As a test of how well the agents mimicked their human counterparts, participants did a series of personality tests, social surveys, and logic games, twice each, two weeks apart; then the agents completed the same exercises. The results were 85% similar.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Gianpaolo Baiocchi in the Boston Review:

Fernando Morais’s Lula, a new biography of Brazil’s current third-term president, describes the tension on the morning of April 7, 2018. The night before, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—known simply as “Lula”—had been charged with corruption and given a day to turn himself in. He’d headed to São Paulo’s Metalworkers Union headquarters to discuss his next moves with a few close associates. “As the sun came up, fourteen of the twenty-four hours given by Judge Moro had come and gone,” Morais writes. “They can come and get me here,” Lula announces.

Fernando Morais’s Lula, a new biography of Brazil’s current third-term president, describes the tension on the morning of April 7, 2018. The night before, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—known simply as “Lula”—had been charged with corruption and given a day to turn himself in. He’d headed to São Paulo’s Metalworkers Union headquarters to discuss his next moves with a few close associates. “As the sun came up, fourteen of the twenty-four hours given by Judge Moro had come and gone,” Morais writes. “They can come and get me here,” Lula announces.

By that morning, the union hall has filled with union comrades, Lula’s Workers’ Party (PT) members, clergy, and activists from Lula’s past, setting the stage for a dramatic standoff between Lula and his supporters—and by extension, ordinary Brazilians—and the powerful defenders of privilege who controlled the judiciary. Brazil’s media giant, Globo, had falsely reported that Lula intended to resist arrest, and emotions were running high. At one point, there are fears that power to the union hall would be cut, and Lula’s supporters discover hidden listening devices and cameras planted by police agents. Less than a kilometer away, riot police are ready to raid the building. Morais captures Lula’s back-and-forth with his closest allies, some of whom urge him to flee.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thomas Hochman at The New Atlantis:

Ever since Derek Thompson introduced the term “abundance agenda” in his 2022 Atlantic article “A Simple Plan to Solve All of America’s Problems,” the idea has spun out into a network of new think tanks, conferences, and newsletters — and of social circles that often begin online. At a recent abundance-themed happy hour, I found myself in a room with a hundred people whose names I recognized from Twitter. But the idea has also captured the interest of a number of elite tastemakers, from New York Times columnist Ezra Klein to Silicon Valley giant Patrick Collison. Abundance seems to have gained traction.

The abundance agenda first emerged as a response to Covid-related supply-chain failures. Many commentators remarked on the prolonged shortage of Covid tests well over a year into the pandemic: How was it that the United States still had people standing in lines for rapid tests costing $15 or more, while Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom were selling them at corner stores for less than a dollar a pop, or handing them out for free? In a country as wealthy as ours, many reasoned, this sort of scarcity must be a policy choice.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Stephen Squibb at n+1:

In his 1974 “social sculpture” I Like America and America Likes Me, the artist Jospeh Beuys spent three days locked in a gallery with a wild coyote. I often think of Beuys when I think of François Laruelle, the enormously important French thinker who died Monday morning at age 87, and who spent his entire career locked in a similarly intimate and dramatic confrontation with philosophy.

In his 1974 “social sculpture” I Like America and America Likes Me, the artist Jospeh Beuys spent three days locked in a gallery with a wild coyote. I often think of Beuys when I think of François Laruelle, the enormously important French thinker who died Monday morning at age 87, and who spent his entire career locked in a similarly intimate and dramatic confrontation with philosophy.

Why would such a confrontation be necessary? Consider Friedrich Engels’s famous quip that, in what would become The German Ideology, he and Marx intended to “settle accounts with our erstwhile philosophical conscience,” thus clearing the way for their departure from a post-Hegelian “utopian” socialism to a more “scientific” kind anchored in the critique of political economy. The possibility of this move—from something called philosophy to something more scientific—is the all-consuming theme considered by Laruelle over six decades and countless books since completing his dissertation at the École Normale Supérieure under Paul Ricœur. This is his immense project of “non-philosophy,” which, in a kind of everlasting dance of participation and description, seeks not so much to transcend or escape philosophy as to show what such an exit strategy might require.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.