Angela Haupt in Time Magazine:

Thirty years ago, when Thomas Brinthaupt became a new parent—and was in the thick of long, sleep-deprived days and nights—he started coping by talking out loud to himself. That inspired him to research why people engage in this type of self-talk. A few key reasons have emerged, including social isolation: As you might expect, people who spend lots of time alone are more likely to keep themselves company by chit-chatting out loud. (Brinthaupt’s mother lived by herself, and after he overheard her solo conversations, she told him talking to herself helped her get through the day.) The same goes for only children—who engage in self-talk more frequently than those with siblings—as well as adults who had an imaginary companion they talked to when they were kids.

Thirty years ago, when Thomas Brinthaupt became a new parent—and was in the thick of long, sleep-deprived days and nights—he started coping by talking out loud to himself. That inspired him to research why people engage in this type of self-talk. A few key reasons have emerged, including social isolation: As you might expect, people who spend lots of time alone are more likely to keep themselves company by chit-chatting out loud. (Brinthaupt’s mother lived by herself, and after he overheard her solo conversations, she told him talking to herself helped her get through the day.) The same goes for only children—who engage in self-talk more frequently than those with siblings—as well as adults who had an imaginary companion they talked to when they were kids.

The other main reason why people talk out loud to themselves is to deal with “situations that are novel or highly stressful, or where you’re not sure what to do or think or feel,” says Brinthaupt, a professor emeritus of psychology at Middle Tennessee State University. Studies have found that when you’re anxious or experiencing, for example, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, you’re much more likely to talk to yourself. Upsetting or disturbing experiences make people want to resolve or understand them—and self-talk is a tool that helps them do so, he says.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Researchers are flocking to the social-media platform Bluesky, hoping to recreate the good old days of Twitter.

Researchers are flocking to the social-media platform Bluesky, hoping to recreate the good old days of Twitter. Can a book change a landscape? If ever a book did, it was The Great Gatsby. And if The Great Gatsby did, it did so thanks to one of its first and most ambitious readers, the urban planner Robert Moses.

Can a book change a landscape? If ever a book did, it was The Great Gatsby. And if The Great Gatsby did, it did so thanks to one of its first and most ambitious readers, the urban planner Robert Moses. The generalized efficient markets (GEM) principle says, roughly, that things which would give you a big windfall of money and/or status, will not be easy. If such an opportunity were available, someone else would have already taken it. You will never find a $100 bill on the floor of Grand Central Station at rush hour, because someone would have picked it up already.

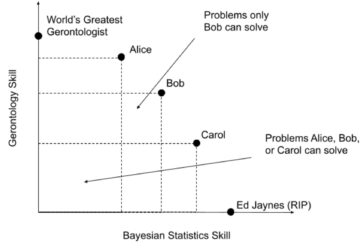

The generalized efficient markets (GEM) principle says, roughly, that things which would give you a big windfall of money and/or status, will not be easy. If such an opportunity were available, someone else would have already taken it. You will never find a $100 bill on the floor of Grand Central Station at rush hour, because someone would have picked it up already. When Scientific American was bad under Helmuth, it was really bad. For example, did you know that “

When Scientific American was bad under Helmuth, it was really bad. For example, did you know that “

No quote from antiquity sums up the metaphysical challenge of being a surfer more aptly than this one, from Marcus Aurelius, the last Emperor of the Pax Romana: “There is a river of creation, and time is a violent stream. As soon as one thing comes into sight, it is swept past and another is carried down: it too will be taken on its way.” Waves, by their nature, do not hold still. “Catching” one, therefore, can be a kind of thought experiment, a quantum paradox. To hitch yourself onto a surge of liquid energy—to soar across its frothing surface—demands both physical and mental suspension of disbelief.

No quote from antiquity sums up the metaphysical challenge of being a surfer more aptly than this one, from Marcus Aurelius, the last Emperor of the Pax Romana: “There is a river of creation, and time is a violent stream. As soon as one thing comes into sight, it is swept past and another is carried down: it too will be taken on its way.” Waves, by their nature, do not hold still. “Catching” one, therefore, can be a kind of thought experiment, a quantum paradox. To hitch yourself onto a surge of liquid energy—to soar across its frothing surface—demands both physical and mental suspension of disbelief. A

A A

A

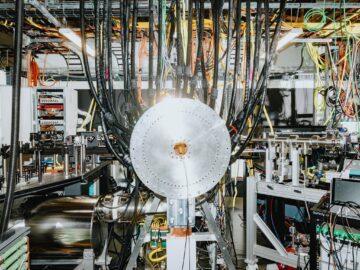

Big-name investors including Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Vinod Khosla and Sam Altman have staked hundreds of millions of dollars on this, fusion’s potential

Big-name investors including Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Vinod Khosla and Sam Altman have staked hundreds of millions of dollars on this, fusion’s potential  I

I

The Monty Python sketch of Thomas Hardy writing “The Return of the Native” takes place inside a packed soccer stadium with an announcer providing play-by-play analysis of the author’s glacial writing process. In hushed tones, the announcer says that Hardy has started to write, but wait, “oh no, it’s a doodle … a piece of meaningless scribble.” At last, Hardy writes “the,” but then crosses it out. In the time it takes to play an entire soccer match, he barely produces a sentence. In fact, Hardy was a speedy writer. He created “The Mayor of Casterbridge” so quickly that if he were outside, he “would scribble on large dead leaves or pieces of stone or slate that came to hand,” Paula Byrne writes in a new biography, “

The Monty Python sketch of Thomas Hardy writing “The Return of the Native” takes place inside a packed soccer stadium with an announcer providing play-by-play analysis of the author’s glacial writing process. In hushed tones, the announcer says that Hardy has started to write, but wait, “oh no, it’s a doodle … a piece of meaningless scribble.” At last, Hardy writes “the,” but then crosses it out. In the time it takes to play an entire soccer match, he barely produces a sentence. In fact, Hardy was a speedy writer. He created “The Mayor of Casterbridge” so quickly that if he were outside, he “would scribble on large dead leaves or pieces of stone or slate that came to hand,” Paula Byrne writes in a new biography, “