““Art is the proper task of life,”

………………………. —Nietzsche

Inner Life

Art is an essential part of life. Without its depth

and enrichment, our lives would dry like desert dew

at the break of dawn.

Art enhances human experience by offering beauty,

inspiration, and a means to navigate and interpret the

complexities of being, the magic, the mayhem,

and the throbbing mysteries surrounding us.

In the words of Jean-Luc Godard:

Art attracts us only by what it reveals

of our most secret self.

The creative act is an activity of our inner life,

the dominion of spirit over the material world

serving as a metaphysical lens enabling us

to perceive life with greater depth and nuance.

by Erik Rittenberry

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sara Belhouari, a financial advisor based in Brooklyn, is implementing what she calls “financial activism,” a process that involves spending her money with more intentionality. She’s been rethinking her support of large corporations. With companies—

Sara Belhouari, a financial advisor based in Brooklyn, is implementing what she calls “financial activism,” a process that involves spending her money with more intentionality. She’s been rethinking her support of large corporations. With companies— On Dec. 20, OpenAI announced o3, its latest model, and

On Dec. 20, OpenAI announced o3, its latest model, and  Dear Wolf,

Dear Wolf, One need only glance at headlines about

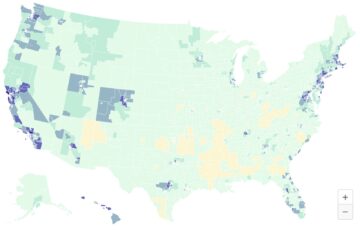

One need only glance at headlines about  US science has been transformational for the United States and for the world. Research today is a hugely collaborative enterprise. The big discoveries and innovations happen when researchers are able to communicate with, learn from, visit, and live and work with researchers in different countries. This allows for the efficient exchange of knowledge and for the best and brightest to work together no matter where they happen to have been born, giving breakthroughs the best chance of success. We urge you and your administration to ensure that the United States continues to welcome researchers from all parts of the world.

US science has been transformational for the United States and for the world. Research today is a hugely collaborative enterprise. The big discoveries and innovations happen when researchers are able to communicate with, learn from, visit, and live and work with researchers in different countries. This allows for the efficient exchange of knowledge and for the best and brightest to work together no matter where they happen to have been born, giving breakthroughs the best chance of success. We urge you and your administration to ensure that the United States continues to welcome researchers from all parts of the world. David Lynch once said he was inspired to become a filmmaker when, while painting, he inexplicably heard a gust of wind and saw the artwork move on canvas.

David Lynch once said he was inspired to become a filmmaker when, while painting, he inexplicably heard a gust of wind and saw the artwork move on canvas. Here is some of the greatest, most practical advice I’ve heard on how to start reading poetry: “A poem is best read in the light of all the other poems ever written. We read A the better to read B (we have to start somewhere; we may get very little out of A). We read B the better to read C, C the better to read D, D the better to go back and get something more out of A.”

Here is some of the greatest, most practical advice I’ve heard on how to start reading poetry: “A poem is best read in the light of all the other poems ever written. We read A the better to read B (we have to start somewhere; we may get very little out of A). We read B the better to read C, C the better to read D, D the better to go back and get something more out of A.” Asterisk: I wanted to start by asking you about your work on prison gangs in California. How did these gangs come to be?

Asterisk: I wanted to start by asking you about your work on prison gangs in California. How did these gangs come to be? The association between alcohol and cancer isn’t new news – scientists have been

The association between alcohol and cancer isn’t new news – scientists have been  Down a tree-lined street near my grandmother’s house in Tehran is a mosque where locals go to chat, rest, and sometimes even pray. In the back of the mosque, behind a small library, is an office for a youth group that organizes volunteers to teach classes, run food drives, get together on religious holidays, and take trips to impoverished villages on Tehran’s outskirts to build schools. Whenever I visit my grandmother’s house during Muharram, a holy month for Shia Muslims, I see its members handing out food and sweets. The group has branches in most mosques across Iran: within a twenty-minute walk from my grandmother’s house, there are probably half a dozen. They receive a government budget, and they host political events, like celebrations of the anniversary of the 1979 Revolution. Millions of Iranians are members; many are teenagers or young adults, separated into boys’ and girls’ groups.

Down a tree-lined street near my grandmother’s house in Tehran is a mosque where locals go to chat, rest, and sometimes even pray. In the back of the mosque, behind a small library, is an office for a youth group that organizes volunteers to teach classes, run food drives, get together on religious holidays, and take trips to impoverished villages on Tehran’s outskirts to build schools. Whenever I visit my grandmother’s house during Muharram, a holy month for Shia Muslims, I see its members handing out food and sweets. The group has branches in most mosques across Iran: within a twenty-minute walk from my grandmother’s house, there are probably half a dozen. They receive a government budget, and they host political events, like celebrations of the anniversary of the 1979 Revolution. Millions of Iranians are members; many are teenagers or young adults, separated into boys’ and girls’ groups. Benjamin and Lācis’s “Naples” gives its readers a glimpse of a unified world of cross-relationships, in which discontinuous elements are somehow all implicated in one another and intermingled. In their telling, Naples, with its “rich barbarism,” blissfully flouted the bourgeois norms of northern Europe without knowing it. Streets were treated as living rooms and living rooms were treated as streets; festivals invaded every working day; the division between night and day was never neatly observed. To Benjamin and Lācis’s delight, Neapolitans had not received the news about the evacuation of the sacred from the modern world. In one of the article’s scenes, a Catholic priest accused of indecent offenses is described being led down a street while a crowd shouts insults at him. Suddenly, when a wedding procession passes by, the priest gives the sign of a blessing, and his pursuers fall to their knees.

Benjamin and Lācis’s “Naples” gives its readers a glimpse of a unified world of cross-relationships, in which discontinuous elements are somehow all implicated in one another and intermingled. In their telling, Naples, with its “rich barbarism,” blissfully flouted the bourgeois norms of northern Europe without knowing it. Streets were treated as living rooms and living rooms were treated as streets; festivals invaded every working day; the division between night and day was never neatly observed. To Benjamin and Lācis’s delight, Neapolitans had not received the news about the evacuation of the sacred from the modern world. In one of the article’s scenes, a Catholic priest accused of indecent offenses is described being led down a street while a crowd shouts insults at him. Suddenly, when a wedding procession passes by, the priest gives the sign of a blessing, and his pursuers fall to their knees. More Americans are surviving cancer, but the disease is striking young and middle-aged adults and women more frequently, the

More Americans are surviving cancer, but the disease is striking young and middle-aged adults and women more frequently, the  Lubitsch scholars have often remarked on the simplicity of The Shop Around the Corner. This is true in a technical sense. There are no trick angles, long shots, travelings, flashbacks, elaborate sets. The story was filmed sequentially in less than a month. In an interview in the New York Sun, Lubitsch called it “a quiet little story that seemed to have some charm.” His remark alludes to the comical, error-ridden romance between two shop employees. But there is a second storyline, less discussed, whose protagonist is Matuschek (Frank Morgan), the owner of the shop. If one watches through his eyes, one sees a different movie than the romantic comedy that it’s universally taken to be. From this perspective, there is nothing funny or romantic about the film. Pauline Kael distinguished between the plays and the screenplays of Samson Raphaelson, who wrote the script, by noting that the former are not lighthearted: “They aspired to be more than comedies; there was always a serious kernel.” His screenplay for The Shop Around the Corner is an exception to Kael’s rule, for the Matuschek material contains a kernel of seriousness buried inside a comedy.

Lubitsch scholars have often remarked on the simplicity of The Shop Around the Corner. This is true in a technical sense. There are no trick angles, long shots, travelings, flashbacks, elaborate sets. The story was filmed sequentially in less than a month. In an interview in the New York Sun, Lubitsch called it “a quiet little story that seemed to have some charm.” His remark alludes to the comical, error-ridden romance between two shop employees. But there is a second storyline, less discussed, whose protagonist is Matuschek (Frank Morgan), the owner of the shop. If one watches through his eyes, one sees a different movie than the romantic comedy that it’s universally taken to be. From this perspective, there is nothing funny or romantic about the film. Pauline Kael distinguished between the plays and the screenplays of Samson Raphaelson, who wrote the script, by noting that the former are not lighthearted: “They aspired to be more than comedies; there was always a serious kernel.” His screenplay for The Shop Around the Corner is an exception to Kael’s rule, for the Matuschek material contains a kernel of seriousness buried inside a comedy.