Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Sunday Poem

What is Offered

This morning’s counteroffer:

one dead baby snapping turtle,

more tail, nearly, than shell

with one eye missing

in trade for the hangover

from last night’s dream –

the one about your brother

and how he faked his death.

Nothing fake about the turtle’s

but still, you cradle it in the hollow

at the center of your hand, carrying

it to the muddy edge, turning

the one eye toward the water.

Oh, let that one eye looking

see where to go from here,

tail like a rudder,

head swinging side to side

death coming into view –

then the purple asters

bent over and frayed.

by Alexandra Risley Schroeder

from Ecotheo Review

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, January 10, 2025

What Car Crashes Reveal About Human Hubris and Fragility

Sara Mitchell at Literary Hub:

Crumple zones are a standard safety feature in modern vehicles. Upon impact, your car is designed to crush, mangle, and deform itself in a controlled manner. It absorbs the energy of the crash upon itself, rather than transferring the energy into what’s referred to as “the safety cell,” aka you. Béla Barényi, dubbed by Mercedes Benz as “the lifesaver,” engineered the first crumple zones on an automobile. Mercedes said at the time, “Manufacturers carefully avoided using the term [safety]…nobody wanted to be reminded about the dangers of driving. The topic was viewed as a sales killer.”

Crumple zones are a standard safety feature in modern vehicles. Upon impact, your car is designed to crush, mangle, and deform itself in a controlled manner. It absorbs the energy of the crash upon itself, rather than transferring the energy into what’s referred to as “the safety cell,” aka you. Béla Barényi, dubbed by Mercedes Benz as “the lifesaver,” engineered the first crumple zones on an automobile. Mercedes said at the time, “Manufacturers carefully avoided using the term [safety]…nobody wanted to be reminded about the dangers of driving. The topic was viewed as a sales killer.”

But Barényi was ahead of his time when he recognized that the kinetic energy of a crash could be dissipated by the controlled deformation of the vehicle. That it would buy the two most important things needed: time and space between you and your crash. It buys fractions of a second as the hood crumples, before the most dangerous part, when the car stops and your head flies forward and back again. If you’re lucky, you’ll sprain your neck, but if you’re not, you’ll break it, or suffer what’s called a basilar fracture, a break at the base of the skull.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why sabre-toothed animals evolved again and again

Chris Simms in New Scientist:

Sabre teeth have very specific characteristics: they are exceptionally long, sharp canines that tend to be slightly flattened and curved, rather than rounded. Such teeth have independently evolved in different groups of mammals at least five times, and fossils of sabre-tooth predators have been found in North and South America, Europe and Asia.

Sabre teeth have very specific characteristics: they are exceptionally long, sharp canines that tend to be slightly flattened and curved, rather than rounded. Such teeth have independently evolved in different groups of mammals at least five times, and fossils of sabre-tooth predators have been found in North and South America, Europe and Asia.

The teeth are first known to have appeared some 270 million years ago, in mammal-like reptiles called gorgonopsids. Another example is Thylacosmilus, which died out about 2.5 million years ago and was most closely related to marsupials. Sabre teeth were last seen in Smilodon, often called sabre-toothed tigers, which existed until about 10,000 years ago.

To investigate why these teeth kept re-evolving, Tahlia Pollock at the University of Bristol, UK, and her colleagues looked at the canines of 95 carnivorous mammal species, including 25 sabre-toothed ones.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sean Carroll talks about himself, physics, the world

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The politics of German anti-anti-Semitism

Wolfgang Streeck at the European Journal of Social Theory:

Accessing and explicating the complexities of the collective subconscious that underlies a culture requires a hermeneutic skill and a richness of concepts and examples that is not at my disposal. I have nothing to add to Heidrun Friese’s insightful psycho-analysis of the Tätervolk that wants to draw a Schlussstrich by insisting that it doesn’t want to draw a Schlussstrich, offering reparation, Wiedergutmachung, for what cannot be repaired, hoping to be forgiven the unforgivable by declaring it unforgivable. I will instead focus on a simpler subject, one that lends itself, I hope, to be treated with the less sophisticated toolkit of the political scientist: not the depths of culture but the heights of politics, of government, of state, in particular the contingencies and constraints faced by a German state which had chosen to be the successor state of the Drittes Reich, in its dual relationship with its international context and its domestic society.

When the Federal Republic was founded by the three Western Allies in 1949, its first Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, had to govern with what the unconditional surrender had left of the Nazi killing machine. There was hardly anybody else, on both the conservative and the social-democratic side, who knew how to run a ministry, a secret service, a police corps, a court of justice, or injustice as the case might have been.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

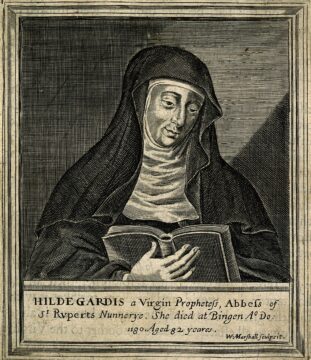

Hildegard of Bingen’s Prophetic Enchanted Ecology

Maria Popova at Marginalia:

At seventy-six, Hildegard of Bingen — poet, painter, healer, composer, philosopher, mystic, medical writer — has just finished writing and illustrating her third and farthest-seeing book: The Book of Divine Works, chronicling seven years of prophetic visions. God had first begun speaking to her in “the voice of the Living Light” when she was three, but she never suffered the hubris of a self-appointed prophet — rather, she considered herself “a totally uneducated human being,” a “wretched and fragile creature,” who is merely a channel for divine wisdom. She may be the Western world’s first great crusader against dualism — in the sermons she delivered to priests, bishops, abbots, and ordinary people all over present-day Germany and Switzerland, she preached that “God is Reason,” that “Reason is the root” from which “the resounding Word blooms,” but also that “from the heart comes healing,” that we apprehend the world and its wisdom most clearly through the intuitions of the “inner eye” and “inner ear.”

Hildegard was fifty-six when she began receiving the vision that would become her Book of Divine Works. On its pages, between writings about birds and trees and stones and stars, between reckonings with the nature of eternity and the fundaments of love, she conceptualizes something the word for which would not be coined for another seven centuries: ecology.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Voice of the Blood (Hildegard von Bingen)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Is Civil Commitment Rehabilitating Sex Offenders—Or Punishing Them?

Jordan Michael Smith at Harper’s Magazine:

On Taisa Carvalho Mick’s first day as a psychotherapist with Larned State Hospital’s Sexual Predator Treatment Program (SPTP), her co-workers warned her to be careful around her patients. She shouldn’t get close to them or believe a word they said, other staffers told her. They were untrustworthy predators, liable to manipulate her—or worse. Mick was suprised. She didn’t hear anything about empathy or treating patients with respect, even though the ostensible goal of the program was to provide therapy.

Larned, Kansas, is a city of 3,700 people surrounded by wheat fields and cattle farms. Like nineteen other states, the District of Columbia, and the federal government, Kansas detains many former inmates convicted of sex offenses after they finish serving their criminal sentences. They remain confined in treatment facilities until an evaluator deems them unlikely to reoffend and a judge agrees to their release. Supporters of this practice, which is called civil commitment, defend it as a form of medical treatment necessary for public safety. The handbook provided to those detained at Larned puts it this way: “It is the vision of the SPTP to provide residents with the knowledge and tools needed for their reintegration back into society.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

What Matters More for Longevity: Genes or Lifestyle?

Dana Smith in The New York Times:

When Dr. Nir Barzilai met the 100-year-old Helen Reichert, she was smoking a cigarette. Dr. Barzilai, the director of the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, recalled Mrs. Reichert saying that doctors had repeatedly told her to quit. But those doctors had all died, Mrs. Reichert noted, and she hadn’t. Mrs. Reichert lived almost another decade before passing away in 2011.

When Dr. Nir Barzilai met the 100-year-old Helen Reichert, she was smoking a cigarette. Dr. Barzilai, the director of the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, recalled Mrs. Reichert saying that doctors had repeatedly told her to quit. But those doctors had all died, Mrs. Reichert noted, and she hadn’t. Mrs. Reichert lived almost another decade before passing away in 2011.

There are countless stories about people who reach 100, and their daily habits sometimes flout conventional advice on diet, exercise, and alcohol and tobacco use. Yet decades of research shows that ignoring this advice can negatively affect most people’s health and cut their lives short. So how much of a person’s longevity can be attributed to lifestyle choices and how much is just luck — or lucky genetics? It depends on how long you’re hoping to live. Research suggests that making it to 80 or even 90 is largely in our control. “There’s very clear evidence that for the general population, living a healthy lifestyle” does extend the life span, said Dr. Sofiya Milman, a professor of medicine and genetics at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How To Use Your Body To Make Yourself Happier

Janice Kaplan in Time Magazine:

If your goal is to be happier in the year ahead, you might focus on your body rather than your mind. You can start right now by sitting up a little straighter. Then give a brief smile—even a fake one. These tweaks will tell your brain that something good is about to happen and you’re more likely to feel positive and upbeat.

If your goal is to be happier in the year ahead, you might focus on your body rather than your mind. You can start right now by sitting up a little straighter. Then give a brief smile—even a fake one. These tweaks will tell your brain that something good is about to happen and you’re more likely to feel positive and upbeat.

Sound unlikely? In research led by cognitive scientist John Bargh at Yale in 2009, people who held a cup of warm cup coffee before an interview were more likely to find an individual warm and kind. A 2010 study led by psychologist Joshua Ackerman, showed that people make different decisions when they’re seated in a hard chair versus a soft one. Soft seat, soft heart, you might say. When asked to negotiate to buy a new car, those in the hard chairs offered dramatically less than the others after one offer was rejected. Hard chairs made people harder negotiators.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

The Fire Burns

When you find human society disagreeable

and feel yourself justified in flying to solitude,

you can be so constituted as to be unable

to bear the depression of it for any length of time,

which will probably be the case if you are young.

Let me advise you, then, to form the habit of taking

some of your solitude with you into society,

to learn to be to some extent alone

even though you are in company;

not to say at once what you think, and, on the other hand,

not to attach too precise a meaning to what others say;

rather, not to expect much of them, either morally or intellectually,

and to strengthen yourself in the feeling of indifference

to their opinion, which is the surest way of always

practicing a praiseworthy toleration.

If you do that, you will not live so much with other people,

though you may appear to move amongst them:

your relation to them will be of a purely objective character.

This precaution will keep you from too close contact with society,

and therefore secure you against being contaminated

or even outraged by it.

Society is in this respect like a fire

—the wise man warming himself at a proper distance from it;

not coming too close, like the fool, who, on getting scorched,

runs away and shivers in solitude, loud in his complaint

that the fire burns.

by Arthur Schopenhauer,

From Essays and Aphorisms

Poetic Outlaws

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, January 9, 2025

The self-serving myths of a new wave of defense tech

Sophia Goodfriend in the Boston Review:

The unending wars and fortified borders fracturing much of the world have created lucrative testing grounds for the private firms tinkering with defense and security technologies. Venture capitalists scrolling through pitch decks of products seemingly lifted from blockbuster thrillers are rapidly cashing in. According to a Dealroom report released in late September, investment in defense tech startups is up 300 percent since 2019 in NATO countries; funders injected $3.9 billion dollars into the industry just this year. International relations experts Michael Brenes and William Hartung say we are on the verge of “a profit-driven rush toward a dangerous new technological arms race.” But it is more like a crowd crush—one that’s been ramping up insecurity across most of the world for a while now.

The unending wars and fortified borders fracturing much of the world have created lucrative testing grounds for the private firms tinkering with defense and security technologies. Venture capitalists scrolling through pitch decks of products seemingly lifted from blockbuster thrillers are rapidly cashing in. According to a Dealroom report released in late September, investment in defense tech startups is up 300 percent since 2019 in NATO countries; funders injected $3.9 billion dollars into the industry just this year. International relations experts Michael Brenes and William Hartung say we are on the verge of “a profit-driven rush toward a dangerous new technological arms race.” But it is more like a crowd crush—one that’s been ramping up insecurity across most of the world for a while now.

Petra Molnar’s new book The Walls Have Eyes: Surviving Migration in the Age of Artificial Intelligence offers an expansive account of how this global arms race is intensifying already violent homeland security and border regimes.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why Do Some People Thrive on So Little Sleep?

Marla Broadfoot in Smithsonian Magazine:

![]() Everyone has heard that it’s vital to get seven to nine hours of sleep a night, a recommendation repeated so often it has become gospel. Get anything less, and you are more likely to suffer from poor health in the short and long term—memory problems, metabolic issues, depression, dementia, heart disease, a weakened immune system.

Everyone has heard that it’s vital to get seven to nine hours of sleep a night, a recommendation repeated so often it has become gospel. Get anything less, and you are more likely to suffer from poor health in the short and long term—memory problems, metabolic issues, depression, dementia, heart disease, a weakened immune system.

But in recent years, scientists have discovered a rare breed who consistently get little shut-eye and are no worse for wear.

Natural short sleepers, as they are called, are genetically wired to need only four to six hours of sleep a night. These outliers suggest that quality, not quantity, is what matters. If scientists could figure out what these people do differently it might, they hope, provide insight into sleep’s very nature.

“The bottom line is, we don’t understand what sleep is, let alone what it’s for. That’s pretty incredible, given that the average person sleeps a third of their lives,” says Louis Ptáček, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

François Chollet: “AI o-models are far beyond classical Deep Learning”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Four years later

Matthew Yglesias at Slow Boring:

The scariest thing about contemporary American politics is that on January 7, 2021, it was widely acknowledged among American conservatives that Donald Trump’s behavior on January 6th was completely unacceptable.

The scariest thing about contemporary American politics is that on January 7, 2021, it was widely acknowledged among American conservatives that Donald Trump’s behavior on January 6th was completely unacceptable.

No one, at the time, was emotionally or intellectually invested in debating whether it was “really” a coup or whether a political movement that did something like that was “really” fascist. Mitch McConnell said Trump was morally responsible for the crimes committed. Steve Schwarzman called it “appalling and an affront to the democratic values we hold dear as Americans.” Kevin Williamson of National Review rightly called the riot at the Capitol “just the tip of a very dangerous spear.”

I’m not surprised or even particularly upset that so many people who acknowledged the gravity of the offense at the time ended up voting for and supporting Trump.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Crisis & Christian Humanism with Alan Jacobs

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

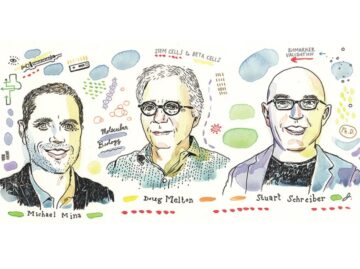

Where the Grass Is Greener: Leaving academia to advance biomedical research

Jonathan Shaw in Harvard Magazine:

Not infrequently, companies lure professors to highly paid positions directing scientific research in pharmaceuticals, technology, and related fields. But the recent departures of some leading Harvard scientists deeply committed to improving human health point to a different phenomenon: challenges to conducting translational life-sciences research in academic settings. Given the University’s emphasis on and investment in the life sciences and biomedical discovery, these scientists’ differing decisions suggest emerging issues and concerns about current constraints and the future of such research.

Not infrequently, companies lure professors to highly paid positions directing scientific research in pharmaceuticals, technology, and related fields. But the recent departures of some leading Harvard scientists deeply committed to improving human health point to a different phenomenon: challenges to conducting translational life-sciences research in academic settings. Given the University’s emphasis on and investment in the life sciences and biomedical discovery, these scientists’ differing decisions suggest emerging issues and concerns about current constraints and the future of such research.

Applying for National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants can take a substantial portion of an investigator’s time, and as much as a year can pass between a submission deadline and the point when funds are received and disbursed by the recipient’s home institution.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why kids need to take more risks: science reveals the benefits of wild, free play

Julian Nowogrodzki in Nature:

Over the past two decades, research has emerged showing that opportunities for risky play are crucial for healthy physical, mental and emotional development. Children need these opportunities to develop spatial awareness, coordination, tolerance of uncertainty and confidence.

Over the past two decades, research has emerged showing that opportunities for risky play are crucial for healthy physical, mental and emotional development. Children need these opportunities to develop spatial awareness, coordination, tolerance of uncertainty and confidence.

Despite this, in many nations risky play is now more restricted than ever, thanks to misconceptions about risk and a general undervaluing of its benefits. Research shows that children know more about their own abilities than adults might think, and some environments designed for risky play point the way forwards. Many researchers think that there’s more to learn about the benefits, but because play is inherently free-form, it has been logistically difficult to study. Now, scientists are using innovative approaches, including virtual reality, to probe the benefits of risky play, and how to promote it.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Auden’s Island

Alan Jacobs at The Hedgehog Review:

When, on January 19, 1939, W.H. Auden boarded at Southampton a ship bound for New York City, he could not have known that he would never live in England again. But some months earlier, he had told his friend Christopher Isherwood that he wanted to settle permanently in the United States. Almost as soon as he arrived in New York, he began to rethink his calling as a poet, and, moreover, to reconsider the social role and function of poetry. (He also began a spiritual pilgrimage that would lead him to embrace the Christian faith of his childhood.)

When, on January 19, 1939, W.H. Auden boarded at Southampton a ship bound for New York City, he could not have known that he would never live in England again. But some months earlier, he had told his friend Christopher Isherwood that he wanted to settle permanently in the United States. Almost as soon as he arrived in New York, he began to rethink his calling as a poet, and, moreover, to reconsider the social role and function of poetry. (He also began a spiritual pilgrimage that would lead him to embrace the Christian faith of his childhood.)

His work of this period combined a proclamation of the value of microcultures with a commitment to an intellectual cosmopolitanism. He celebrated the “local understanding” achieved in the informal salon run by a German émigré, Elizabeth Mayer, from her home on Long Island, but what bound the members of that salon to one another was the combination of cultural and national diversity with moral sympathy. In a poem composed immediately after the Nazis invaded Poland in September 1939, he wrote:

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages….

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.